Dissertation (Spring 2009)

Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama

Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a BMus(Hons) degree at the University of Wales

|

Bethan Mair Pickard Dissertation (Spring 2009) Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama |

Reprinted with the permission of the author. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a BMus(Hons) degree at the University of Wales |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The musical reactions of individuals with Down's syndrome have provided the inspiration and foundation for numerous research studies during the twentieth century, although definitive conclusions on the topic have yet to be reached. Much of the existing research is outdated, referring to a society in a time gone by, when unique and beautiful individuals were sadly segregated from their families and communities and herded together in institutions around the country. This study aims to draw information from past research but also to begin original work in a modern day setting, acknowledging the current situations of people with Down's syndrome.

The steep increase in acceptance and popularity of the music therapy movement in the past thirty years provides ample opportunities for extensive observations of musical behaviour in this valuable therapeutic setting. In addition, a slow but steady increase in provision of instrumental tuition has also bestowed the prospect of analysing the cognitive processes at work when participating in a musical activity. This research project aims to draw together these musical threads in order to present a contemporary review of the subject matter, paving the way for further research in the future.

Chapter 1 comprises both a summary of previous research and an analysis of literature in the field of music and Down's syndrome in the past century, since the initial recognition of the syndrome in 1866 by Dr. Langdon Down. The method, validity and findings of each study are discussed in relation to the paradoxes often found in literature, both popular and professional. Justifications for these contradictions are reviewed, before original research is embarked upon.

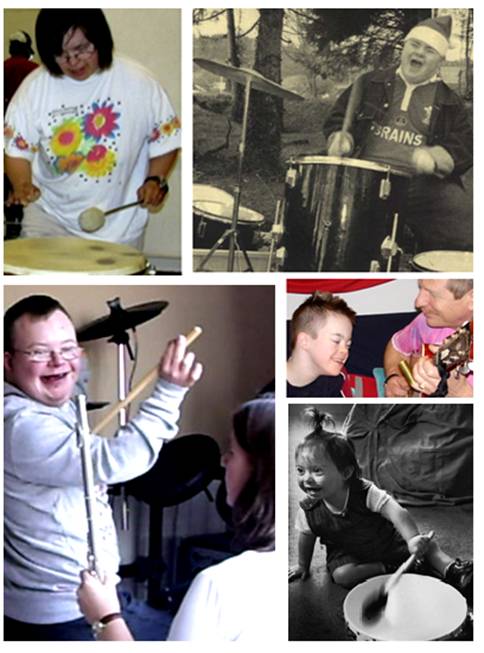

Personal research takes the form of detailed observations of the musical experiences of children and adults with Down's syndrome over the past three months, as well as previous personal experiences. These observations took several varying forms, including music therapy in an adult day centre, outreach music therapy in a client's home, children's group music therapy, peripatetic drum lessons, private piano lessons and a specialist instrumental workshop. These experiences have provided the foundation and substance for my discussions in Chapters 2 and 3; elements within these sessions have been compared and analysed to provide a detailed summary of the musicality of individuals with Down's syndrome in relation to the respective subject areas.

Observations were not limited to a specific geographical domain, for two reasons. Firstly, there was sadly not sufficient provision available in the local area to make adequate observations for this study. Research concluded that Cardiff is unfortunately quite severely behind other British cities in its availability and accessibility of specialist music tuition in this field.1 Therefore, observations were made in Cardiff, Warwick, Birmingham and Manchester. It would appear that Birmingham and Manchester are the epicentres of research and practice in developing and adapting instrumental teaching techniques for children and young people with learning difficulties, namely Down's syndrome.

Rosie Cross, director of the charity 'Melody'2 has made pioneering developments in the field and leads the way forward in inspiring and training a generation of teachers to adapt their methods for the benefit and enjoyment of people with Down's syndrome. Evidence of her success in her endeavours is the recent inclusion of chapters relating specifically to teaching children with learning difficulties in two mainstream high profile music publications.3 Cross's contagious enthusiasm and knowledge is spreading across Birmingham and further afield to Manchester, with the hope of eventually adapting available provision as well as educating teachers all over Britain to provide equal access to musical opportunities for all. It is hoped that this research project will become a stepping stone in providing information and awareness in the field of music and Down's syndrome so that this group of people may be better understood and supported in their musical and non-musical endeavours.

The characteristics of the commonest recognisable learning disability in Britain, Down's syndrome, were first recognised as an entity in 1866 by English doctor, Langdon Down. Although de Waardenburg (1932) initially proposed the hypothesis that Down's syndrome may be the result of a chromosomal abnormality4, the nature of this genetic alteration was not confirmed until 1959, when Jérôme Lejeune established that Down's syndrome is the result of the presence of an extra copy, or trisomy, of chromosome 21. Study of chromosome 21 and Down's syndrome has been at the forefront of human medical genetics since this seminal discovery.5

Most of the research in the field of Down's syndrome concentrates on the physical aspects of the condition: anatomy, genetics, aetiology, general pathology and sociological issues. It is remarkable, and somewhat unfortunate, to find so little research devoted to the “emotional and behavioural aspects” of Down's syndrome.6 One feature of the condition which is referred to again and again, however, is an innate fondness of music:

“It would be difficult to find literature, both popular and professional, on Down's syndrome children which did not make reference to their musical ability in some form or another, yet the scientific literature is surprisingly short on experimental evidence.”7

It is important to note that this characteristic response to music and rhythm, quoted so frequently by other writers, is not mentioned in Langdon Down's original description. He comments only in passing that the subjects he depicts “are regardless of the ordinary circumstances around them, and yield only to the counter-fascination of music.”8

In this introductory chapter I shall discuss the research to date on the musicality and natural aptitude for rhythm portrayed and discussed in people with Down's syndrome, both in professional and popular literature. Much of the description found is closely inter-related and regurgitated without further expansion, suggesting that few of the findings are original. However, the prevalence of this reference may simply be confirmation of this consistent and arguably innate attribute, found in the majority of cases. Perhaps analysing these studies in chronological order will give us some insight into the foundation of this stereotypical cliché.

