Looking up at Down syndrome, p. 1-16

Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan

Director, the Hadassah-WIZO-Canada Research Institute, Jerusalem

Tel Aviv, Israel, 61350

972-3-562-8540

Fax: 972-3-562-8538

|

Reuven Feuerstein Looking up at Down syndrome, p. 1-16 Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan Director, the Hadassah-WIZO-Canada Research Institute, Jerusalem |

Reproduced with the permission of Freund Publishing House Ltd.

P.O. Box 35010 Tel Aviv, Israel, 61350 972-3-562-8540 Fax: 972-3-562-8538 |

I was asked to talk on "The human potential of persons with Down Syndrome: a future-oriented perspective." Since this invitation, I became the grandfather of Elhanan Perez, a child with Down Syndrome so that now I am not speaking to you purely as an objective, scientifically oriented behavioral scientist, but also as the grandfather of a child with Down Syndrome. In this respect, I would like to make some personal remarks.

In the past, when talking to parents whose child was born with Down Syndrome, I would try to encourage them, counsel them, and bring in a note of optimism and a sense of their own power to master in the very difficult situation in which they found themselves with the birth of this child. I would ask myself sometimes to what extent could I find this strength if I were one of these parents. From the tone of the parents whom I was counseling, in many cases, I could feel their question: Would you be the same if you were in this, situation? Would you be as optimistic as you are trying to make us feel?

At two o'clock in the morning, when my son called to tell us of the birth and then slowly added that the doctor suspected that the child had Down Syndrome, I felt what probably everybody feels. Then I saw the child in his mother's arms. Such a beautiful child. I was immediately able to see the new hope which we had lying in our hands in contributing much more meaningfully than usual in the making of a human being. Then too I felt forces mobilizing in me. My adherence to a very optimistic view of human modifiability has enabled me to overcome many of the difficulties inherent in the situation. I feel that I am better equipped than the usual parent to cope with this condition. I do not perceive myself as being totally incapacitated in handling and improving the situation. This has given us a very different outlook in confronting what has happened.

I understand very well the reactions of parents who, learning about the birth of a child with Down Syndrome, run to the encyclopedia to clarify what it is that has happened to them. What do they learn from the Encyclopedia Britannica (1972 edition)? That their child with Down Syndrome is categorized under the concept of "monster." Parents who learn that their child is a monster may have very little effect or power to mobilize in order to change their child's condition. The truth is that they go into a state of depression. Their capacity to bond with their child, to engage in warm interactions, is meaningfully diminished. At the protest of irate parents, the category was changed in the 1973 Encyclopedia. The Down Syndrome child is now classified under the title of "malformation, biological." Nothing has really been changed; yet, the fact that the child is no longer labeled as a monster will offer parents a much better entry into their relationship with their child than was previously possible. Such parents' general view that their child is mentally retarded does not permit them to become active in their transactions with the child and reduces their attempts to modify the child's role, quality of life, level of functioning, and his cognitive structure. The fact is that until now Down Syndrome has been equated with mental retardation. Even very progressive and important scientists have, as late as 1979, labeled the Down Syndrome child as mentally retarded.

Some children with Down Syndrome learn to speak a little and to master simple chores. In most cases, however, they cannot learn to speak or can utter just a few hoarse sounds and they seldom learn more than elementary self-care (sic). From time to time there are reports of remarkable achievements in raising IQ scores of subnormal children. Headlines in newspapers and articles in magazines raise the hopes of countless parents who have retarded children. This publicity is unfortunately misleading, because the overall evidence we have today is not encouraging. It gives little promise of dramatic improvement in the mentally subnormal, although this does not mean that the retarded or defective child cannot be helped (p. 370, Hilgard, Atkinson, Atkinson, Introduction to Psychology, Seventh Edition).

In light of such statements from eminent psychologists, parents do not perceive themselves as able to do anything. Basically parents and educators are told there is nothing they can do but make the child's life more comfortable, to offer him/her love. They feel they must accept the child as he/she is or totally reject him/her. Many parents do indeed reject or not accept their child at first. They relate to this child very differently than they would to a normal child, using a passive acceptant approach. You will hear again and again from the parents of Down Syndrome children: "The child must be accepted as he is. Do not attempt to change him. Try to modify the environment so that it will fit the child's fixed and immutable capacity. The child has the right to a quality of life which can be given to him by the type of requirements the world has for him; these must take into consideration his unchangeable condition. This quality of life is due to the child and does not depend on a child's activity or understanding.

