|

|

Starting with this issue, we will be reprinting excerpts from The Five Goodbyes. Mothering My Child with Down Syndrome.

One of my highlights of the 9 th World Down Syndrome Congress was Dr. Mobley's presentation, which sheds light on the nature of the verbal short-term memory impairment in DS due to long term potentiation. Children with DS have a mean digit span of 2 ( Memory Training for Children with Down Syndrome. DSRP 7(1): 25-33) and subvocal rehearsal strategies have not met with success ( Long-term maintenance of memory skills taught to children with Down's Syndrome. DSRP 3 (3): 103-109). To counteract this limited-capacity verbal short-term memory system ( Impaired verbal short-term memory in Down syndrome reflects a capacity limitation rather than atypically rapid forgetting. J Exp Child Psychol 91(1): 1-23) our guest commentator, Dr. Teresa Cody, with her biochemistry knowledge, examined new Ginkgo Biloba research, which increased the digit span of her 8-year-old son Neal, from 1 to 5.

We are proud to publish two very successful Down syndrome fund raising events hosted in Illinois.

Family Connection, Vol. III, Issue I, Jan-Mar 2007, p. 12. Reprinted with the permission of Tim Nienhaus.

The "Puttin' For Down Syndrome" golf tournament raised $2,500 for the Down Syndrome Association [of Greater St. Louis] and $2,500 for the Down Syndrome Center at St. Louis Children's Hospital. But the October event in Swansea, Ill., was priceless to a special group of kids who attended their own clinic during the tourney.

More than a dozen children and young adults with Down syndrome took part in the clinic, courtesy of golf pro Dan Polites with the Clinton Hills Golf Club. Along with memories of perfecting their signature swing, each player got to take home his or her own personalized golf club. Joan and John Kane of Godfrey cheered 16-year-old Joe as he pounded his ball with cutting precision. Their son is a natural. "He doesn't have many things he does that are just for him, not that many opportunities, especially athletically," says Joan.

"It doesn't matter what your capabilities are, how old you are, how big you are, whether you're male, female, young or old," says Polites. "The golf ball doesn't know who's hitting it."

|

|

The shared experience at Clinton Hills united these young players with every golfer who has ever swung a club for fun, sport or any form of emotional release. "I think it's good therapy for anger," says Lydia Orso, 28, the first person with Down syndrome to be employed by the Down Syndrome Association [of Greater St. Louis]. "Sometimes when I'm stressed and I can't think I can just take it out on this ball."

|

| Back row: Joe Kane, Lydia Orso, Nate Greenbaum, Scooter Goley. Middle row: Justin Cote, Kaitlyn Trower, Emily Kramer, Paula Mass. Front row: Zach Jones, Marcus Fenner, Emmanuel Bishop. |

Tim Nienhaus, whose son Alex turned 3 in December and has Down syndrome, hoped when he planned the event that it would do more than raise money. "I wanted to do something to bring the community together with kids with Down syndrome, to create more of an awareness of how neat these kids are and how neat their families are," he says. Alex had a heart defect and suffered breathing problems when he was born. He had surgery and spent more than a month at Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital beginning when he was a week old. He continues to be treated for pulmonary and swallowing problems and also has been seen by eye and renal specialists.

|

|

|

Tim believes the development of the DS Center at St. Louis Children's Hospital will be extremely beneficial to families dealing with multiple complications. "It's such a juggle to coordinate all those doctors' appointments and therapists. The center keeps things up to date and calls to remind you when it's time to have your thyroid tested." The Center's mission is to optimize the quality of life for children with Down syndrome and their families by offering comprehensive care in one setting. At least 1,000 families in the St. Louis area have children with Down syndrome, almost half of whom are treated at Children's.

Polites may have taught the golf clinic, but he concedes he learned quite a bit from his young pupils. "I think I get more out of this than they do," he says. "It helps you realize how well these kids have adapted and how terrific they are. This is an enlightening situation. I can't wait to do it again."

|

| Katie Stemmler, Jacob Lakin & Cassie Scott |

1st Annual Down Syndrome Bowling Tournament by Joy Stemmler

On October 22, 2006, we hosted our 1st Annual Down Syndrome Bowling Tournament in Jerseyville, IL. It was a great success and we donated our proceeds of over $5,000 to the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis.

