|

Our group meets on the first Friday of every month at 6:30 p.m. at Saint Anthony's Wellness Center in the Alton Square Mall. For driving directions call the Wellness Center at 462-2222. We encourage all members to attend the DSAGSL Annual Conference on Saturday, March 9th.

Just over one year ago, the State of Illinois substantially revised its Early Intervention guidelines - the guidelines which determine the nature and number of early intervention services that the State will provide to children with disabilities under the age of 3. These guidelines are now undergoing revisions. Both the original guidelines and proposed revisions are available on-line at: http://www.state.il.us/agency/dhs/earlyint/ earlyint.html.

In this issue we reprint elements of a relevant exchange between Dr. E. Duff Wrobbel, a parent of a child with Down syndrome and member of our parent support group, and Dr. Stanley I. Greenspan, of Bethesda, MD, principle author of the Interdisciplinary Council on Developmental and Learning Disorders Clinical Practice Guidelines regarding the Illinois State Early Intervention Program's diagnosis-specific guidelines for a the 6 hour therapy cap for Down syndrome. Dr. Greenspan's work is cited by the State of Illinois E.I. program as the basis for its service guidelines.

Enclosed is a brochure for a conference to be held on March 12 at Pere Marquette. The conference is free to individuals with disabilities, their family members and/or caregivers. For more information, contact Vickie Wilson at VickieEWilson@aol.com or toll free (877) 550-8274.

STARNet Region IV

April 6, 9:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. STARNet Region IV Family Conference. This daylong conference will consist of two major strands: Assistive Technology and Behavior. $10 single; $15 couple - includes lunch. Location: Keller Center, Effingham. Contact: Sharon Gage, 397-8930, ext. 169.

|

|

Regional Events

February 21 or March 11, 7:00 p.m. Planning for the Future of Your Child with Special Needs. Issues that will be addressed in this workshop: Government Benefit Eligibility; Guardianship and Conservatorship/Guardian Ad Litem; Financial Security and Funding Options. Location: Special Children, Inc. 1306 Wabash Avenue, Belleville, IL 62220. 90 minutes presentation followed by questions and answers, by MetDESK Specialist Richard Butler, New England Financial Group, #4 CityPlace Drive, Suite 150, St. Louis, MO 63141. (314) 567-6667. RSVP: Bobbie Bass (618) 234-6876.

March 9. The Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis Annual Conference at the Hyatt Regency, St. Louis, One St. Louis Union Station, St. Louis, MO 63103. Cost for the conference is $20 per person registered before March 1, 2002, $30 per person after March 1. Registration includes a buffet lunch.

Parent/Professional Conference Schedule

8:30 - 9:00 Registration, Coffee

9:00 - 10:30 Keynote: Dr. Phil M. Ferguson, Lessons from Life: Thinking about Adulthood for People with Intellectual Disabilities

10:30-10:45 Break

10:45-11:45 Parent Panel Discussion

11:45- 12:15 Self Advocates Presentation

12:15 - 1:30 Lunch

1:30 - 2:45 Concurrent Session 1

Your Story - how to communicate your child and family story, Jean Haase and Ann Stackle

It Hurts, I'm Scared. Preparing children for medical, dental and other scary appointments, Bev Fields R.N., Vicki McMullin, Ph.D.

Communication Ages 0-12, Timothy Sachs

Teaching Reading to Children with Down Syndrome - Preschool and Elementary, Patricia Oelwein

Promoting Self-Esteem in Persons with Down Syndrome, Dennis McGuire, Ph.D.

Nutrition For Children with Down Syndrome - Ages 0-10, Barbara Linneman, M.S., R.D., L.D.

2:45 - 3:00 Break

|

moonlight is the newsletter of the Riverbend Down Syndrome Association. It is made possible by the William M. BeDell Achievement and Resource Center, 400 South Main, Wood River, IL 62095, (618) 251-2175.

Editor: Victor Bishop

Web Site: http://www.riverbendds.org/

|

|

3:00 - 4:15 Concurrent Session 2

Communication Ages 12-18, Deborah Hadley and Margo Andrich

Teaching Math to Children with Down Syndrome - Preschool and Elementary, Patricia Oelwein

Promoting Self-Esteem in Persons with Down Syndrome, Dennis McGuire, Ph.D.