Fraser and Mitchell (1876) discuss 54 cases of Down's syndrome, which they name “kalmuc idiocy”. In one case study, the authors portray a forty year old woman with Down's syndrome who, amongst many other features of her personality, is said to have been very “fond of music” 9. This article is believed to be the first reference to this frequently quoted characteristic love of music.

Shuttleworth (1900) reiterates these findings, commenting that individuals with Down's syndrome have “a great love of music, their idea of time as well as tune being remarkably able...”10 This may be the first reference to rhythmic proficiency in people with Down's syndrome, a divisive subject which I shall discuss in greater detail in subsequent chapters. However, as consistently found with an abundance of remarks, this comment is not substantiated by any scientific research or empirical studies.

Sherlock (1911) is in agreement with the attribution of rhythmic capability, commenting that “when sufficiently intelligent to be capable of such manifestations” he finds individuals with Down's syndrome to “show an imitativeness and an appreciation of rhythm which are rather striking”11. This observation is much more flattering, certainly than that of Down himself, but more so than Shuttleworth too, in the sense that this statement acknowledges both imitative capacity and “appreciation” of rhythm; thus inferring a degree of competence, talent and sensitivity in a group of people who were at this point in history still deemed uneducable, sub-normal and mentally deficient.

In a more general book entitled Feeblemindedness in Children of School Age, Lapage (1911) makes brief reference to children with Down's syndrome, merely commenting that they are “...little different from other feeble-minded children except that they were more difficult to teach and more fond of music”.12 Given that he made only two remarks on an entire population of children, it is interesting that Lapage felt this fondness of music to be distinct and significant enough to comment upon. In a similarly concise summary, Penrose (1933) comments that individuals with Down's syndrome: “often have a love of music which is rather striking.”13

“All without exception are supersensitive to musical sounds. However low grade they are, all can hum a tune readily from a gramophone correct in note and time.”14

This interesting comment made by Brushfield (1924) was the consequence of an extensive study of 177 children with Down's syndrome, with ages ranging from birth to fourteen years. Possibly the most comprehensive study to date, Brushfield's work gives the most weight yet to the proposition of an innate musical aptitude amongst people with Down's syndrome.

Engler (1949) echoes these findings, commenting on “the surprising ease which many...possess in catching and reproducing a tune correctly.”15 Accurately reproducing a perceived melody is a genuine talent, and one would not expect individuals without any degree of intellectual disability necessarily to be able to complete such a task successfully. This skill is in fact a component of an ABRSM music performance examination.16 Indeed, this superior ability in performing musical tasks promotes individuals with Down's syndrome from being musically inclined in comparison with individuals with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies, to being superior in musical aptitude than the general population, as Schalkwijk suggests:

“Some music therapists, as well as other experts, are of the opinion that...particularly those with Down's syndrome, are very musical rhythmically, even more musical than the non-developmentally disabled.”17

However, this is an area which would seem to require further clarification since making comparisons with the rest of the intellectually disabled community, or with the general population, is inevitably going to generate very different results. The degree, quality and content of musical disposition needs to be elucidated in order to better appreciate, support and understand this group of individuals.

In contrast with the previously complimentary and glowing accounts of outstanding musical competence, Brousseau and Brainerd (1928) are less positive, even derogatory in their observations: “The holding of attention by musical sounds is...purely a response to pleasurable sensation absolutely void of real aesthetic appreciation.” However, they then continue with the over-quoted stereotype found in almost every reference: “Certain points that appear, however, to be common...with few exceptions; fondness of music and rhythmic movements.”18

It would appear that these authors disagree with the level of competence and intelligence that Sherlock (1911) correlates with musical aptitude in Down's syndrome. This could be due to social prejudice and attitudes of inferiority which were deemed acceptable and, more worryingly, correct until relatively recently.

Benda (1947) believed that it was rhythm more so than melody that appealed to individuals with Down's syndrome. He supplemented his comments with the addition of another element, not considered by any previous research on the subject: “Nothing, he says, suggests that they [people with Down's syndrome] have very accurate hearing discrimination.”19 For the first time, a parallel is suggested between auditory perception and this apparent fondness of music; this would later form the basis of Flowers' study: Musical Sound Perception in [Normally Developing] Children and Children with Down's Syndrome (1984), which will be further discussed later in this chapter.20

One of the first studies which based its observations on statistical enquiries was that of Rollin (1946)21, designed to examine the reactions to music of individuals with Down's syndrome. Seventy three residents of an institution whose ages ranged from eight to forty eight years, all with Down's syndrome, were seated in a hall and exposed to dance music, with no initial instruction being given. The facial expressions and body language of the subjects were observed and analysed in order to determine their perceived enjoyment of the musical experience. Rollin commented that “some obviously enjoyed the entertainment” although “none danced spontaneously” and “in not one case was the tempo of the music maintained or brought out.”22 Numerous aspects of this study lack ecological validity, rendering the results unreliable. Firstly, facial expression may not be a dependable measure of perceived enjoyment: the individual could be experiencing intense emotion but failing or choosing not to display it externally. In addition, conditioned behaviour due to living in an institution might cause the participants to refrain from responding freely and expressively to the music.

Moreover, demand characteristics, whereby the participant develops an interpretation of the experiment's purpose and “alter their behaviour in a way that seems to them to be appropriate”23, could limit the validity of the results. Similarly, volunteer effects could produce detrimental consequences for the accuracy of the results, if the participant performs in the way they perceive the examiner to want them to24. This may be of particular relevance in this study, when we consider that eagerness to please and compliance are both commonly acknowledged features of the personality of people with Down's syndrome. These imperfections in the method used deem the results of the study invalid for generalisation.