I, Jenn Lakin, and our family members and friends got donations for door prizes or raffle baskets. There were two 50/50 drawings and two secessions, at 12:30 and 2:00. Each secession had 16 lanes and all lanes were sponsored at a cost of $100.00. The tournament was Scotch Doubles and each couple paid $20.00. Everyone was very generous in helping and cash donations were collected.

Not only was the tournament a great success, it was a lot of fun. We were able to get some other parents there that have children with DS and it was a great way to meet new parents and make friends.

We are planning another one next year, and look forward to have more parents and children there. My daughter Katie was such a social butterfly going around and playing with the adults there. Jacob Lakin, Cassie Scott, Kiley Langa, and Ryan Spangler were also present. That was the whole idea of the tournament, to get people to get to know our children and realize that they are just like other children.

If anyone would like to bowl or just come up and meet new parents and let the kids get to meet new friends, we would really love to have you come. You can contact us, Eric & Joy Stemmler or Harry & Jenn Lakin.

Local Events

March 10 from 8:30 - 4:15 p.m. Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis Family Conference, 30 Years of Building a Better Life. Clayton High School, #1 Mark Twain Circle, Clayton, MO 63105.

2007 Keynote Presenters: Greg Palmer & Ned Palmer: 9:00 - 10:30. Adventures From Harrods to Hooters. Greg and Ned Palmer, author and subject, respectively, of Adventures in the Mainstream: Coming of Age with Down Syndrome.

Stages Performing Arts Academy's Troupe Broadway. 10:45 - 11:00.

Denise Poston: 11:00 - 12:15. Individuals Control Funding: An Alternative to Current Practices.

For additional information, contact the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis at (314) 961-2504, E-Mail: dsagsl@msn.com.

Future Planning

Visioning? Say What? Say What? Future Planning in Plain English, Vol. 2, No. 7, July-August, 2005 by Alexandra Conroy, Future Planning for Families with Special Needs. Waddell & Reed, Inc., One Oak Hill Center, Westmont, IL 60559. (630) 789-0044. Fax: (630) 789-8005.

This publication is for information only. Before making any financial decisions, please consult your benefits specialist, financial advisor or attorney.

Since this is the last issue of summer, I am taking a break from brain-breaking discussions on the details of Social Security, Medicaid, the Ticket to Work and the like. Instead, I am going to introduce you to my program for special needs planning, which is really your program. Recently, we have heard a lot about 'consumer-driven' or 'self-directed' services. The terms refer to social services and supports, but they also pinpoint how I approach financial future planning. In this newsletter, I will refer to your child with special needs. While it is always to your advantage to begin planning when your family member with special challenges is a child, it is never too late to begin and I have begun working with a number of families when the family member is already an adult. My process, and also the first stage of the process, is called 'visioning.' After we take a look at that, we will run through the subsequent stages: input, fine-tuning, strategy, implementation and coaching. Throughout this process, I am in contact and cooperation with your special needs attorney and other professionals intrinsic to your child's future quality life.

What is Visioning?

Visioning is the focus of your first face-to-face meeting with me. In the vision meeting, you talk and I listen. Your responsibility is to paint your child's future for me-in vivid colors. Where does she want to live? What does he like doing? What kind of work does or might she do? Who are the significant people in his life and how will they be involved? The vision meeting sets the tone and the pace for our whole working relationship. For my part, I will explain how the financial future planning process works, what it costs, how long it takes. The vision comes first, the numbers and strategies follow. Even so, this first session has a very concrete goal. By the end of the meeting, we will answer two questions: 1) whether I can help your family and loved one with special needs and 2) whether you want me to. If the answer to both is 'yes,' I will send you off with homework: to collect and bring to me certain documents and records.

How does the input work?