Weight Management for Persons with Down Syndrome - Ages 0-10, Barbara Linneman, M.S. R.D., L.D.

Early Intervention/Early Childhood Ages 0-3, Kate Hannon, Program Director, Belle Center Staff

For the third year we are having a conference for teens and adults with Down syndrome that occurs concurrently with an educational conference for Parents and Professionals. The conference is open to teens and adults with Down syndrome ages 16 and older. Registration is limited to 25.

Teen & Adult Conference Schedule

8:30 - 9:00 Registration

9:00 - 10:30 Open Art Studio

Under the direction of Paulette Tillelry and Angel Weber participants will be able to tap into their creative Nature with a variety of mediums such as acrylics, modeling clay, pastels and others. They will have the freedom to choose between projects of their choice and will be able to do as many projects as time will allow.

10:30-10:45 Break

10:45-11:45 Music Sectional

11:45 - 12:15 Join Parent/Professional Conference for self advocates presentation

12:15 - 1:30 Lunch

1:30 - 2:45 Improvisational Theatre Workshop

Ed Reggi will lead the group in Improvisational Theatre. Through dramatic play participants can increase their verbal and language skills; spontaneously think and create; play freely with rules, organization and structure; build personal character and confidence; encourage a dialogue in small and large groups; explore their world using physical movement and have lots of fun with drama!

2:45 - 3:00 Break

3:00 - 4:15 Dancing Sectional with Heidi Morgan

Get ready to move as Heidi Morgan, teacher at University City High School, teaches current dances including popular line dances.

For a conference registration brochure call Lydia at the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis office (314) 961-2504, DSAGSL@msn.com or Karen Kramer (636) 227-2105, Kkramer2@swbell.net.

March 12, 9:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Promoting Health in Adults with Developmental Disabilities. This seminar is sponsored by the Arc of Illinois and will focus on the physical and mental health of persons with developmental disabilities, including diet, exercise, sleep and social opportunities. Medical and psychosocial problems seen in adults with developmental disabilities will be discussed. Additional focus will be placed on the unique health issues of older women with intellectual disabilities. Presenters: Brian Chicoine, M.D.: Medical Director and co-founder of the Adult Down Syndrome Center of the Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, IL. This Center has served and documented the health and psychosocial needs of over 1400 adults with Down syndrome since its inception in 1992. Carol J. Gill, Ph.D.: Clinical and research psychologist specializing in health and disability and Assistant Professor of Human Development at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Dennis McGuire, Ph.D.: Director of Psychosocial Services for the Adult Down Syndrome Center of the Lutheran General Hospital. He has an appointment as a Clinical Assistant Professor with the Institute on Disability and Human Development of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Location: Holiday Inn Hotel & Conference Center, 7800 Kingery Highway, Willowbrook, IL 60521. (630) 325-6400. For registration information call Janet at (708) 206-1930.

Down Syndrome Articles

Following is the text of the letter from Dr. Wrobbel to Dr. Greenspan:

Dear Sir:

I am the parent of a child with Down syndrome and a resident of the State of Illinois. Just recently, our state's Early Intervention program was substantially revised. One of the major changes was the institution of diagnosis-specific guidelines for the number of therapy sessions children could receive without challenge. Below is the exact text of the guidelines for Down syndrome from Illinois Prop 502:

"Down Syndrome: Down Syndrome is a condition which usually affects cognition. Not all children with Down Syndrome require specific OT and PT therapy. All children with Down Syndrome will benefit from a PT evaluation to develop a home program for positioning and handling because of the underlying hypotonia. Acceptable frequency of PT is from an evaluation once every three months to once weekly. Activities involving cervical flexion/extension are contraindicated. OT to foster self-care skills and exploratory play is often helpful. The usual range is from evaluation every three months to once weekly therapy. Feeding evaluation and ongoing feeding therapy weekly is appropriate for children who have oral motor/feeding dysfunction. Communication/Speech-Language evaluation for children with Down Syndrome may be appropriate; the usual frequency is from evaluation once every three months to once weekly. Most children with Down Syndrome will require 6 or less combined therapy sessions monthly. A total of more than 6 combined therapy sessions monthly will require further justification."