That love is not enough is more than obvious, because this kind of passive acceptance will lead to a very restrictive type of life for the child who will be offered affection, even emotional closeness, but not the type of development to which he/she has the right. Thus approach, which is encouraged by the kind of psychology and educational systems quoted above, perceives the human being as fixed, immutable and unchangeable. It is a totally inappropriate way of dealing with a Down Syndrome child. As a French journalist summarized, "Les chromosomes n'ont pas le dernier mot." (For Feuerstein the chromosomes do not have the last word.) Of course, they do determine the nature of the individual's level of functioning and the investment needed for learning. Does it mean that the limitations imposed by the chromosomes are totally unacceptable? No. When we discuss the role of the chromosomes and the role of the individual's neurophysiological conditions, we try to isolate the various factors. Is it the chromosomes which determine the child's present condition or does this condition actually reflect our social way of perceiving this child? Do only the chromosomes determine the level of functioning, or does the passive acceptant handling affect the child's functioning?

The theory we would like to present here Is the theory of Structural Cognitive Modifiability which describes the plasticity, flexibility and the modifiability of the human being as a uniquely human characteristic. It is this plasticity which enhances the human being with a propensity to overcome endogenous and exogenous determinants and enables him/her to become modified in behavior and functions. By the concept of "structural modifiability" we describe changes in internal mental, emotional and motivational processes which permit an individual, once modified, to continue to grow and develop. We view the human being as an open system which can be affected by processes of intervention, with the stimuli impinging on him leading to greater modifiability in the direction of ever-broadening cognitive processes.

Conventional approaches with their view of the immodifiability of human intelligence usually consider these processes accessible only to those individuals who are considered disadvantaged by their environments, cultural differences or inadequate cognitive development. However, those whose low functioning is determined by endogenous factors such as chromosomal aberrations, metabolic errors and organic conditions are considered as inaccessible to intervention which would make them able to change their cognitive processes in a structural way. As a result of this approach, education of the endogenously affected individual, of which the Down Syndrome child represents a meaningful paradigm, is limited almost volitionally to very menial, low goals of survival skills, social interaction and affection, and is totally devoid of adaptational meaning and occupational, civil and social acceptability.

The capacity to perceive adequately, to produce relationships among the perceived events, to create new information by extrapolation and logical thinking, to anticipate, and to represent to oneself the unperceived reality all these functions represent are all important conditions of our adaptation to life. In order to adapt to the ever-changing complexity of our world, we must be able to change ourselves, our information, our views, our strategies, and our ways when responding wherever they are no longer adequate. It is by changing ourselves and our behavior that we adapt to life. From this point of view, to limit the Down Syndrome child's type of education to some social intelligence, to teach him only how to handle himself, how to become more familiar with certain restricted areas of interaction is just not enough. We must consider the Down Syndrome child as having the possibility, and certainly the right, to become able to adapt to changes in situations both outside of himself and inside of himself via cognitive development.

This type of education has been denied to the Down Syndrome child for many years to the point that very few have been given the opportunity to learn, to actively communicate in a way which enables them to be part of the total interaction. They were not given the opportunity to read, to understand, in a way that would permit them to gather new information beyond that which was immediately experienced. They were not given the opportunity to learn to think in a direct, efficient way. Nobody believed that these individuals could go from their manifest levels of functioning to generate new information.

Our basic belief is that much of what we observe in these children is directly linked to the stereotyped views we have of the individual, as has been described in "The Introduction to Psychology." We have attempted to do very little with the Down Syndrome child, in many cases we have been discouraged, "Don't do it to him." I can tell you the story of a professor of psychology who brought me a 20-year old Down Syndrome youngster for examination. Before I started the dynamic assessment, the professor came in to ask me a favor. "Please, Reuven, don't teach him things he doesn't know." This young man had never been taught what is right, what is left, what is horizontal, what is vertical. In 15 minutes, he was confronted with trying to understand that the right hand of a person across and facing him was the opposite of his own right hand. Suddenly and excitedly, he was telling us how many times he had suffered from the fact that he had been unable to tell a person opposite to him in what direction to go. He had always been forced to point the way rather than being able to use words to describe direction. will never forget the excitement of this very pathetic young man.