In addition to providing a detailed and thorough analysis of preceding studies, Blacketer-Simmonds (1953) conducted some original research, with the intention of “tracing the development of the commonly accepted views concerning the emotional and behavioural characteristics” of individuals with Down's syndrome, and “subjecting these views to closer observations than heretofore”.25 The first investigation undertaken had the objective of obtaining information regarding the “temperamental peculiarities”26 of the individuals with Down's syndrome involved, as they had appeared to those who had observed them before admission to Stoke Park Colony, where the author performed his studies.

The results claimed that only 11 out of 140 individuals with Down's syndrome displayed a fondness of music. This may appear to seriously conflict with the aforementioned aptitude and love of music, which touched “all without exception”.27 However, if we look at the methodology for collecting the data which formed the foundation for this study, we will find several unreliable and defective elements. The information collected was not in response to particular questions or categorised in certain subject areas. “Only positive information of a definite nature was recorded, all doubtful or ambiguous statements and inferences being ignored.”28 The author even makes particular reference to the lack of support for the musical character of individuals with Down's syndrome:

“It is perhaps somewhat surprising in how few cases such frequently asserted...characteristics as imitation, love of music and affectionateness were mentioned, though it must be appreciated that the information given was primarily intended to facilitate the admission of the subject to an institution, and unpleasant rather than pleasant traits would therefore quite likely be emphasized.”29

As a result of this predicament and given the incompleteness of the information obtained via the case-histories as shown in the previous study, Blacketer-Simmonds designed a further study where it was decided to make a detailed examination of individual responses of people with Down's syndrome to music under test conditions. Forty two individuals with Down's syndrome were tested, as were a matched control group of forty two individuals with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies.

Part A of the study (General Response to Music) was similar in its format to Rollin's work, and Blacketer-Simmonds too took the facial expressions of his participants as evidence of their perceived enjoyment of the musical experience: “14.3% in each group showed obvious enjoyment of the music in their facial expressions and sustained attention until the music ceased.” Similarly to Rollin's findings, “no spontaneous rhythmic movement or other bodily response was observed in any case”, but equally, no instruction was given.30 Part B (Rhythm) required participants to repeat a rhythmic pattern on a drum, as played by the examiner. The results included the following:

| Down's Syndrome Group | Control Group | |

| “Perfect Performance” | 33.3% | 19% |

| “No sense of rhythm at all” | 57.2 % | 66.7% |

Stratford and Ching (1983) highlight that this test relies heavily on memory, and is the kind of test “given to candidates for examinations for the Royal Colleges of Music”.32 Once again the bar may have been set too high, and the content of the test may be inappropriate for measuring the elements intended.

Part C (Timing) consisted of carrying out exercises, such as marching in line, while keeping time to the music. Instruction was given to that effect.

| Down's syndrome group | Control group | |

| “Good time keepers” | 42.8% | 33.3% |

Part D (Tune) involved encouraging the participants to sing or hum along to popular songs or nursery rhymes. The author comments that this task occurred “without any satisfactory result”. Plenty of noise was produced by both groups, but without any resemblance to the melody. 33

The methodology of Part D may be particularly problematic, since no specific system was employed to measure resemblance of the children's vocalising to the presented melody. Perhaps during in-depth analysis, similarities in rhythm or relative pitches could be found. This could certainly be an area worthy of further research. Blacketer-Simmonds concludes that there were no significant differences in the responses to music and rhythm between the Down's syndrome group and the control group, analytically disproving the extensively cited character trait.

Cantor and Girardeau (1959)34 took a different approach to one aspect of Blacketer-Simmonds' work, investigating rhythmic discrimination in Down's syndrome. Having matched the mental ages of a group of children with Down's syndrome and a group of normally developing children, the authors exposed the subjects to the ticking sound of a metronome, and asked them to describe the rates as “fast” or “slow”.

The normally developing children achieved higher mean scores than those with Down's syndrome, based on the correct number of responses given. Cantor and Girardeau concluded that there was no evidence that supported the description of children with Down's syndrome as having a “marked” sense of rhythm.35 The conditions of this experiment meet a satisfactory criterion of objectivity and the analysis is statistically sound36, thus providing more steadfast evidence than preceding investigations.

Following Blacketer-Simmonds' comprehensive discussion of the field, and Cantor and Girardeau's agreement in challenging the stereotype of a “musical” individual with Down's syndrome, some authors appeared to take note. Eden (1976) is strikingly more cautious with his words:

“...there is a popular impression that all [people with Down's syndrome] are exuberant, happy, biddable and musical. It is probably safer to say that [people with Down's syndrome] are individuals like the rest of us, and are not obliged to be any of these things.”37

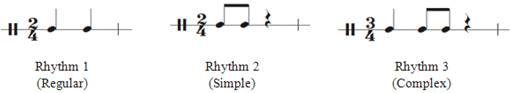

Stratford and Ching (1983) chose to confine their study and experiments to the domains of 'time' and 'intensity'; “the perception of these two elements is interpreted by individuals and presented as rhythmic action”. They excluded two other musical components: harmony and melody; avoiding complications which might have been caused by other variables relating to these factors, such as tempo, pulse, tone, and pitch.38

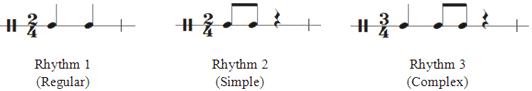

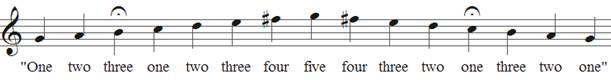

For the first time in all the studies discussed thus far, Stratford and Ching formulate three test groups: ten children with Down's syndrome, ten children with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies, and ten normally developing children; thus addressing the aforementioned dilemma of identifying the test group with which it is most suitable to compare individuals with Down's syndrome in this context. The experiment recorded subjects' responses when asked listen to a rhythmic stimulus and then to tap it on a drum. The rhythms presented were as follows:

|

Half of the Down's syndrome group and half of the normally developing group displayed rhythmic patterns in their responses to the rhythm presented in Rhythm 2, while none of the group with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies were able to maintain a similar rhythmic pattern. Four subjects in the Down's syndrome and normally developing groups maintained some rhythmic pattern in all three performances, while only one of the subjects with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies reached this degree of competence.