When I contacted the Illinois State Department of Human Services for information concerning the rationale for the 6-hour cap, they referred me to your ICDLC Practice Guidelines. However, when I read these guidelines, I not only do not see any specific guidelines for the appropriate number of allowable therapy session per diagnosis, this seems to me to actually contradict much of what I read. However, I must admit that my doctorate is in Speech Communication, so I am well outside my area of expertise here. Would you kindly contact me at the above address with a clarification on this point? I appreciate your help.

Sincerely,

E. Duff Wrobbel, Ph.D.

Dr. Greenspan's reply was two part. The first a letter, the unedited text of which follows:

Dear Dr. Wrobbel:

Although it's been some time since you wrote asking for clarification of our ICDL Guidelines regarding therapy sessions for a child with Down syndrome, I wanted to get back to you in the hope that my answer would be useful to you.

We suggest that the services in therapy and educational programs for specific programs be determined by that child's unique developmental profile. Frequency should be determined by a profile of the child's needs and not limited by specific diagnostic groupings.

With all best wishes,

Sincerely,

Stanley I. Greenspan, M.D.

The second part of Dr. Greenspan's reply came in a telephone exchange on February 11, 2002 in which Dr. Greenspan gave Dr. Wrobbel permission to cite the above letter, but also suggested referring specifically to the ICDL Clinical Practice Guidelines themselves, parts of which are cited below:

"Increasing numbers of young children are presenting with non-progressive developmental disorders involving compromises in the capacities of relating, communicating, and thinking. These developmental disorders include autistic spectrum disorders, multi-system developmental disorders, cognitive deficits, severe language problems, types of cerebral palsy, and others. They involve many different areas of developmental functioning, ranging from planning motor actions and comprehending sounds to generating ideas and reflecting on feelings. New research and clinical observations are making it possible to more fully identify these different capacities and, thereby, characterize each child and family according to their unique profile of functional developmental capacities. These new observations also make it possible to subdivide complex developmental disorders, such as autism, based on different configurations of functional or dimensional processes (e.g., auditory processing, motor planning, and reciprocal, affective interactions). Most important, they enable clinicians to individualize assessment and intervention approaches in response to the child-and-family-specific question: "What is the best approach for a given child and family?" Answering the child-and-family-specific question makes it possible for clinicians to tailor the approach to the child, rather than fit the child to the program. Too often, however, the clinical practice is to fit the child to a standard program. The rationale for fitting the child to the program is, in part, driven by theory and belief (e.g., all children with autism should receive a specific approach, regardless of their individual developmental profiles). It is also driven by the mistaken assumption that children who share a diagnosis because they display some similar symptoms also have a similar central nervous system processing profile and under-lying neurobiology."

"The ICDL Clinical Practice Guidelines is unique in three ways. First, the guidelines go beyond syndrome-based approaches and build on emerging knowledge of different functional developmental patterns within broad syndromes, such as autism. This specificity enables the identification of each child and family's unique developmental profile, including strengths and vulnerabilities, and the development of an individualized intervention plan that works with all the relevant functional developmental and processing capacities. Second, The ICDL Clinical Practice Guidelines addresses a level of clinical complexity, detail, and depth not often attempted with such efforts. The guidelines recognize the need to go further than simply documenting, in broad strokes, the value of interventions such as special education, social skills training, and/or communication and speech and language therapy. The guidelines recognize that there is enormous variation in clinical goals, techniques, and therapist/child interactions within similarly named interventions (e.g., speech and language therapy), based on the individual challenges of a particular child and family and on the practitioner's personality, training, skill level, and interactive patterns with a particular child and family. The guidelines, therefore, attempt to describe specific strategies and interaction patterns for the different functional areas: For example, how to work with a child who is very over-reactive to touch, under-reactive to sound, has poor motor-planning skills, is very avoidant, and moves away from adults and other children to help him learn to enjoy care-giver and peer relationships, interact, communicate, and problem solve. This type of child-specific clinical work requires enormous clinical skills. These skills, which will often determine the success of the overall intervention program, can only be captured by in-depth clinical descriptions that go significantly beyond the identification of a generic intervention category. Elaborating upon and systematizing in-depth clinical strategies to guide intervention efforts require a broad knowledge base supported by both research and clinical experience. The third unique feature of The ICDL Clinical Practice Guidelines is that the guidelines are based on both current research and clinical experience (i.e., expert opinion) from all the disciplines that work with developmental problems. A number of organizations have issued, or are issuing, guidelines based predominantly on reviews of current research (or evidence). Although increasing research is an important long-term goal, the current research base is too incomplete to fully guide clinical decisions. It lacks the scope and specificity necessary to guide interventions tailored to the individual child and family's unique developmental profile."