At the beginning of the input stage, you do the work. You provide me with copies of your documents; for example, account statements, income and expense records, wills and trusts (if you have them), insurance coverage and so on. We talk about variables like expected inflation and asset return rates and determine where we are comfortable. We open up questions of future life and situation change. Then, you get to take a break. It is my job to input all the data and assumptions and to create projections for the future of your loved one with special needs. Simply put, I answer these questions for you: When will our child need money? And how much money?

What do you mean by fine tuning?

Once the model is designed, we want to sit down again, look at the input and the results and ask these questions: Do these make sense? Have we included all income sources? Have we included all expenses? Do you really have a surplus or deficit of this size at the end of the year? What about that holiday, new car windshield, little cash gift from great Uncle Bill, tax refund, increase in auto-insurance premiums? Would you feel more comfortable assuming a more conservative rate of return? What if your child with special needs does begin to work in the community? What if he does not stay at home? The important thing here is that you feel comfortable with the input and the output.

What about strategy?

If necessary, I adjust the model after which the fine-tuning stage segues into the strategy session. The strategy session is where we talk about how we are going to have money available for your child when he needs it. We talk about how we are going to protect assets for her benefit in a way that she can still access government programs. We talk about specific insurance and investment products and particular ways of employing those products. We talk about the pro's and con's of different products and approaches. We talk about future flexibility. I consult, you decide. The important thing here is that you understand what you are getting, why and how it works, what it costs and what it delivers.

When do we begin to implement?

When you are satisfied that you thoroughly understand and agree with a strategy and the use of certain products, you apply for those products and begin to implement. It is up to you to follow through with implementation, but it is up to me to make sure that you have all the information to make you comfortable with following through.

So are we done, now?

Actually, no. In fact, we have only just begun. Working with a financial planner is a lot like starting an exercise regime with a personal trainer. The reason it works is not just because the professional trainer sets you up with a solid, tailored program, but because he or she meets you in the gym on a regular basis to check your technique and progress and to assess whether the program needs to be changed. Our success is determined in much the same way, except that some of our follow up coaching takes place over the phone. Even so, we commit to sitting down face to face once or twice a year, or any time life changes dictate. This is my commitment, but it must be yours as well.

9th World Down Syndrome Congress

Exploring the Neurobiological Basis for Cognitive Problems in Down Syndrome. William Mobley, M.D., Ph.D. Stanford University School of Medicine. 9th World Down Syndrome Congress Presentation. Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

Down syndrome (DS) is caused by an extra copy (i.e., trisomy) of chromosome 21. Cognitive problems are experienced by people with DS throughout the lifespan. Children with DS show varying degrees of cognitive slowing. All people over the age of 40 years with DS show the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and many people suffer further cognitive decline (i.e., dementia) in their 60s and beyond. Until very recently, scientists saw the problems posed by an extra copy of an entire chromosome as too complex to analyze. Moreover, it was believed that since DS problems arose during development, little could be done to reverse the damage. Fortunately, recent scientific advances have brought new tools and concepts to the biology of DS. Using modern genetic technologies and the results of the human genome project, it is now possible to define the gene(s) responsible for any atypical feature in people with DS. Moreover, advances in neuroscience have made it feasible to discover these changes, elucidate their mechanism, and develop new pharmacological therapies. The insights developed through this research not only will help children with DS, but also will have a direct impact on new treatments for Alzheimer's disease. One cause of cognitive problems in DS evident from structural and functional studies is that the hippocampus-a brain region whose function is critical for brain regions. Also, we know that basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCNs), which innervate the hippocampus and are critically important for learning and memory, are abnormal in both children and adults. It is therefore believed that BFCN dysfunction and degeneration contribute to developmental and age-related problems in cognition in both Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. But as yet there is no insight into how this is caused or how to ameliorate dysfunction of BFCNs and thereby enhance cognition.