The mean scores for the Down's syndrome group and the normally developing group were very close (4.50:4.80), the group with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies achieving a mean score of 2.20. A subsequent Scheffé test showed no significance between the normally developing and Down's syndrome groups, but a significant difference between the group with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies and the two other groups (7.12, P<0.05).39

Though Stratford and Ching are reluctant to make fundamental claims based on the evidence produced in this experiment alone as to whether children with Down's syndrome have a “marked” sense of rhythm, they contradict Cantor and Girardeau (1959)40 in deducing:

“The parsimonious interpretation of the evidence we present must be that there is no apparent difference between Down's syndrome and normally developing children of the same mental age, though a similarly matched group of [children with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies] were significantly weaker in rhythmic ability.”41

Another fascinating detail which this meticulous and accurate measurement technique unearthed, was that “the responses of those who maintained a pattern closely congruent with the stimulus...were all shorter than the stimulus.”42 The authors attributed this discovery to the fact that children of this mental age, although being capable of detecting a rhythmic pattern, were incapable of keeping a similar time span. Although this feature was apparent in all groups, not solely the Down's syndrome group, it may be of relation to behaviours observed in case studies discussed in subsequent chapters. Equally, the fact that “all subjects responded before the stimulus instead of with it; none responded after the stimulus” will be considered and analysed in relation to the responses of other children with Down's syndrome in further case studies.43

In conclusion, Stratford and Ching suggest that at this mental age and level of cognitive development, there is no difference between the rhythmic discrimination of normally developing children and children with Down's syndrome. “Differences lie between [children with Down's syndrome] and [children with intellectual disabilities of other aetiologies] and this comparison could account for the attribution to Down's syndrome children of a higher than normal level of musical skills.”44 This emphasises the argument put forwards previously that the control group used will have enormous bearing on the outcome of a study, and will determine the validity and perspective of findings.

Flowers (1984)45 concentrates on a different aspect of musicality to those previously investigated by Blacketer-Simmonds (1953) and Stratford and Ching (1983), focusing on Musical Sound Perception in [Normally Developing] Children and Children with Down's Syndrome. She states that “little is known...about musical sound perception among children [with] Down's syndrome” and tested the hypothesis that “no significant differences would exist in preference scores of [normally developing] children and Down's syndrome children”.46 The extremes of three categories of musical elements were presented: a) range, b) dynamics and c) rhythm.

The principal conclusion of this detailed study was that children with Down's syndrome preferred music at the piano dynamic significantly more than did normally developing children. This is a fascinating insight which should be applied to make learning, therapy and pastimes more compatible and conducive to the needs of people with Down's syndrome. As Chesney (1980) notes, “if the child dislikes the music used, he may not behave as expected.”47

Further research could also determine whether this finding indicates a distinct dislike of forte dynamic and whether this has hindered the development of people with Down's syndrome in any way. Behaviours demonstrating this possible dislike for loud noise, or confirmed preference of piano dynamic, might have been misconstrued as behavioural problems or could have led to frustration and discomfort for the individual. Flowers (1984) has certainly produced results which are applicable to a wider subject area.

An interesting study to finish this discussion of previous research might be that of Edenfield and Hughes (1991)48, whose aim was to investigate the singing ability of secondary school students with Down's syndrome.

Edenfield and Hughes tested two groups of young people with Down's syndrome, matched for chronological age and IQ: Group One comprising of thirteen students from a school where a choral music education curriculum was established, Group Two consisting of nine students from a nearby school where no such curriculum existed.

| Group One | Group Two | |

| Composite Score | 124.50 | 76.00 |

| Articulation | 26.62 | 15.67 |

| Melodic Rhythm | 10.69 | 5.89 |

| Melodic Contour | 26.46 | 13.33 |

| Steady Beat | 1.77 | 1.00 |

| Pitches Matched | 22.39 | 15.00 |

| Pitches Attempted | 36.62 | 25.11 |

Although the results of Group One are consistently higher, when analysed using the statistical hypothesis tests Mann Whitney U and Chi Square, no significant differences were discovered. Edenfield and Hughes conclude that for this particular sample of secondary school children with Down's syndrome, the training received did not result in statistically significant differences in musical “achievement” as measured by the Singing Assessment, maintaining that “further research is needed to clarify specific traits and needs related to the development of singing ability in students with Down syndrome.”49

This study supports the notion that any musical aptitude found within the Down's syndrome community is not necessarily taught or learned, and is far more likely to be innate. Although previous research has found itself to be abundantly disproving this theory, the ancient clichés are still quoted to this day:

“Even people with little or no acquaintance of Down's syndrome will, if the conversation turns in this direction, respond with a remark concerning their supposed love of music.”50

As this overview of literature reveals, during the twentieth century, numerous studies have aspired to account for the label given to individuals with Down's syndrome of being “particularly responsive to music... able to play in tempo [and] rhythmically skilled”51. There appears to be a paradox between these frequently asserted claims and the outcomes of any empirical research; to date there has been no conclusive evidence which justifies the origin of this characterisation. Through original research in the form of various case studies I intend to investigate the musical experiences of children and adults with Down's syndrome, with the objective of discovering any innate musical potential and analysing the form of this expression. I shall focus on rhythmic elements in order to develop some of the theories already proposed and discussed in this chapter, but also the treatment of instruments which articulate rhythmic expression, and the cognitive process which is integral to learning and expressing musical ideas.

