Mark your calendars for the National Down Syndrome Society 2003 National Conference in St. Louis on July 11-13 at the Adam's Mark Hotel in downtown St. Louis. The Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis is offering a subsidy to members in good standing for the Teen & Adult Conference. To attend the conference Teens/Adults must be 13 or older and will be required to pay $25 of the registration fee, the DSAGSL will pay the remaining $100. Call the DSAGSL office at (314) 961-2504 to apply and for registration information. NDSS is offering a $100 one-day registration rate. You'll be able to hear experts from around the county - and the world - share their expertise!

1993 Men's Doubles French Open tennis champions Luke and Murphy Jensen are coming to the Metro St. Louis area and joining forces with local tennis professional Vince Schmidt to form the Jensen-Schmidt Tennis Academy for Down Syndrome. The camp is scheduled for August 5, 6 and 7, 2003, 9:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. at the Dwight Davis Tennis Center in Forest Park-St. Louis, MO. The cost of the Academy is $75.00 for all three days and each child and a chaperone will be invited to a free St. Louis ACES professional tennis match. For further information see enclosed brochure or call (314) 606-3639.

We are very proud to publish the following article and photographs sent by the Kane family:

Winning gold medals in Special Olympics is a lot of fun. Joe Kane is twelve years old, has Down syndrome, and loves to swim. Joe won 2 gold medals in swimming at the Special Olympics on March 30 at SIUE. He won in the 50-yd. freestyle and 100-yd. freestyle. Joe has loved the water since he was a baby. Sometimes at the pool when he was a toddler he would just jump right in the pool-when he couldn't swim! This alarmed his mother, but she thought we should capitalize on this love of the water. So she enrolled him in swimming lessons.

|

|

|

| 3/30/2003: Joe Kane at SIUE with 2 Gold Medals. |

When he was about 7 he started on the swim team at Summer's Port in Godfrey with his sister. He has really enjoyed being with the other kids. Everyone cheers for him at meets. He never had a first place until Special Olympics. This winter he also swam the winter swim for the YWCA Tidalwaves. The coach, Nancy Miller, really encouraged him to try the 100 or 4 laps as he calls it. He persevered and was successful. He even swam on a relay team at districts and did very good for the team.

|

| Joe Kane at ISU State Special Olympics: Gold Medal and Fourth Place Ribbon. |

|

Joe got to go to state in Special Olympics at Bloomington-Normal on the ISU campus. He was very excited ad told everyone about it. Joe won a gold medal in the 50-yd. freestyle on Friday June 13 and a fourth place ribbon in the 100-yd. freestyle on Saturday June 14. He was very happy! He keeps talking about the World Games-you have to have a goal! It is so good to see his hard work payoff. Everyone likes to win and have fun. Special Olympics gives Joe a great opportunity for both.

Down Syndrome Articles

Pujols has heart as big as his stats. May 6, 2003. Reprinted by permission of the Evansville Courier & Press, granted by Vince Vawter, E-mail: VawterV@courierpress.com.

ST. LOUIS - Albert Pujols is more than a good ballplayer. He's also a good guy.

No, he's a great guy, Kathleen Mertz and Ethan Schroeder would tell you. The two St. Louis youngsters and their families will be enjoying free vacations to Florida this summer, thanks to the Cardinals slugger's generosity.

The four-day stay in Orlando, which includes visits to Busch Gardens and Sea World, was among the prizes put up for bid last week at a fund-raiser sponsored by the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis.

Pujols, an honorary co-chairman of the event, made the high bid of $3,000 and gave the trip to Kathleen as a birthday present when he found out she was turning 11 the next day. Then he purchased another Florida vacation for the same price and gave it to 11-year-old Ethan, the only other child in attendance, so he wouldn't feel left out.

Kathleen and Ethan have Down Syndrome. So does Isabella Pujols, Albert and Deidre Pujols' three-year daughter.

Pujols said the gifts probably meant as much to him and his wife as they did to the recipients and their families.

"I wanted to cry right there; I was so full of joy and happiness," Pujols recalled. "These kids are so special. I just try to make them smile, make them happy."

The look on their faces told him he succeeded.