"The ICDL Clinical Practice Guidelines further addresses how these functional developmental capacities become incorporated into the process of a comprehensive evaluation, the construction of the developmental profile, and the formulation of a child-and-family- specific comprehensive intervention program. The functional developmental approach serves as the basis for recommendations for changes in screening, assessment, and intervention services and local, state, and federal policies. As indicated in Chapter 1 of this volume, infants and children with non-progressive developmental and learning disorders evidence challenges as well as strengths in many different areas of functioning. Each of these areas must be worked with as part of a comprehensive assessment and intervention program. Such a comprehensive program involves a number of disciplines working together, guided by the unique developmental profile of the child and the child's family. Although seemingly self-evident, these basic tenets have been surprisingly difficult to put into practice. For many developmental and learning disorders, disagreement exists about what areas of functioning should be addressed, the best ways to observe and assess them, and the interventions most likely to be helpful. In addition, each child and family is quite unique, and each clinician, regardless of background and training, has a personal way of practicing his or her craft. These challenges are formidable, but dealing with them is necessary to creating an individualized interdisciplinary approach that tailors the program to the child rather than fits the child to the program."

The contradictions between the guidelines originally proposed by Dr. Greenspan and the ICDL and the 6-hour cap imposed by the State of Illinois are disturbing. Please consider contacting DHS Secretary Linda Reneé Baker at the Bureau of Early Intervention at DHSEI06@dhs.state.il.us, by telephone at (217) 782-1981, or by mail at:

Bureau of Early Intervention

623 East Adams

Second Floor

P.O. Box 19429

Springfield, IL 62794

Now is the time to work together to have this cap removed for our children!

Smiles, tears for homecoming king. Students honor their classmate with Down syndrome by voting him the school crown by Nate Reens, Staff writer. The Holland Sentinel, September 29, 2001. Reprinted with the permission of Jan Timmermann, E-mail: jtimmermann@sentinelnet.com, Managing Editor, Holland Sentinel. © Copyright 2001 The Holland Sentinel.

Rob Sterken's face took on the glow of a stadium light Friday night even before he was carried off Municipal Stadium's field on the shoulders of two friends after a big victory.

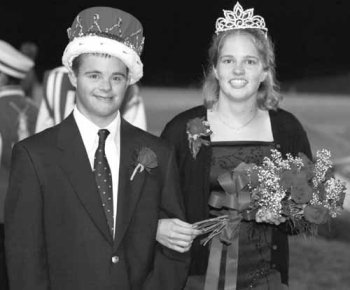

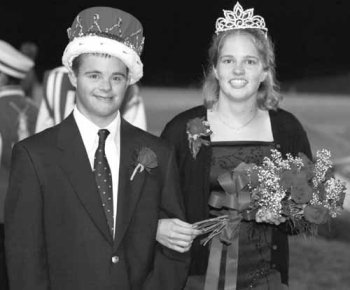

Sterken, a Holland High senior who has Down syndrome, didn't win the game with a touchdown or last-second field goal, but he was the winner of the school's homecoming crown.

The 19-year-old son of school board President Deb Sterken was happy enough just to be a member of the homecoming court. But when word came over the public address system - and the home crowd roared in approval - that he earned the title of king, Sterken, taken by surprise, clenched his fist in celebration and rushed to the risers to begin his reign with the queen, Megan Tripp.