Following on from the focus in the aforementioned studies, commenting upon “an appreciation of rhythm which [is] rather striking”52, I shall discuss in this chapter the rhythmic characteristics consistently presented throughout my observations in various locations and settings. It should be noted that the individuals discussed within the given examples range from toddlers to old age pensioners, and could be living in Cardiff, Manchester, Birmingham or Warwick; supporting the notion that rhythmic characteristics are similar if not identical throughout the Down's syndrome population.

During an outreach music therapy session with a teenage boy with Down's syndrome, a sense of “imitativeness” is well represented. The participant, G, enjoys hearing his name in the welcoming 'Hello Song' and very early into the session he begins to beat on his drum kit the basic rhythm of the song. D, the music therapist, notices this and supports his beating, keeping this rhythm in her left hand while adapting her singing and the melodious playing of her right hand. G continues to enjoy the rhythm he is mirroring, and D eventually alters her part slightly, leaving G to play this rhythm independently.

Probably without realising, G had learned a fairly complex rhythm in a compound time signature, and by concentrating on the rhythmic sequence was holding the sticks more firmly and tapping the drum with more control and intent; improving his fine motor skills. This supports Ockleford's observation that “Pupils' motor abilities and performance skills may develop hand in hand – each potentially benefiting from the other.”53

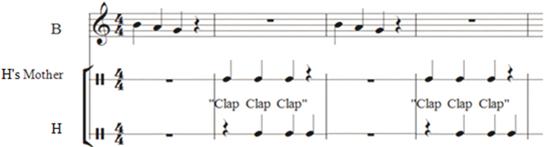

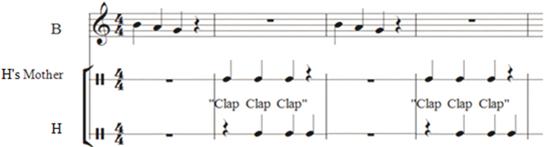

|

The constancy of G's imitativeness continues, as D musically adds a slight ritardando

as she reaches a cadence point; G too slows and hits a chord with both sticks

on the resolution of the cadence, emphasising his awareness of both musical

structure and practice.

Very similar behaviour is witnessed with J, a man in his early twenties with Down's syndrome, at an adult day centre. J is very receptive to D's playing, and their musical improvisation concurrently comes to its natural end, both melodically and rhythmically attuned. J was deep in concentration as they finished their piece, and was silent for a few seconds before he looked up and smiled at D. Similar to G's epic crash on the final note of the improvisation, this is another example of appreciating and imitating performance etiquette; as though J understands his role in a musical context, perhaps from concerts he has attended or watched on television.54

When C, H and F, three seven-year-old boys with Down's syndrome, are invited to play the drum in front of the assembled music therapy group, accompanied by the music therapist, B, on the piano, all three eagerly accept. H begins by playing rhythmically but his beat bears no apparent resemblance to that of the piano accompaniment which was established before he began. However, B expertly adapts her piano part so that it reflects and complements H's beating of the drum. Once this initial adaption has been made, H retains a steady, unwavering pulse and his focus turns to B's hands at the piano. He studies them with deliberate concentration, perhaps watching for the slightest change of nuance or rhythm, which he expertly mirrors.55 Identically to G and J, H anticipates the cadence point and musically incorporates it into his improvisation.

Having observed that G, J and H's interpretations of cadence points were all very similar, strengthening the argument for an innate “love of music...”56 and a “rather striking”57 sense of rhythm amongst individuals with Down's syndrome; C's and F's improvisations demonstrate the individual differences and unique aspects of musical interpretation, which are logically equally apparent within this group of people as in the general population. It is imperative to keep sight of individuality within generalisation, and although these findings may advocate the age old stereotype, unique contributions and characteristics must be noted and appreciated.

“Although the responses of children of similar pathologies may resemble each other the musical self-portrait is highly individualized. No two children react exactly alike and responses can never be predicted.”58

F's drum beating is equally revealing but very different in several ways to that of H. F beats quickly and furiously at the drum, looking surprised by his efforts at one point, as though his arms don't belong to him. F displayed signs of hyperactivity and frustration prior to this performance, suggesting that this opportunity may have provided the required expressive outlet where he could share feelings in a supportive environment59. Oswald describes this unburdening release of emotions in the context of the security offered within the structure of the session: “The musical [therapeutic] experience allows us simultaneously to have very strong emotions and to safely contain these emotions in a non-disruptive way.”60 Bunt comments that according to psychoanalytical theory “A musical composition such as an improvisation is an acceptable form in which we can expose some of our wilder and more out-of-control feelings.”61

C begins to play with a hard and constant beat. Once again, his pulse bears no resemblance to what is unfolding in the piano part, but B proficiently switches to C's beat, accommodating and supporting him. C produced some very controlled accelerandi and ritardandi, and was very involved in his music: he accidentally hit himself on the chin and even hit his glasses with the sticks several times. Similar to when this happened to G in a previous session, this didn't deter him, confirming the total involvement and appreciation people with Down's syndrome display when involved in a musical activity.

When C's beating reached a truly furious state, yet all the while very rhythmic, B introduced some dissonances in the piano part to mirror or perhaps release the tension in the wild, passionate rhythms. C competently sensed the approaching cadence even within the disguise of relatively extreme dissonances and on sounding the final note threw down his sticks and ran back to his mother's arms, full of smiles and pride at his accomplishment. C's brother K, who doesn't have Down's syndrome, takes a turn after his brother and intriguingly isn't as rhythmic in his playing. This would appear to eliminate or at least dispute the potential of C's musicality being hereditary, although factors such as K's age and levels of musical exposure might contest this conclusion.