"When I told Kathleen, 'Happy birthday; you're going to Florida,' she was so thrilled," he said. "She hugged me and said, 'Albert, you are my favorite player!' "He said both youngsters asked him if he could go on the trip with them. "I told them, 'Maybe - but we'll have to wait until after the World Series.'"

Donna Sarro, executive director of the local Down Syndrome Association, said the 1,400-member organization gets a lot of help from the community's professional athletes, including several St. Louis Rams and Blues players. Rams guard Andy McCollum was the other co-chairman of last week's event "and helped drive the bids up," she said. But probably no athlete does more than Pujols, who is in his third season with the Cardinals.

"Albert's wonderful," Sarro said. "Whenever you get him talking about the kids, he just lights up. Any time we need for something, we can call on him. Diedre, too. They're both very generous of their time."

Last week's golf outing, dinner and auction raised about $20,000, Sarro said, which will be used to help some 1,000 families in the greater St. Louis area.

Pujols will assist with another fund-raiser when he serves as chairman of the association's annual Buddy Walk in September. This event is held in and around Busch Stadium before a Cardinals home game to promote Down Syndrome awareness. Some 2,000 people - including Pujols - participated in last year's walk and raised $18,000 in pledges.

Another generous Cardinal is reliever Steve Kline. He invites 25 Down Syndrome kids to a ballgame a couple of times a year.

"He pays for their tickets, talks to them before the game and sits with them in the dugout to watch batting practice," Sarro said. "He signs autographs, takes pictures and makes sure every one of them gets a baseball.

"Then, before they go up to their seats, he gives them $10 apiece to spend on souvenirs and concessions."

Unlike Pujols, Kline has no special interest in Down Syndrome. But, just like Pujols, he donates his time, name and energy to help out.

"They're good guys," said Sarro.

No, great guys.

With big hearts.

Granddaughter's a rare gem. Opinion by Beverly Beckham, E-mail: bevbeckham@aol.com. July 2, 2003. Reprinted with permission of the Boston Herald.

I will have to apologize to her someday. I will have to tell my grandchild that I cried the day she was born.

Not immediately. Not when I first held her and she looked into my eyes and I looked into hers. There's a picture of this. Lucy, just minutes old, almost saying hello. I never shed a tear in her first 12 hours of her life when I thought she was USDA-approved top-of-the-line perfect Grade A baby girl. Then I was all smiles. I called my friends and said the baby has come. Lucy is here. Lucy is perfect - round cheeks, red lips, downy skin, blond hair, blue eyes.

We joked with her father, "Where are those Sicilian genes?" We hugged one another. We were so lucky. We got our miracle, we exclaimed. And there was no doubt that we had.

And then a doctor walked over to the bed where Lucy lay and he unwrapped her and inspected her. And he said the word test. And then he said Down syndrome.

We cried then. All of us. Instantly. Because what had been perfection just seconds before, what had been all joy and gladness and light, became, with two little words, imperfection and fear.

Stupid, stupid us.

How will I tell Lucy that we wept while holding her? How will I explain that in those first few hours we looked at the gift God created just for us and wanted him to make it a better gift. To fix it. To make our little Lucy just like everyone else. There's been some mistake, God. This isn't what we prayed for.

But isn't it?

Give us a baby to love, we begged and we have her and what sweeter, better, bonnier baby could there be?

People told us that it's only natural to grieve the loss of a dream. And that's what I like to think we did. We dreamed one Lucy, the perfect little girl - like Margaret walking with her mother, like Shiloh on the stage in her toe shoes.

In those first few hours it was this dream that tormented us. And it blinded us, too, because all we could see was what Lucy wouldn't be. Here she was, infinity in our arms, fresh from heaven, in such a hurry to get to us that she arrived two weeks early. And we were judging her.

She left the angels to come here. She gave up paradise for us. And we cried.

Funny thing is she hardly cried. She opened her eyes and took us in, one at a time, and amazingly she didn't seem disappointed at all.

One in 800 babies is born with Down syndrome. The rarer the jewel, the more value it has. That's the way it works with things - with pearls and Lottery tickets and horses and art.

But in our world and in our culture, we like our people to be all the same.