"I'm really, really excited and surprised about it," said Sterken, clad in khaki trousers, blue sport jacket and matching blue tie with tiny University of Michigan emblems. "I thank all the people who voted for me. I think they're great."

|

| Holland High seniors Rob Sterken and Megan Tripp were crowned as the 2001 Homecoming King and Queen Friday night at Holland Municipal Stadium. Sentinel/J.R. Valderas |

Shortly after the win and the end of half-time activities, fellow king candidates Chris DeJong, a world-class swimmer, and Jonathan White, an accomplished vocalist, hoisted Sterken onto their shoulders and carried him away.

"We're so happy for Rob. We were all rooting for him and really pushing for him to be the king," White said. "Everybody wanted him to win because he is Mr. Holland High.

"People know Chris because of swimming and some know me because of music, but Rob is the one that deserves this honor."

In addition to his classes at the high school, Sterken volunteers as manager of the school's boys' varsity soccer team in the fall, boys' varsity basketball squad during the winter and wraps up his duties with the girls' varsity soccer squad come spring.

Sterken also is involved with a school work program which places him at Hope College's Dow Center in the mornings to learn various tasks behind running a physical education and sporting event facility.

Cindy Yonker, a former teacher of Sterken's, said people around the district appreciate all the senior has dedicated himself to and how he treats others.

"From the first grade, Rob made an impression on this whole group of kids. They wanted to be his friend," Yonker said as she sat with Deb Sterken and another former teacher, Kathy Zwiers. "He touches everyone who meets him in a positive way."

As tears welled in Deb Sterken's eyes and slowly dripped onto her jacket, the newly crowned king's mother was overcome by the generosity of her son's fellow students.

"I'm just so thrilled for Rob and I feel so blessed he's with this group of students," said Deb Sterken. "I think it's a real credit for the type of students we have here and a credit to our staff who let him grow into who he is."

Bob Sterken said he was surprised but not shocked upon learning of his son's accomplishment. The Sterkens were happy with Rob's nomination, but the win took on a special meaning.

"All three candidates are wonderful kids, but they're all different," Bob Sterken said. "Chris is a phenomenal athlete, Jonathan is incredibly gifted in the arts and Rob has strengths different from both. I think he's earned it."

Teacher Deb Boes said Sterken is deserving of the honor bestowed upon him by the school's student body.

"Rob is a great, great kid who's very dedicated to Holland High School," Boes said. "He's willing to do anything to help other students and staff members and is always very excited about learning."

The written word fosters the spoken one by Janet M. Krumm, e-mail: nhcjmk@nh.ultranet.com. The New Hampshire Challenge, Winter 1999. © Copyright. The New Hampshire Challenge, PO Box 579, Dover, NH 03820. URL: http://www.nhchallenge.org/. Reprinted with the expressed permission of the author.

The four children came into the small room crammed with books, toys, informational notices, and filing cabinets, ready to work. They had arrived at the Sarah Duffen Centre in Portsmouth, England an hour before with their parents, who had spent that time together with the staff catching up on the children's growing language and reading accomplishments in the Centre's playroom. What was working? What was not? What problems were encountered? What successes? The lesson plan for the day was distributed to each parent before they moved to the educational group room.

Eliot Barnett, age three years and seven months, folded himself into his father Simon's lap as they took their place at the child-sized table. Michaela Jackson, age three years and four months, looked around curiously at the several strangers in the room after she took her seat as her mother Mary pulled up a chair behind her. Conor Hayes, the oldest at four years and ten months, sat down and immediately busied himself with the toys he found on the table as his mother Debbie greeted the other parents, eventually finding her way near her son. Pip carried in Andrew, three years and nine months, helping him to get settled in his chair and then sat close by.

Several adults were seated in the back of the room - mostly students there to observe. Gillian Bird, the teacher of this group, entered, seated herself at the table and greeted everyone with a smile and a few friendly words. Without much preamble, she went to work.

First, she introduced vowel sounds using cards with pictures of eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, asking each child to touch the corresponding facial feature and say the word. Each spoken word was accompanied by a gesture made by both the child and the teacher. Parents were active participants in the lesson, reinforcing good answers and modeling when help was needed. Then, Bird asked each child in turn to pick out a puzzle piece with a picture of an animal of his or her own choice and say the name of the animal.