In order to make an individual accessible to change, there are some basic and common sense rules to follow. For example, don't place the child in an environment where the same program will be repeated with the same teacher over and over again. He/she may be passive because the environment is too familiar. He may eventually become competent in the nonpromoting environment, but it is a very poor type of competence. We must shape environments so that they create a need and offer possibilities to the individual to become engaged in a process of change.

There are a number of applied systems derived from the theory of Structural Cognitive Modifiability which are useful with a variety of populations. These include the culturally different, the culturally deprived, individuals who are socially disadvantaged for various reasons, persons who have internal barriers to the learning process (such as the child with Down Syndrome) because of deficiencies in organic conditions. But, a human being as a modifiable entity, as a changing entity, strongly depends on the nature of the interactions which human beings have with their fellow men. From this point of view, irrespective of being gifted or just average, if one has not had the opportunities of interacting with intentioned adults as mediators, one's cognitive functioning is not developed to its fullest capacity. The child with Down Syndrome requires more mediation than the regular child, but the mediation, although greater in intensity and frequency, is not different from what we all need in order to develop ourselves as modifiable, flexible human beings, capable of adapting to life conditions. The "mediated learning experiences "of the Down Syndrome child may differ quantitatively, but are basically the same as those needed by all other human beings.

The concept of Mediated Learning Experience is an attempt to answer a specific question: What is it that makes human beings as modifiable as we postulate? What is it that makes an individual capable of changing not only in response to external needs, but also in response to internal needs? What is it that has made the human being evolve as the changing entity we know him/her to be? In addition, of course, to some physiological characteristics in the human constitution, we consider that the major determinant of this modifiability is the type of interaction which the human being has with his/her environment, an interaction which no other living existence has. It is superfluous to say that this mode of interaction is possible only when the neurophysiologial and constitutional basis is present which enables the socioeducatonal interaction to take place. However, it is this special interaction which is responsible for most of human modifiability.

The most pervasive and most generalized type of interaction humans have with their environment, also common to the animal realm, is through direct exposure to stimuli. Both the stimulus and the response modify an individual. The stimuli with which an individual is confronted at a given point in life for the first time remain very different than when they are experienced again the second and third time. As a person, therefore, one reflects changes in functioning. Seeing and feeling change one's response, one's interaction with the situation. For instance, a child may pick up a piece of chalk, put it into his mouth and try to chew it. Very soon he throws it away. The next time he encounters the chalk he may try to write with it instead of chewing it. He will not repeat what "he has done; he has learned. He has become modified from this type of exposure.

There can be various levels of changes produced in us in relation to a particular, isolated stimulus. For example, we are all familiar with the child approaching a hands-on museum exhibit. He may turn the glass bowl and incline the glass downwards, but from this experience, he will rarely, if ever, learn what is really happening. He may learn that if the glass is declined, water will run out in the direction he wants, but he will not have learned that the water level in the glass will always be parallel to the gravitational line. We do not discover gravity through direct exposure to stimuli and our pouring an object from our hands and throwing it way. It took quite a lot of time until Newton conceptualized gravity. The kinds of changes that occur in us as a result of direct exposure to stimuli are not enough to explain the incredible changes which occur in our minds following our experiences with stimuli. We must seek another explanation for what happens to us.

The second modality of interacting with stimuli is the mediated learning experience which can be expressed in the following equation:

|

| Figure 1 |

in which S Is the stimulus, H is the human mediator, 0 is the organism, and R is the response. As you can see, there is an H, a human being who interposes himself between the stimulus and the organism, and between the organism and the response. The mediator changes the stimulus so that it becomes salient to the child. The mediator has an intention, wanting the child to perceive the stimulus. In order to make the stimulus obvious, he/she exaggerates and amplifies movements so that the child will focus on the stimulus and eventually learn. The mediator creates an organization. The mediator creates relationships: something falls down and he/she picks it up again; it falls down again and is picked up again. Eventually there is an evolvement of a relationship and a generalized rule formed between the object, its falling down, and its being picked up.