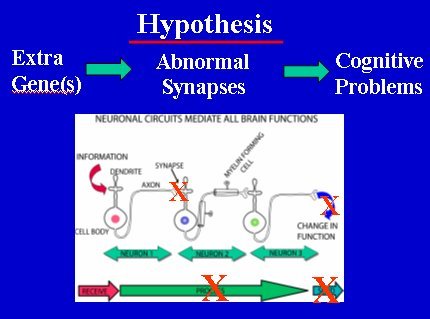

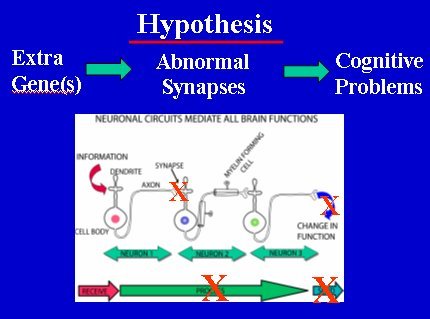

The hypothesis that guides our work is that each cognitive abnormality in DS is due directly or indirectly to increased expression of a specific gene(s) on chromosome 21. By discovering the responsible gene(s) it may be possible to prevent or rescue the defect. Our studies place a particular emphasis on hippocampal circuits that mediate learning and memory. We examine mouse models of DS and define changes that recapitulate those seen in DS. The Ts65Dn mouse model has a third copy of a portion of mouse chromosome 16 which is very similar to human chromosome 21 in that it contains an extra copy of about 140 homologous genes. Importantly, these mice show abnormalities in cognitive tasks mediated by hippocampus, including defects in spatial learning and memory.

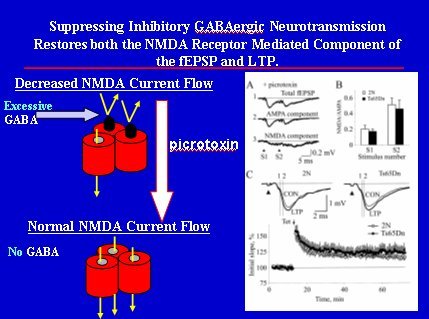

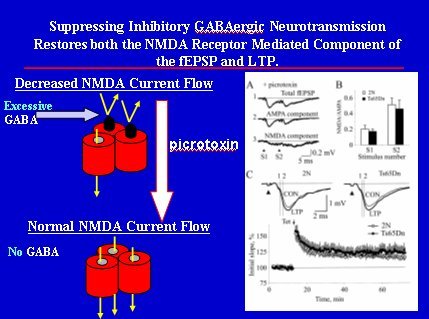

Studies in young mice have shown abnormalities in the structure and function of synapses that closely resemble those in people with DS. Our findings point to an increase in inhibitory neurotransmission that could compromise circuit function and impair learning and memory. We will discuss the findings and indicate how ongoing studies are attempting to understand and overcome the abnormalities detected. BFCNs are responsible for the cholinergic innervation of the hippocampus. Cholinergic innervation of the hippocampus is known to be important for short-term spatial learning and memory. Atrophy and loss of BFCNs are consistent features in people with DS and AD, a change believed to contribute significantly to the resulting cognitive difficulties. The Ts65Dn mouse exhibits the abnormality, showing progressive age-related atrophy and loss of BFCNs within the hippocampus. We have explored the cause for BFCN degeneration, gathering evidence that failed signaling of nerve growth factor (NGF) is important. NGF, which is produced in the hippocampus, is critical for the normal development of BFCNs and for maintenance of their integrity and innervation of the hippocampus. We discovered that in DS mice there is marked disruption of NGF retrograde transport to about 10% of normal levels. To ask whether or not this was significant, we bypassed the defect by administering NGF directly to the cell bodies of BFCNs. This resulted in complete reversal of the atrophy and apparent loss of BFCNs.