The lesson moved quickly to accommodate the short attention span of young children, with lots of praise and smiles to reinforce the work the children were doing. Number cards were introduced, with both numeral and word. The children were asked not only to say the number, but to physically count the correct amount of little people figures as they put them into a teapot.

For the next lesson, the children were asked to look at pictures of different fruits and pick out the one requested. The level of difficulty of each request was adapted to the ability of the particular child. For instance, Andrew was asked simply to identify a fruit of his choosing; Conor was asked to identify a picture showing the large or small fruit requested.

Then it was Michelle Whitcomb's turn to lead the group. The parents pulled out cards with the names of the children and their family members. Each child in turn was asked to pick out a name, read it and then match a duplicate card. Two weeks prior to this lesson, Michaela knew only her own name. For this lesson she picked out and read the names of her two brothers, Christopher and Simon. Both Michelle and Michaela's mother Mary sang her praises at this accomplishment.

After about an hour of work the group disbanded, and Eliot, Michaela, Andrew and Conor and their parents left for home, their folders full with name cards and the lesson plan of the day. Educational group time at the Sarah Duffen Centre was over, but their work would continue at home, ten to fifteen minutes a day, child and parent working together.

This scenario is played out every Tuesday at the Sarah Duffen Centre, with each age group meeting at a two-week interval. What makes this preschool group situation unique is that each of the four children eagerly working on language skills has Down syndrome. In fact, all the children who come to the Sarah Duffen Centre have Down syndrome. They come to improve their language skills. To do that, they learn to read.

The professionals who work at the Sarah Duffen Centre have taken a distinctive approach to improving the language skills of children with Down syndrome. The Centre is the home of The Down Syndrome Educational Trust, founded by Sue Buckley, psychologist and Professor of Developmental Disability who directs the Centre for Disability Studies at the Department of Psychology at the University of Portsmouth.

Nearly twenty years ago, Buckley became intrigued by the account of Leslie Duffen, who attributed his daughter Sarah's unusually developed language skills to the fact that he had taught her to read starting at three years of age. Leslie Duffen wrote Buckley a letter, outlining his then twelve-year-old daughter's remarkable progress. She was enrolled in a local comprehensive school and was reading and writing better than most children with Down syndrome. Leslie was hoping to find a psychologist who would do research with a group of children to see if his approach could benefit other children.

Buckley was intrigued, both professionally and personally - she had an adopted daughter with Down syndrome. She began to scour research studies to see if she could find anything that might explain Sarah's progress. The studies she found indicated that visual memory in children with Down syndrome was stronger than auditory memory. This convinced her that researching reading as a method of improving language development was important. She was granted funding (with the help of Leslie Duffen) which eventually led to the development of the program now housed at the Centre named after Sarah.

What Buckley and the others who work at the Centre have learned over the last two decades is that reading improves language skills. And that children with Down syndrome as young as two years old can be taught to read.

What gives their work credibility comes not only from the accounts of the parents, but the research that has been done by the Trust in partnership with the University of Portsmouth. In fact, one of their guiding principles is that: "All interventions shall be scientifically evaluated and clear evidence of outcomes, advantages and disadvantages be provided to parents." All research, the Trust declares, "will be conducted and disseminated to a standard acceptable to the international scientific community."

Never too early to start

When Edward Stoner was born a little over two years ago, his family was living abroad. Sioban, his mother, began using the internet to get information and found The Down Syndrome Educational (DownsEd) Trust. She contacted them and was sent books and articles explaining how she could teach her child. Sioban started using teaching materials from the Centre when Edward was eighteen months old.

When they moved back to the United Kingdom, Sioban was invited to bring Edward to the Centre for reading instruction. Sioban's first reaction was that Edward was too young. After all, he was not yet two years old! But she did accept an invitation to attend an open house. There she saw other young children Edward's age learning to read, leading her to change her mind about her son's readiness.

At the time of the interview, Edward had been reading for two weeks. His developmental evaluation was close to the norm, Sioban reported. He read and spoke the names of each member of his family, with the exception of his brother James. When Edward read James' name, he signed.