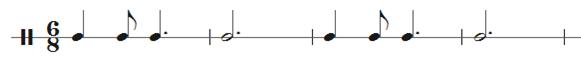

A music workshop for young people with intellectual disabilities in Manchester provided a prime opportunity for observing rhythmic tendencies within a group clapping game. The leader, P, claps a simple rhythm which the group claps back to her in reply. P occasionally amends the rhythm slightly, challenging the group to keep up with the evolving pattern. The group consisted of parents, siblings, musicians, group leaders and eleven young people with intellectual disabilities, eight of which were girls with Down's syndrome.

The general impression of the group reply to P's rhythmic 'question' is neither tidy nor together. The musicians and family members involved keep the rhythmic structure in place while the participants with intellectual disabilities, particularly those with Down's syndrome it would appear, seem to lag significantly behind.

Observing individual participants in turn, the reproduction of the rhythmic sequence is relatively accurate; it is the placing of this response in relation to the question which causes the subsequent delay. In fact, the majority of the eight participants with Down's syndrome appear to be fairly accurately constructing the rhythm, but with each of them beginning the response at a slightly different rhythmically 'incorrect' juncture, rendering the overall effect to be muddled and rather chaotic.62 The rhythmic conversation between a single participant and P could be notated as such:

|

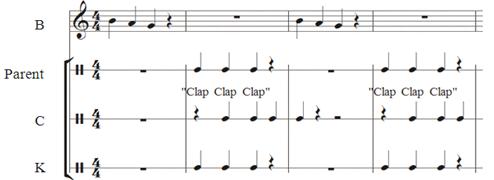

The superimposition of the similar responses of other participants upon this conversation demonstrates the hectic spiral and confusion resulting from misplaced rhythmic responses:

|

It is interesting to note that a very similar feature is commented upon by Stratford and Ching (1983), whereby “the responses of those who maintained a pattern closely congruent with the stimulus...were all shorter than the stimulus.”64 Therefore, although the rhythmic pattern produced by participants may have been similar to that of the stimulus, its reproduction was deemed inaccurate when measured in relation with a constant beat. Stratford and Ching (1983) deduced that “although children of these mental ages whilst being capable of detecting a rhythmic pattern, were incapable of keeping a similar time span.”65 It is also worth mentioning that in the study of Stratford and Ching (1983), all the participants “responded before the stimulus, instead of with it; none responded after the stimulus”66.

In the 'copying' segment of G's outreach music therapy session he would mirror D's sequences on the drums, but was constantly early, eager to jump in with his response and apparently unwilling or unable to wait for the following distinct measure of a bar67, echoing the findings of Stratford and Ching (1983). In a similar 'copying' exercise with D, J would clap D's rhythm back to her before she had even finished her first rendition; he was keen to clap in time with D, perhaps feeling a connection and sense of acceptance in so doing.68 Nordoff and Robbins report a similar excitement in a young boy with Down's syndrome during music therapy:

“He enjoys the musical give-and-take and anticipates the next working session. His musical intelligence is realised gradually and the intimate rapport consolidates the work. A musical companionship arises which makes further therapeutic coactivity possible.”69

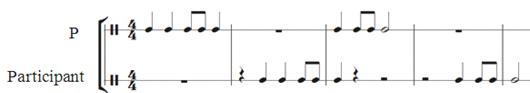

|

This rhythmic characteristic is replicated once again in the group music therapy session, where C, H and F adhere to a similar inclination. H appears to have the most developed understanding of the task at hand and always beats the tambourine the required three times, yet always begins either a beat early or several beats late, despite his intense concentration and effort, and the patient encouragement of his mother.

|

C's brother K provides another intriguing insight when he joins in this exercise with C:

|

K succeeds in accurately producing the intended rhythmic sequence while C adheres to the aforementioned rhythmic predisposition found in people with Down's syndrome. C's superior musicality and sense of rhythm plays no part in the precise execution of this task. It is possible, if not probable, that this inconsistency in desired outcome between various tasks and the identification of this specific element which challenges people with Down's syndrome, could account for the contradicting paradoxes often reported between scientific findings and descriptive literature. This inconsistency could justify the deficiency of conclusive evidence regarding rhythmic ability in people with Down's syndrome; inclusion and consideration of this discovery in future research could resolve the discrepancy, thus generating more accurate and significant results.

This tendency for accurate reproduction of a rhythm presented at inaccurate points of a musical sequence is an extremely prominent feature in all the observation work undertaken, perhaps the single most prevalent trait witnessed. Further research would be required to ascertain an explanation for this ostensible delay in reaction; a possible line of investigation would be whether there is a link between the delay many children with Down's syndrome experience both in initially developing speech70, and once sufficient speech is acquired, in eventually formulating a response when presented with a verbal cue71. Musical conversation is potentially reflecting verbal communication, and this discovery could be used in turn as a resource for supporting speech acquisition and communicative competence.

With the intention of further contextualising, this chapter focuses on the innovative and exciting teaching methods which were experienced while completing o bservations for this study.72 This is a subject area which was not addressed in research completed during the twentieth century since children with Down's syndrome would rarely if ever have been considered capable of receiving instrumental tuition. Fortunately, this mentality is gradually changing and a handful of dedicated and compassionate professionals are leading the way for inclusion in this area. One would sincerely hope that this is an area which will develop considerably over the coming years.

Four teaching methods will be referred to, encountered in three private piano lessons and one peripatetic drum lesson.73 The variety of methods used reflects the diversity that exists amongst individuals with Down's syndrome, “to an extent similar to that seen in the non-disabled population”74. As Selowitz concisely comments, “There are more differences between children with Down's syndrome than there are similarities.”75 It would be naïve to expect all children to respond consistently well to one method of instrumental teaching; this supposition applies equally to children with Down's syndrome.