|

|

| Slides courtesy of William Mobley, M.D., Ph.D. |

These data strongly supported the view that in the absence of sufficient retrograde transport of NGF within signaling endosomes, BFCNs become shrunken and dysfunctional, but do not die. We found that a region containing about 40 genes was needed for the defect in NGF transport and BFCN degeneration. This region included the gene for amyloid precursor protein (App). To test for what role App might play, Ts65Dn mice were mated with mice heterozygous for deletion of App. The offspring included TsSDn mice with either 3 or 2 copies of APP. The mice with two copies of App showed no defect in BFCN size. Importantly, deleting the third copy of App also markedly increased NGF transport. These data are evidence for an important role for the third copy of App. This suggests the pathogenetic sequence: Increased APP Expression → Decreased NGF Transport → Loss of BFCNs → Abnormal Cognition. Thus, even in the context of a complex genetic lesion, overexpression of but one gene can produce important changes. We are now exploring the mechanism for disruption in NGF transport and are beginning studies to show whether or not reducing APP protein levels can prevent or reverse the deficits in transport and BFCNs.

Exploring the Neurobiological Basis for Cognitive Problems in Down Syndrome. Commentary by Dr. Teresa Cody.

I would like to extend my thanks to Dr. Mobley's Stanford University Down Syndrome Research team. They are moving research into uncharted territory and uncovering positive discoveries for more treatment options. (Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation Suppressed by Increased Inhibition in the Ts65Dn Mouse, a Genetic Model of Down Syndrome. J Neurosci. 2004 Sep 15; 24(37):8153-60)

This is the most exciting time in the history of DS research with the advent of a genetically engineered DS mouse, this means to add or subtract a gene or genes to/from that mouse.

- Produce mice that have DS. That means mice with an extra copy of the smallest chromosome, which exhibit DS phenotypes.

- Produce second and third generation DS mice in where extra segments of the extra chromosome are deleted. Then determine if the absence of that segment reduces or eliminates the DS phenotypes/abnormalities.

With these technical advances, delivering a treatment is possible.

Stanford first looked at the brain region critical for learning and memory. They examined structure, as well as, function. It turns out they go hand in hand.

Two problems emerged. The shape of the end of the nerve is too big and the nerves are not being used. Like muscles, without use, the nerves become weak and do not maintain their proper shape.

This may sound impossible to treat but the scientists figured out why the nerves were not working. The GABA receptor is turned on all the time, shutting down the rest of the nervous system. Stanford is now working on developing a pharmaceutical product that will turn GABA down to the right level. In the meantime, the herb Ginkgo Biloba, which has been used for years to increase memory in the elderly, is a mild GABA antagonist, i.e., turns GABA down. (Bilobalide, a sesquiterpene trilactone from Ginkgo biloba, is an antagonist at recombinant α1β2γ2L GABA(A) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003 Mar 7;464(1):1-8)

The University of Sydney has been studying the GABA receptor in detail and concluded that Ginkgo Biloba is a safe, effective GABA antagonist. (Ginkgolides, diterpene trilactones of Ginkgo biloba, as antagonists at recombinant α1β2γ2L GABA(A) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004 Jun 28; 494(2-3):131-8)

The next step being studied is why is there a lack of maintenance of the nerves? Nerves must be maintained with chemicals called growth factors. These growth factors (little packets of nerve nutrition) are transported down a nerve 'highway' if you will. In the DS mouse model, the scientists discovered the highway was shut down and no growth factors made it to the nerves. This leaves the nerves vulnerable and unable to survive.

The good news is that when the highway was bypassed and growth factors were placed directly on the nerves; the nerves revived as if they had been sleeping, not dead. Stanford used the DS mouse to narrow down the responsible gene(s). The likely candidate is a gene called APP. This acronym may be familiar because it is being studied extensively in Alzheimer's disease.

Treatment options include turning down the expression of APP or increasing availability of growth factors.

Dr. Mobley's presentation truly gives us insight into new avenues of treatment. At one time, Down syndrome was considered too complex to resolve but as with other medical mysteries, it is being unraveled by modern day science.

Dr. Teresa Cody, University of Texas Dental Branch 1992; Bachelors Degree in Biology from the University of Texas in Austin, 1988. Dr. Cody has a private practice in the Houston area that specializes in children with disabilities. She served on the Down Syndrome Research board 2004-5, spearheading the Adopt a Mouse fundraiser and is an advisor to the Down Syndrome Association of Houston. See: http://www.changingmindsfoundation.com.