What is clearly evident at the Sarah Duffen Centre is the central role parents play in instruction. "The children who have done best have a great deal of home input," Buckley explained. Recognizing that fact, the Centre concentrates on teaching parents how to teach their children. Because the children come once every two weeks, progress depends on the work parents do with them every day. Centre staff give parents the tools, but they also give more. "You need to give parents hope, a sense of direction and support," Buckley stated.

Children in England enter school at age 4 and, as in the United States, parents must advocate strongly to get their children included in a comprehensive school rather than sent to a special school. A process similar to the IEP process exists, but the members of the "team" work quite independently of each other. Staff at the Sarah Duffen Centre will assist parents by providing information and assisting them to advocate for an inclusive placement. Once a child is enrolled in a comprehensive school, the staff will also provide ongoing technical assistance to that school.

"We're getting much better at inclusion," Buckley said. However, she added: "Don't think we have it all together here in the U.K.. What we have is a strong network for the converted."

Studies yield good conclusions

Nearly twenty years of work and research have led Buckley and the staff at the Centre to the following conclusions:

- Most children with Down syndrome can learn to read and will be able to read and write to a level that is both useful and enjoyable.

- Reading instruction will improve the children's speech, language and memory development.

- Reading instruction will improve the children's scores on standardized tests and lead them to being assessed as brighter.

What has happened to the first children taught twenty years ago? "Some of them we know quite a lot about; some we don't," Buckley admitted. "A number of people are in college courses (editor's note: Colleges, comparable to high schools in the States, take students from sixteen through nineteen years of age.) Some were reading more at five than (they are) at sixteen because the special schools simply didn't include literacy training."

Buckley is confident about the positive effects of inclusion for children with Down syndrome. "An appropriate program for the child is an age appropriate class," she stated. A growing body of research, much of it done at the Centre, debunks the old theory that children with Down syndrome cannot learn. Still, she will admit that learning for children with Down syndrome is not the same as for other typical children. "We will have children whose reading skills are at par at age eight or nine," Buckley explained, "but whose comprehension is weaker. At twelve or thirteen," she added, "it is hard to keep them age appropriate (with reading material)."

Centre offers wide range of services

While language development and literacy are the focus of the efforts at the Sarah Duffen Centre, behavior management is another concern. "Sensible behavior control" is important to success in school and other social experiences, Buckley maintained. "People are being too nice," she explained. "They don't realize they can be as demanding about behavior as with any other child." Buckley often is asked to present workshops in schools on behavior management, and the Centre provides information to parents and professionals on the topic.

In addition to the educational groups, the Centre offers workshops and conferences on a variety of subjects, both to parents and professionals. Topics include infant and child development, reading and writing, feeding and eating skills, social skills and behavior, early language development, and working effectively with the schools. Professionals are offered workshops on assessment; health, development and family support; teaching reading and supporting literacy development; meeting the educational needs of children with Down syndrome; and speech, language and communication development.

The Down Syndrome Educational Trust publishes and sells books, articles, videos, and teaching materials. For a list of materials, or to make a purchase (credit card purchases are recommended), contact:

DownsEd

The Sarah Duffen Centre

Southsea

Portsmouth

Hampshire PO5 1NA

England

Telephone: 011 44 1705 824261

Fax: 011 44 1705 824265

E-mail: enquiries@downsnet.org

Web Wanderings

Dr. Libby Kumin has undertaken a study of the factors that help make children's speech more understandable or make it difficult to understand. She needs information from families. To participate, you need to complete a short survey. It is hoped that the results will help us to develop effective treatment programs. The results of the study will be shared with families and speech language pathologists.

Father's Journal

Birthday Cake

On his fifth birthday my son ate cake.

On his fifth birthday my wife cried tears of joy.

On his fifth birthday a proud father was I.

On his fifth birthday my son chewed for the first time.

|

|

The few minutes that you take to complete this form will be a tremendous help in our efforts to better understand and treat speech problems for children with Down syndrome. The survey is [no longer] available on-line [...] Click on Speech Intelligibility Survey. The questionnaire can also be mailed to you.

Send your address to lkumin@loyola.edu or

Dr. Libby Kumin

Loyola College Columbia Graduate Center 7135

Minstrel Way Columbia, MD 21045