How will I tell her that I wanted her to be just like everyone else? That I was afraid of different when it's what's different that stands out? Are the black sand beaches in Hawaii sad because they're not soft and white? Do four-leaf clovers ache to be three? Does the life that grows above the tundra wish it were rooted in a valley instead?

The red rocks of Utah. Icebergs. The Lone Cyprus. The Grand Canyon. And Lucy Rose.

We expected our life with Lucy to be lived on paved highways with well-marked signs, the rest stops never far from one another.

Lucy is taking us down a different road, a blue highway, instead. It's scary not knowing what's ahead. But no one, even on the wide smooth roads, knows the future.

We yearn for paradise. Lucy just came from there. She is heaven in our arms. We didn't see this with tears in our eyes. But we see it now.

Yoga for the Special Child by Contributing Editor Fernando Pagés Ruiz, E-mail: FpagesJ@aol.com. Yoga Journal, January/February 2003, p. 79-81. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

In a dove-gray colonial house set along a frosty, tree-lined street in Evanston, Illinois, Sonia Sumar prepares for her first yoga student of the day. She lights a stick of rose incense and fits it into a holder on a small altar bearing a statue of Ganesha, the remover of obstacles. She bows and brings her hands together over her brow. Pearl-colored walls, plush amethyst carpeting, and a fanfare of freshly cut narcissus whisper spring on this overcast December morning. The door-bell rings and Sumar unlocks the front entrance. Its low, street-level threshold provides easy access. Paul (not his real name) rolls in smiling, his mother pushing from behind. Sumar takes the handles on his wheel-chair and guides him into the studio. With his mother's help, she lifts Paul out of his chair and lowers him gently onto a yoga mat.

Seven-year-old Paul was born with cerebral palsy. It's very hard for him to relax his body, racked and twisted by muscle tensions he can't control. This morning Sumar supports and guides him into a variety of poses that resemble a spinal twist, forward bend, and Cobra Pose; together they chant Hari Om and practice breathing exercises. Then while Paul lies in Savasana, Sumar massages his feet and his body's relentless tension gives way to a moment of repose. Under Sumar's patient tutelage, Paul has made slow but steady progress in his yoga practice. After almost one year, he can sit up with support and extend his right leg in a modified version of Janu Sirsasana (Head-to-Knee Pose). He can open his hands and bring them together and say Namaste. Every asana is a challenge for Paul; every movement is an advanced pose. Sumar celebrates even a hint of improvement-no matter how small.

Sumar began working with yoga therapeutically in her native Brazil shortly after her second daughter, Roberta, was born with Down syndrome in 1972. Then an elementary school teacher, Sumar had been practicing yoga for several years. Having experienced yoga's benefits, she believed the practice could help her daughter. At first, Sumar massaged Roberta's feet and guided her into very gentle poses. Roberta responded After seeing positive results, Sumar developed a progression of asanas and breathing exercises to foster her daughter's gradual steps forward.

The cornerstone of this program is love, explains Sumar. "These kids progress imperceptibly from day to day; they take a lot of energy. Only love can fuel such a slow and sometimes arduous journey. If you do not love them, you burn out." Sumar works 12 to 14 hours daily and remains as enthusiastic about her students after her last class as she is after her first of the day. If you ask Sumar what she loves about children, she will say, "Everything." If you ask about her favorite students, she'll tell you, "It's the child I'm teaching right now.

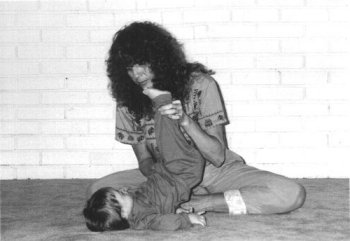

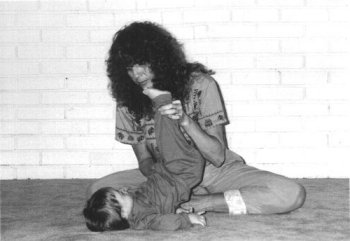

|

| Sonia Sumar with student. |

"These children bring me so much joy because I have to dig deep and grow with them," says Sumar. In many instances she learns as much as she teaches. That's the essence of her approach: Teaching involves more than helping others; it is a means of yoga practice in itself "Many of these children have very advanced souls, much older than you or I," she explains. "They have chosen a very difficult incarnation, during which they can develop spiritually in the most rigorous way. Yoga provides a natural outlet for them because physical and mental disabilities don't hinder spiritual intelligence."