The purpose of this study is most certainly not to establish a 'Down's Syndrome Teaching Method', but rather to acknowledge a variety of methods which have been successful, and distinguish which aspects of these approaches could be further implemented in instrumental teaching, general musical experiences and perhaps even in a more widespread application to compliment other facets of everyday life.

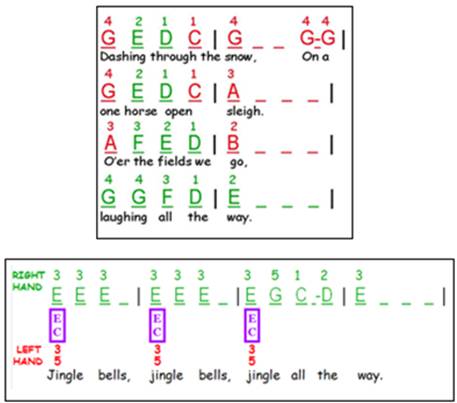

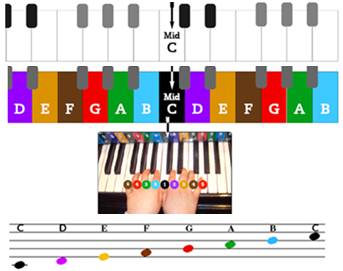

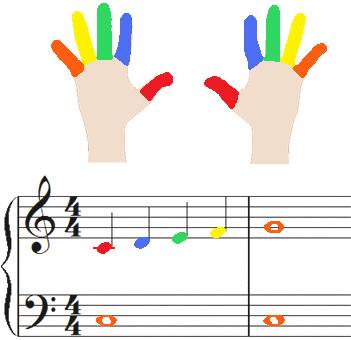

The first method is that of Rosie Cross, who is an accomplished and experienced teacher of young people with Down's syndrome in Birmingham.76 Cross discusses several alternative notation resources appropriate for musicians with Down's syndrome, such as the 'Letter in Note' system and Alpha Notation:77

|

|

However, in specific relation to the teaching of T, a young man with Down's syndrome, Cross doesn't utilise either of these notated methods, deciding early on that “T was never going to be able to read notation and so another way had to be found of enabling him to access music and internalise it.”79 Learning by rote was established as a way for T to commit to memory some well-known melodies in order that he may progress at a similar pace to his siblings. This small consideration is in fact very significant when dealing with children with Down's syndrome; Cross notes that it was important for T to “perceive himself to be taking part in the same activities as his siblings.”80

Other methods employed included pointing to or even playing over T's fingers, in order for him to discover the correct physical movements and sensations required. This was an aspect of the lesson that T's musical mother was able to replicate during practice sessions at home, discovering that “putting her fingers over his and 'playing' his fingers helped him towards eventual independence.”81

|

Cross explains her choice of teaching method in this instance, encompassing all the smaller techniques discussed, referring to improvisation as a preference when working with young people with an intellectual disability:

“I believe that for those with a learning difficulty, the key to successful playing on any instrument lies in improvisation. It encourages free creative expression; it does not depend on written notation; it can be adapted to suit a pupil of any ability and allows the pupil to take charge of his own learning as you develop this type of playing together.”82

The exploration of improvisation provided the foundation for T's development over a decade of piano lessons. Images in tutor books might provide ideas for an improvisation, so that T can see a parallel in his own development and in the more conventional teaching styles received by his siblings. Equally, inspiration might be drawn from a popular tune or a current topic, such as the festive season or the weather. Improvisation can also be used as a “powerful and valid means of communicating emotion and feeling with the outside world for people with learning disabilities”83, allowing a piano lesson to also become a welcome outlet for expression and emotional development.

|

A significant demonstration of the power of T's improvisations came at an annual 'Melody' concert in 1998. As T improvised on the stage in front of the gathered audience, a toddler who had previously been misbehaving and running around during the performances climbed to the stage and sat beside T.

|

The young boy sits beside T, smiling happily, for nearly three minutes while T performs his improvisation. Not once does the toddler interrupt or make any attempt to touch the piano; he is enthralled by T's performance. Although Cross mentions that T's mother was “obviously not expecting him to be a concert pianist”84 when he began his tuition, this level of musical interaction and the depth of impact T has upon his audience would rival many a professional performer. Improvisation made music accessible and enjoyable for T, and parallels between his musical development and his daily life became evident, as Cross explains:

“...it began to be obvious that there were benefits to his everyday life which were a direct result of his piano playing. His motor co-ordination improved...suddenly he could handle a knife and fork and do up his shoe laces. His speech improved because he was learning to listen in a concentrated way. The work we were doing on the piano helped to address numeracy and literacy and his self confidence as he discovered that there was something he could do well.”85

The second approach I shall discuss is that of Michael Maxwell Steer, which was utilised with W, a young woman with Down's syndrome. Steer introduces his style of teaching, placing particular emphasis on the individuality of each pupil:

“As a composer I'm very much aware of the 'symphony' of idioms that now surround us. As a piano teacher it's my job to work out which of the available idioms means most to an individual student and guide her/him gently in the direction which will have most meaning.”86

This holistic and patient approach is highly suitable and attractive for children with learning difficulties, including those with Down's syndrome.

|

|

Similar to Cross, Steer had no previous experience of teaching pupils with Down's syndrome until he met W, who already had an electric keyboard with a coloured lighting system, to which she responded well. Steer adapted a key chart based system he entitled 'Colour Muse', which had previously been successful with an autistic pupil, to supplement W's keyboard. The adaption was a great success and has enabled W to progress to an acoustic piano and to more demanding and rewarding repertoire.

|

The 'Colour Muse' approach combines the colouring of the notes of the piano with coloured note heads on the stave, thus encouraging a clearer connection between notated music and the instrument, and a better understanding of the products of this relationship. The theory behind this innovative approach stems from a decade of research, founded in the discovery that colour and shape are processed in different parts of the brain87 and thus colour recognition bypasses the need for decoding complex information from a single colour.