If you look at the figure above, you see lines going through the H. Those represent the stimuli which are modified and changed by the mediator. The stimuli are different; they are amplified, organized in time and space and can be distinguished from non-mediated stimuli. The mediator not only produces in the mediated information about this particular stimulus, relating to this specific event, but also produces a propensity and facility to learn, a way to observe. The mediator imposes temporal and spatial organization: "Here, not there"; "Then, not now". The mediator creates in the individual the dynamics of processes of change. By comparing what he/she was and did yesterday with what he/she is and does today, the individual will be able to discover for him/herself the world of tomorrow, being able to anticipate and represent beyond the immediate visual field. The mediator creates the future dimensions which become as vivid as the present; the future becomes perceptible and anticipated. By this, we have forged the way for using whatever is learned for meaningfully modification.

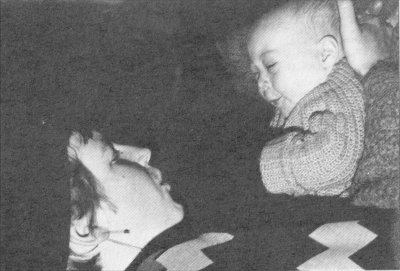

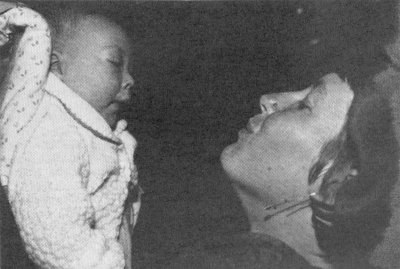

In the pictures, one sees how the child's perception is affected by making him focus on the mediator's facial expression. This has been done through hundreds of repetitions with the intent of the mediator to make the child imitate some of the mediator's behaviors. There is a constructive nature to the mediation; it is not merely that the child sees or does not see. The child sees the exaggerated lip movements, but does not just do what he/she sees. He/she makes all kinds of faces, constructing the movement rather than just imitating it. The protruding mouth of the child is associated with the sounds "boo," and "baa." You see the enormous effort the child makes in order to imitate the mediator's behavior. This can be compared with other facial movements which the child is able to learn to imitate at an early stage (for instance, the child's capacity to imitate the protruding tongue). The important part of this phenomenon is that what previously took 200 repetitions by the mediator to elicit can now be achieved by only two or three repetitions. Not only with this particular type of behavior, but many other types of behavior as well. We refer to this as "mediated imitation". Mediated imitation is a way of learning. The child was taught how to observe, how to focus, how to imitate, how to construct various types of behavior. By this, in a relatively short period, the child has been made a good learner, an imitative learner of types of behaviors which are dependent on the nature of the movement of lips and so on. From this point of view, the mediated learning experience has a number of parameters which tend to create within an individual the flexibility we consider as typical of all human organisms, including the child with Down Syndrome.

The first of these parameters are intentionality and reciprocity. The mediated learning experience is always accompanied by an intention on the part of the mediator to get the message through to the child. In the case of a child who responds slowly or seems not to reciprocate at all, intentionality mush lead to an unyielding, yet careful and consistent plan of action. Thus, if the adult's intention is that the child learn to know a certain object, its name, its features and its functions, he/she will not be satisfied by merely placing an object in front of the child, but will see to it that the child will see it, focus on it, and follow it. The mediator will even bring the object close to the child. If the child is hypotonic, the mediator will place the object so that the child can indeed see it, and/or bring the child's hand to it to touch it. The mediator will repeat or change the action, the word or the activity many times until a response is elicited from the child.

Another primary parameter of mediated learning experience is the transcendence of the interaction beyond its immediate goal. While focusing on a specific topic or basing the interaction on some common activity, the mediator will create a broader frame of reference and relate the here and now to more general concepts and dimensions of human experience. Thus, for example, in feeding the child at a given place and time and in a particular way, the mother does not respond only to the immediate need to satisfy the child's hunger, but also mediates the meaning of space and time, and the significance of her relationship with the child, thus also enlarging his/her system of needs.