Although her approach is clearly one that is spiritual, Sumar's methods remain firmly grounded in pedagogical science. She structures the evolution of her work with each child on the established pediatric stages of childhood maturation, from early intervention through the inductive, interactive, and imitative phases of development. Over decades of personal experience, Sumar has devised developmentally appropriate sequences for children with various disabilities, including Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, autism, as well as attention deficit disorder. Her work has garnered recognition from Dean Ornish, M.D., author of Dean Ornish's Program for Reversing Heart Disease (Ballantine, 1996) and Bernie Siegel, M.D., author of Love, Medicine, and Miracles (Harper Perennial, 1990), as well as yoga notables like the late Indra Devi and Swami Satchidananda, who had praised Sumar's "service to God's special children."

After Paul's lesson, 9-month old Sara (not her real name) arrives swaddled in a thick ginger-colored blanket. She extends her small arms toward Sumar's face as their features blend nose-to-nose in warm kisses. "The fear of touching in this country is something I can't get used to," says Sumar. "In Brazil no one frowns on affection." Kids need lots of it, and so Sumar never hesitates to shower them with love on every plane. Sara, who was born with Down syndrome, smiles throughout the session. Sumar guides her through an asana sequence that includes supine spinal twists, arm raises, Half-Bow Pose, and inversions. Sara loves to be held upside down so she giggles with pleasure. Toward the class end, Sumar helps Sara become aware of her breathing by placing a tissue in front of her face and asking her to make it flutter as she exhales through her nose. Mimicking a choo-choo train, she unwittingly learns Kapalabhati Pranayama (Purification Breath). During Savasana, Sara falls asleep; after a while, mom tucks her into her blanket and carries her peaceful child home.

But even such joyful relationships, Sumar says, have to be tempered by non-attachment. A note of palpable sadness darkens her tone. From her daughter's untimely death to a recent divorce, Sumar knows the most challenging part of love is letting go. This includes letting go of all of your expectations for a student's achievement. "Expectations lead to disappointments, and your students need your enthusiasm, not your frustration," says Sumar.

So she instructs her teachers-in-training that they need to establish relationships that reach beyond emotional attachment toward a deeper level of spiritual connection. At this level, the sometimes patronizing affection of a teacher matures into the more transcendent love of universal respect-the type of loving that encourages children to evolve at their own pace, even if that pace seems excruciatingly slow. Out-ward signs of progress don't always reflect what goes on inside; Sumar believes her children will use yoga throughout their lives to evolve spiritually.

Sumar also urges her teachers to develop trust in every child's ability to progress. Society has given up on many of these children, but she never makes the same mistake. Not every child is easy to reach, and sometimes the challenges seem formidable. But Sumar says the teachers who do not relinquish hope reap the spiritual reward of patience.

After 30 years, Sumar has not yet grown tired of teaching because she still regards her students as catalysts for her own personal growth. "If I am superficial, I can't reach a child," she explains, "I need to go deep to connect, and this stretches my capabilities, as I am helping my students develop theirs." For those who are close to a child with learning disabilities or work in the teaching profession, Sumar's methods provide an avenue to integrate the paths of spirituality and education-as perhaps they were always meant to be. For more information about Yoga for the Special Child, call (888) 900-YOGA or visit www.SpecialYoga.com.

The Right to an Education by Lizabeth Hall, The Hartford Courant Staff Writer. June 2, 2003, p. 6. Reprint permission granted by Lynne Maston, Permissions Administrator, E-mail: LMaston@courant.com.

He's a 10-year-old boy with Down syndrome. On typical weekdays, his mother takes him to Prudence Crandall Elementary School in Enfield, where he is part of a regular class with his own aide and 23 classmates.