Down Syndrome Articles

The Five Goodbyes. Mothering My Child with Down Syndrome. Copyright © 2003 by Pat Ferguson Hanson. ISBN: 1-4134-3209-3. Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris Corporation.

Prologue. Molly, p. 21-22.

I still cry. Will I ever stop? It's still so sad. Will I ever get used to this? Will it ever feel okay? Will it ever be settled?

She's still my baby, my only birth child. And she doesn't live with us anymore. And she's only five.

Who will teach her to read? To ride a bike? To swim? To worship? Does she know we still love her? Does she know our pain? Does she understand why she can't live at home?

Hell, how could she? She's only five and she's developmentally disabled and she doesn't speak all that well. So we don't talk to her as much as we do our other children, whom we tell almost everything.

It's impossible to know what she understands because we don't exactly have conversations. It's more like words. Saturday she said, "house," repeatedly. She meant our house but we had to say, "no," repeatedly, because we were only taking her out to dinner this time. It's all I could manage. I was still recovering from the last overnight Molly spent with us, when I found her excrement from one end of the couch to the other. Maybe she understands more than we give her credit for. She cried when we took her back after that overnight and she clung to me. Jim says she adjusts to where she's going because she knows she has no choice. There is a quiet sense of resignation I see move across her face when she passes over the threshold of the Foster Mother's home. She knows she has no choice; like a prisoner, she adjusts.

Daily we ask ourselves if we have a choice or if there is a better one out there and if we'll have the option or courage to exercise that choice or if we'll just keep wondering and, like Molly, with quiet resignation, say our goodbyes to her weekly at the Foster Mother's house and return home without her.

7/15/96

Published in "River Images" (the literary magazine of the St. Croix Center for the Arts, Taylors Falls, MN), Winter, 1996-97; and accepted for publication by "Room of One's Own," a literary magazine in Vancouver, BC, Canada, July, 1998.

Molly's First Day of Kindergarten, p. 250-252

My youngest child is now in grade school. Today Molly started kindergarten. It is not her home school. In fact, she no longer lives at home. Molly is in foster care in Cottage Grove, Minnesota, about an half-hour from our home in Stillwater, Minnesota. Ironically, we bought this home in large part because we expected our three girls to all attend the same grade school, Lily Lake, our school district's cluster site for the Mildly and Moderately Mentally Impaired. Ah, "the best laid plans of mice and men ..."

Once again, I felt torn by the competing needs of my different children. I needed to be in Stillwater to get my two older children to school. This was Maya's first day in first grade; Tina started third grade.

How I wanted to be in two places at one time, so I could see Molly off to her first day of kindergarten. Instead, we had to settle for my picking her up at school and taking her to lunch afterwards at her favorite restaurant, McDonald's.

I couldn't wait until lunch, however. I went right over to Molly's school after getting Tina and Maya settled in their school, stopping only at Target to try to buy Molly's favorite book, "Brown Bear, Brown Bear," which, miraculously, she read to me two weeks ago. I had very real fears that she would never read, given the fact that her hyperactivity had always made it impossible for her to sit still long enough for me to even read to her. She may have just memorized this book from all the times I'd tried reading it to her. Still, she turned the pages, one by one, and read the book to me, cover to cover. I cried. I still can't believe it. Perhaps the drug, Ritalin, we're trying again, is helping her to focus.

I stopped in the school office to ask how to find the special ed. teacher/office and Molly's room. The secretary said she was expecting me to pick up Molly for lunch, but happily showed me where I needed to go, adding, "What a cutey Molly is."

She did look darling today, in the new pink and white shorts outfit I gave her over the weekend. Her hair was done just so, with barrettes and every kind of adornment in it. She had her glasses on and was sitting perfectly, just like all the other children, eating her snack of cookie and milk when I came in. She was very excited to see me and share her first day of school She deposited her trash where asked and cleaned up after herself very well.