Mediated learning experiences are viewed as an effective way of orienting parents to the rationale and meaning of what must be done to make their child a better learner. This does not mean that parents are told what they must or must not do. Parents must do what comes naturally, but mediated learning experience helps them to become better at this. One of the great difficulties in parent training programs is that parents are presented with a great number of restrictions. In their natural interactions with their child, parents do what they can do and do not do what they cannot do.

I want to mediate for my child. How can this be materialized? (There are a great number of people, including Yael Mintzker and Elizabeth Zausmer who have been using mediated learning experiences in the field of assessment, motor development and cognitive development). Let us say that I want the child to see how my mouth moves, what do I do? I do three important things: I transform the stimulus; I modify the child; and I change myself into a mediator. I change the stimulus and make the child perceive it by exaggerating and amplifying it. I increase the vigilance and alertness of the child to cultivate more awareness. I modify myself by acting very differently when I want to mediate and make the child experience the object experience. I modulate my voice; I raise its intensity. I change my stance. But most of all, I make the child see. (Sometimes I even wake the child in order to notice something I think is that important.) As a mediator, I impose myself upon the child. Throughout life, and not just in early childhood, I impose my focusing. I also impose many things he/she does not yet have. He/she does not know how to respond so I mediate to make the response available. My intention to make the child accessible to a particular stimulus will result in changing all three partners in the interaction: the stimulus, which will be repeated as much as necessary to make it penetrate; the child, who will be made more alert; and myself, the mediator. I will change myself very meaningfully by virtue of my Intention to turn this child into a better learner.

Because of internal barriers, the particular type of condition, the lack of alertness and slowness, the Down Syndrome child does not just need exposure to stimuli. The child cannot be placed in front of many stimuli with the hope that they will be perceived and somehow penetrate his/her system. It won't happen. The stimuli must be mediated. This concept is not limited to a child with Down Syndrome. There are highly gifted children who have not received mediated learning experiences because they lack the patience to attend to the mediator. They run directly to the stimulus. They grasp it by themselves. They know it by themselves; they do not feel they need mediation to make them attend. What happens to this gifted child? He/she is often a gifted underachiever. The gifted child does not receive mediation because of rapid reactions and impatience for slowing down in the anticipation of a mediator. The Down Syndrome child may not receive mediation that is proffered because of slowness. There is need for fifty times the mediational intervention given to the gifted child. On the other hand, if mediated to twice, the gifted child would probably not attend. With the lack of appropriate mediation which is adapted to the particular needs of the individual, both the gifted and the Down Syndrome child may end up as underachievers.

What we attempt to convey to you stems from our own positive experiences, with a great variety of children, particularly with the child with Down Syndrome: they can be brought up to levels of functioning which are much beyond what is believed to be their limits. We must offer these children the optimal conditions for change. They may need a high level of intensity and a high level of frequency. We must be creative in order to make the child attend to the stimulus, to make him attend to the relationship, to learn new ideas. Children with Down Syndrome require much more than is usual for other children; but this does not mean they are not receptive. They must be made receptive and aware by making them go beyond their barriers.

Mediated learning experiences need not be limited to a particular event in interacting with the child. For example, as mentioned above, in interacting with the child who is eating, one must make sure this act will not remain limited to filling the need for survival. When feeding the child, certain rhythms, certain changes in motor behaviors can be produced that will affect his cognitive structure. The same is true for other types of interactions. From this point of view, a mediated learning experience goes beyond the immediate need of the event that has elicited the interaction.

An essential attribute of mediated learning experience is the mediation of meaning. I want this child to be modified; I want him/her to learn something. I want the child to perceive the type of relationship between a stimulus and a response. I would like to imbue what happens today with a particular meaning so that the child will be able to see the transformation of relationships between this particular day and the particular set of events that are happening. I would attach to each of the days a special meaning of the events which the child has experienced. I would thus convey a true meaning of the importance, desirability, and justifiability of making each day meaningful. I am making the child vibrant to what I want him/her to experience. I convey exuberance when I want the child to be excited about something. It is this particular quality of meaning that I convey to the child that will make much of the learning important to him/her.

I trust this brief description of the role of the mediator in mediated learning experience interactions has conveyed a sense of what we would wish parents to provide for their children.