But on June 11, his mother will take him to Superior Court for Juvenile Matters in Rockville, his fourth trip there since Enfield police arrested him Feb. 26. Police charged the fourth-grader with assault and disorderly conduct after the mother of a classmate filed a complaint alleging that he had punched her son in the stomach, leaving a bruise.

He doesn't understand why he has to miss school. As a judge tries to determine if he is competent to stand trial, the 4-foot-2 child sits at a table, chattering to a pocketful of Beanie Babies.

Shadowing his arrest is a conflict over his presence in the classroom. The state has ordered Connecticut's school systems to include more students with mental retardation in regular classrooms, the result of a settlement last year in a class-action lawsuit filed in federal court years earlier.

After the punching incident, school officials suspended the boy for a day, his mother said. When he returned, his teacher had him apologize to his classmate and the two shook hands.

But the injured classmate's mother, Gail Hoffman, said that was not enough. It was the second incident she had reported to school officials, and she wanted the boy removed from the class or his hours restricted. School officials would do neither. They said she could file a school bullying complaint or report it to the police.

She did both.

"I applaud educators' efforts to mainstream these children," Hoffman said. "But my question is, at what cost do they mainstream? This issue is still in its infancy and a lot of parents like myself are becoming concerned. If a child is violent and disruptive, a principal and a superintendent should be able to say more than, 'That's the law and my hands are tied."'

But the child's mother, a local businesswoman whose name is being withheld to protect the boy's identity, fears the arrest will undo some of the gains from the court settlement, namely bringing more children with intellectual disabilities into the educational mainstream.

"I don't want parents frightened and not want their children to be in a regular classroom because they'll think, 'Oh my God. If he does something to another child he will be targeted and he will be arrested,"' she said. "That would be terrible because it is a wonderful experience for their child."

It is also a right the state must enforce as never before.

The state has targeted Enfield and seven other districts in its initial effort to involve more students with intellectual disabilities with non-disabled peers in regular classrooms and extracurricular activities. The others are Bridgeport, Milford, New Haven, Shelton, Waterbury, West Haven and Windham.

The settlement compels the state to comply with the federal Individuals With Disabilities Education Act of 1975, which requires that disabled children be educated in the "least restrictive environment." The law also requires that, when possible and with whatever services are necessary, the environment should be a regular classroom.

State officials acknowledge the challenges of inclusion.

"The step is toward seeing more severely disabled children in neighborhood schools," said Tom Murphy, a state Department of Education spokesman. "With more disabled children, the more challenges there are to the teachers and children in the classroom. Sometimes it can work out very well, because other students learn to accept the child and it helps to make them more understanding and more sensitive. But sometimes it does present quite a challenge."

The key to making it work, advocates say, is commitment.

"Inclusion is wonderful if it is done well," said S. James Rosenfeld, executive director of the Education Law Center, which assists lawyers representing parents of disabled children. "Problems arise when needs and resources outstrip the ability of the professionals in the classroom."

On the February afternoon the Enfield boy was arrested, the child's aide had called in sick and the school system had not arranged for a substitute. The school system has responded by providing more consistent supervision for the child.

Some parents maintain that the school acted inappropriately by leaving him in class. A few parents joined Hoffman in signing a petition, contending that prior episodes of spitting, biting and even throwing a chair made him unfit to be in the all-day class.

"If it wasn't for the law, the child probably would have already been taken out," said Andrea Marcotte, who signed the petition. "If it were my son doing it, they'd have taken him out of that classroom."

Enfield Superintendent of Schools John Gallacher said explaining the law to parents of non-disabled children can be difficult.

"If a child is in special education, they really do have more rights," Gallacher said. "The right of the individual does come in front of the group. I've sat down with parents who are very frustrated, yet that's the way the laws are written."

Advocates find absurd the suggestion that the handicapped are now over-privileged. And they are dumbfounded at the arrest.

"I am appalled," said Margaret Dignoti, president of the Association for Retarded Citizens. "In the 40 years I have worked in the field, I have never heard of such a thing."

Enfield Deputy Police Chief Raymond Bouchard acknowledges that punching and shoving incidents do not usually rise to that. "The level of frustration perhaps was very high," Bouchard said. "Normally, it's left for the children or the parents to work out. This was not the case."