Next on the agenda was story time. Lo and behold, the story was "Brown Bear, Brown Bear!" I could not believe our good fortune. When the teacher asked, "Who can read?," I helped Molly raise her hand. We all read the book together. Not everyone understood Molly's enunciation or why she was sometimes a beat behind the others in getting the words out, but I couldn't have been prouder of her.

Then the principal came for a visit. I told Molly his name and she kept calling it out and saying, "Hi!," which to her and me seemed like a friendly enough thing to do. Again, not everyone understood her enunciation or her need to engage in perseverative speech. (The doctor said the Ritalin won't help with this.) Molly was encouraged to "Listen."

Still she said "Bye!" to the principal several times as he left the room. We were happy to hear him return the "Bye!"

I was also happy she was no longer running out of classrooms and down the hall or breaking the glasses of the child next to her, both of which she had done in pre-school along with biting, kicking, scratching and hitting. I knew I was seeing real progress. But then Molly was in a classroom full of people who didn't have all that history with her, which isn't all bad.

Finally, it was time to "Draw a picture of yourself and put your name on it." My heart stopped. I knew the drill. After all I had watched Maya do this just a year ago. She and I were both happy to have that picture and signature on the wall with all her classmates' for as long as her teacher cared to display it, which might have been all year.

I knew Molly was still at the circles and lines stage in terms of drawing and printing. I couldn't help myself. I had to help her, not because she or I wouldn't think her art and writing good enough, but because I was worried about how the other children might respond to it and how long it might be up. I helped her draw yellow hair on her circle and put blue dots where the eyes should be. We added a nose and ears, and dressed our stick figure in pink shorts and a shirt. We formed the letters M-O-L-L-Y as she called them out and finished with a flourish, saying "Molly!," as we have for months now. It was good enough and we had a good time doing it.

Still, it had been hard to listen to the instructions at the outset of the assignment. "Don't pick up your crayons yet." She couldn't wait. Like her artist Father, she loves to draw. Again, I was just thrilled she was sitting where she was supposed to and wanted to do this project. Knowing how difficult, if not impossible, it is for her to sit still, even on Ritalin, I probably would have let her get started. Are the class expectations too high for Molly or are mine not high enough?

The staff said they had no idea how she could talk until I showed up, when she couldn't stop talking. I won't pretend it's easy for me to listen to her perseverative speech. I seem to get it the most. Perhaps because I'm the one who always responded to her whenever she tried to speak and strained, as Mothers do, to make out every word she said, long before others could find it intelligible.

Staff also said Molly cried when they took her glasses out of her backpack and put them on her. They understood our need to "pick our battles" with her. She's supposed to wear glasses all the time; we've settled for her wearing them in the classroom.

When checking her backpack, staff had also noticed "Pull-ups" and wipes. I had her diaper bag in the car for our lunch trip, something we'd all hoped we'd be able to live without by now. But there is progress on this front, too. When taken to the bathroom by staff, Molly had "performed" today. Thank God for small favors. I decided to leave the class and return for Molly at lunch, as originally planned. I knew I needed to rest up for what that occasion would demand of me, and also that Molly might pay more attention to her lessons if I wasn't present. Besides, nobody else's Mother was there. And, as much as I know Molly will never be just like everybody else in her class, I wanted as much as possible for her to fit in this, her first day of kindergarten.

Web Wanderings

Father's Journal

Dual Diagnosis

It is bedtime and a father in a poor Mexican border town cannot bless his son with the sign of the Cross. His baby born ten years ago with Hirschsprung, just like you, sent home from the hospital to die with a distended belly, throwing up green bile, just like you.

|

|

New Recommendations for Down Syndrome Call for Screening of All Pregnant Women. ACOG News Release. January 2, 2007. URL: http://www.acog.org/from_home/publications/press_releases/nr01- 02-07-1.cfm

Washington, DC — All pregnant women, regardless of their age, should be offered screening for Down syndrome, according to a new Practice Bulletin issued today by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Previously, women were automatically offered genetic counseling and diagnostic testing for Down syndrome by amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS) if they were 35 years and older.

[...] Practice Bulletin #77, "Screening for Fetal Chromosomal Abnormalities," is published in the January 2007 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.