I would like to conclude my remarks with three important guidelines which I would hope would be underwritten by this International Congress. In order to modify the child with Down Syndrome and in order to offer parents a different attitude as to the possibility of achieving changes, we must first do away with the notion that the child with Down Syndrome is ipso facto a retarded person. Today, unhappily, Down Syndrome is universally equated with mental retardation. This creates a whole set of mental attitudes that taints the relationship we establish which gives a special orientation to the way we perceive this child vis a vis his limits and the goals for his social, occupational, and vocational development. Let us not forget that even today people with Down Syndrome do not have real, lucrative, meaningful employment. Without such goals, we do not prepare our child to become a productive employable individual. We do not set autonomous, independent types of activities in front of children with Down Syndrome. We do not envisage that they will ever be able to establish themselves as members of their own nuclear families, whether or not they will have children. Why do we deny the child with Down Syndrome the goal of living and gaining support from the society of his family to live an independent life? The fact remains that we deny children with Down Syndrome the types of goals which should be available to him no less than to other individuals who are low functioning.

Let us face it. When people say Down Syndrome, they mean mental retardation. Let us work to fully divorce these two terms. I will accept the concept of retarded performers. An individual can be a retarded performer without being retarded. So, let us declare that the concept of mental retardation ascribed to Down Syndrome is not more attributable to that condition than to any other type of individual. There are more retarded people among non-Down Syndrome populations than there are among the Down Syndrome. There must be a call on the part of the Convention to bring the proper relationship between Down Syndrome and mental retardation to the attention of a much larger audience. We must continue in our efforts to do away with the notion that a Down Syndrome child must be mentally retarded.

As a second suggestion, we must help shape reality. We know that the common denominator in all children with Down Syndrome is that they are developmentally delayed. In order to ensure that an individual with Down Syndrome has a chance to become integrated among normal peers, let us delay entry into school by two or three years. Let us synchronize mental development with chronological age. Let us have the right to declare that our child with Down Syndrome, at the age of six, is only four; at the age of four, only three. We may even defend the right to register the child's birthdate as younger by a year, or two, or three, and thus escape all the difficulty we have today of keeping the child in kindergarten for another two years in order to make him grow, come up to, and even surpass other children. Parents should have the right to declare that they want their child to go to school, to make him able to withstand an earlier child environment and be capable of growing up together with younger peers. This would provide a meaningful resolution of problems we now face when we attempt to place children with Down Syndrome in early childhood environments. Our child of six will be with normal four-year-olds and will learn to imitate and learn from these peers. We must begin with a child whose capacity to imitate has been mediated and by virtue of this, will be able to benefit from exposure to regular normal younger children. He/she can learn from them and consolidate whatever learned in a way that will permit participation as a full member of their society.

Our third suggestion calls for legislation on the right to offer the child with Down Syndrome modifying environments so the individual can adapt himself in vocational, occupational types of activities that are usually not available to him. The modifying environment should be anchored in legal approaches, based on understanding, based on belief systems, and based on research as to the true capacities of the child with Down Syndrome.

Our long-term experience, based on an active modificational approach, has provided us with results that fully support our optimistic view as to the effects of mediated learning experience and an intervention oriented towards rendering the individual capable of being modified and of modifying others through his/her interaction with an enriching life experience. Plastic surgery, to be described later by our colleagues, Prof. Menachem Wexler, Ms. Yael Mintzker, Prof. Yacov Rand, Prof. Ronald Strauss and others, has reflected the active modificational approach inasmuch as the parents who decided on this step decided, "We don't accept you as you are. We want your appearance to be changed. We want your speech to be more intelligible. We want you to be accepted more easily into society." Indeed, the knowledge that this child's appearance and speech could be meaningfully corrected has encouraged parents to work with their children and set much higher goals. The fact that a child with Down Syndrome is not automatically considered to be mentally retarded, but someone who can also become involved in higher mental processes as previously described has affected dramatically parent - child interaction and encouraged conditions of richer interaction than before.

Our newest project consisting of training young adults with Down Syndrome to become caregivers for the elderly and handicapped, as will be described by our colleagues, Prof. Harvey Narrol and Debbie Zweibach, has proven to be highly successful and given parents a very different outlook on their child with Down Syndrome than previously held. "Indeed, our child will not be a burden, but will extend a hand to another hand, both of whom need, and both of whom will give and receive help."