Early on, the disabled boy's mother vowed he would not be cast off in a special-education classroom, segregated from other children because of a congenital defect characterized, in part, by mental retardation.

Even before the settlement, she had armed herself with knowledge of the law and ensured that her son would learn alongside non-disabled students. She has no illusions that he will be a scholar, but he will be able to read, write and comport himself in the everyday world, she said. He has been in a regular classroom since kindergarten, one of a few such children in Enfield.

At the start of the school year, state Education Commissioner Theodore S. Sergi advised public school districts statewide of their responsibility toward mainstreaming intellectually disabled students.

According to the state's most recent figures, 11.7 percent of the approximately 3,600 students in the state diagnosed with mental retardation spend at least 80 percent of their day -- the federal benchmark for inclusion -- with non-disabled students. In 1991, when the lawsuit was filed, the inclusion rate was 9.5 percent.

Across the state, the rate must improve, although the settlement does not specify a numeric goal.

"Right now the assumption is that they shouldn't be educated in a regular class," said David Shaw, the lawyer who represented the plaintiffs in the class-action lawsuit. First, mindsets must change, he said. "The assumption should be that they will be in a regular classroom, studying and not just learning how to tie their shoes or count coins."

Beyond Enfield and the seven other districts targeted for action by the state, another 40 to 50 school districts fall below the statewide average of 37.7 percent for the amount of time students with mental retardation spend with non-disabled students during the school day.

Even those districts that are at the average will have to rethink their approach in many cases.

"We're monitoring everyone in the state," said special education consultant Debbie Richards. "We will continue to work with these eight districts and add more next year."

The education department has allotted $2.15 million over five years to help districts, including hiring two special education consultants, said officials in the special education bureau.

As for the cost, state officials say that it is relative to each district, but that the change need not be more expensive.

Anne Louise Thompson, a special-education consultant to the state, said school systems have been encouraged to redeploy existing staff before investing in new staff.

"Some districts are grasping this," Thompson said. "Others really believe what they're currently doing is appropriate and are resistant to making any changes."

Many school officials see the law's extension to a needier population as yet another unfunded mandate.

David H. Larson, executive director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents, expects it to drive up education costs.

He is one of many educators lobbying Congress to increase the federal government's funding to school systems for special education. He said that between 1990 and 2000, special-education costs in Connecticut rose by $409 million, a 76 percent increase, more than half of which was picked up by local taxpayers.

"A good part of that is we're seeing more severely handicapped children being placed in public schools," Larson added, "and we have had to take on the responsibility for these children."

These educators anticipate parent friction, overwhelmed teachers, added complications and rising costs. Supporters of assimilation worry that school districts will tiptoe around the law.

Even parents of intellectually disabled students are divided over enhanced inclusion. Some oppose it, fearing that school boards will use the law to refuse their children costly individual treatment and services. In regular classrooms, they worry, their children will be bullied and harassed.

Jane Currie has seen inclusion work as both a teacher and as a special education administrator, first in Suffield and now in Farmington. She has been an early supporter of classrooms co-taught by a regular education teacher and a special education teacher.

She distinguishes between a child whose disruptions make it impossible for other children to learn and the child whose disruptions are part of the ebb and flow of adjustment.

"You don't just say one disruption and that's it," Currie said.

The mother of the child with Down syndrome is convinced that had her son not been mentally retarded, the reaction would have been different. Also as the mother of two "normal children," she said she has seen her share of scrapes and bruises left by classmates and never called the police.

"Children with intellectual disabilities are already at a disadvantage," she said. "They shouldn't have to lose out in their education, too."

Father's Journal

Shipshape?

After my annual physical checkup, Emmanuel covered the Band-Aid with my shirtsleeve and declared, "papa is not sick."

|

|

Web Wanderings

Anne Archer, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology at Trent University, Canada, E-mail: aarcher@trentu.ca is conducting an online study of parents' and teachers' experiences with teaching children with Down syndrome. There are two surveys: the first one is for parents and one is for teachers; a third survey is entitled, Stories of Compassion and can be found at: http://www.trentu.ca/academic/psychology/aarcher.

This research has been approved by Trent University's tri-council committee on ethics. All submissions are anonymous.