“By reducing the density of black information for beginners the whole process of brain-hand coordination seems to develop faster. Even with able children coloured notes accelerate the prioritisation of both visual and 'handed' information much better than black notation.”88

An additional ethic behind the 'Colour Muse' philosophy is that of giving concerts as opposed to attending formal examinations. This element is of particular relevance to pupils with Down's syndrome since the strict formality and criteria of an official examination may undermine the personal achievement attained. Dr. John Diamond refers to the detrimental effect that strict musical training can have upon an innate love of music:

“Every child starts with an exuberant open-hearted love of music. Gradually and tragically this is destroyed by the horrors of most musical training systems.”89

Cross supports a similar philosophy, suggesting that performance rather than examination may be the way forward for pupils with Down's syndrome. Steer expands on this performance ethic:

“In the system I have evolved, each performer's progress is defined by his/her self. What s/he discovers in/by performance is authentically his/her own inner 'meaning/s', or sense of self-worth - which I consider the greatest form of empowerment any education can offer. In contrast, the conventional way of learning a musical instrument brings you into contact primarily with the defined aesthetic parameters of a range of 'approved meanings'.”90

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music offers a 'Performance Assessment Test' to those for whom the graded examinations are “unsuitable”91. The ABRSM describes this assessment as:

“an opportunity for musicians of all levels to have their prepared work assessed by a professional musician, without the pressure normally associated with public performance or exams. There is no pass or fail to worry about and no marks are awarded, just constructive comments on the performance written by the examiner onto the certificate that each candidate receives at the end of the assessment.”92

From personal experience, I have found this qualification to be an excellent provision, granting a sibling with Down's syndrome access to an identical experience of a musical examination to her sister. It could be argued that undergoing the nerves and exhilaration on the day of an examination is an experience that an individual shouldn't be refused on the grounds of disability. In addition, having already stressed how admiration of a sibling is characteristic in Down's syndrome93, any provision that aims to facilitate equal opportunities for siblings, regardless of their intellectual disability, must be highly regarded.

|

The third observation I shall refer to is that of a private piano lesson in Cardiff. R, a teenager with Down's syndrome, has been studying piano with the same teacher for several years but is still acquiring new skills each week, developing at his own pace.94

A much more conventional method is employed during this session, a selection of standard beginner tutor books are used as well as unchanged standard notation. The teacher, Judith Shewring, begins the session by asking R to find all the “C notes” on the piano. He does so proficiently, suggesting that he has totally understood the association between the shaped note heads on their respective staves and their placement upon the keyboard.95

R follows this with a scale of C major which he plays at a slow tempo, but with great precision and meticulous finger movements.96 Shewring watches attentively, replying with enormous patience and kind, heartfelt support: “Were you happy with that?” R eloquently replies: “I'm very pleased.” Such a simple sentiment is often disregarded in a conventional lesson, in which the pupil may even be frowned upon for playing incorrectly, and deduction of satisfaction with their own effort is rarely if ever addressed.

An element which is often a central feature of music therapy sessions was equally prominent in this compassionate piano lesson: Shewring puts great emphasis upon the element of choice. As 'The Mouse' is opened in front of R, she asks whether he would like to play with both hands or just the one, and whether he would like her to play through the piece first or whether R would like to begin. R chooses to begin himself and decides to perform the melody with his right hand. This power of decision granted to R means that he can determine the content and direction of the session, working at his own pace, and affords him a degree of responsibility and independence in his teenage years.

|

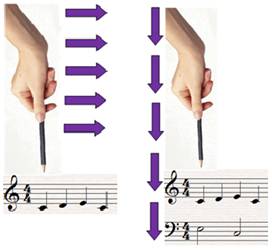

Shewring employs some similar devices to Cross, such as pointing to the notes as R reads them97, as seen in Figure 16. R's developed ability to read notated music employing both hands requires Shewring to adapt the pointing method a little, with a different motion when notes are sounded with a single hand or played as a chord. When there is a single line melody in the right hand for example, Shewring follows the line in a horizontal direction with the pencil. However, when a chord appears and both hands are required to play concurrently, she follows the chord down the page, ensuring R reads and subsequently plays the notes on both staves before he moves on. This method appears to be very effective, and R doesn't miss a single chord.

|

Shewring has a wonderfully patient and sensitive manner, encouraging R in all he does. This sincerity has certainly facilitated R's developed technique and proficient sight reading skills. Returning to the exercise that began this lesson, Shewring fascinatingly comments that R has a great love of scales.98 Scales are interspersed throughout the lesson, providing a welcome break from the highly concentrated task of reading music. Shewring teaches scales by rote, incorporating finger patterns as she introduces them.

|

Shewring approaches G major in this lesson and begins by commenting that this scale has one of the “special” notes99 in it, as she sounds the F# key on the piano. When asked if he can name the note, R promptly replies “F sharp”, to which Shewring offers genuine congratulations, without seeming condescending. Shewring then goes on to play the scale in front of R, for him to both hear and see the necessary sequence. As she plays, she sings the number of the appropriate finger to use for each degree of the scale, pausing to reflect and accommodate the thumb movement that R needs more time to facilitate.

|

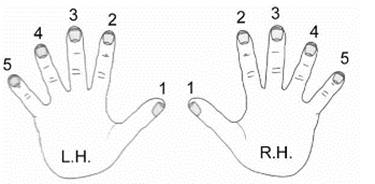

R has internalised the importance of finger patterns, perhaps due to the emphasis Shewring rightly places upon them. This is certainly a demand that would be made of a non-disabled pupil, and was one of the frustrating aspects of piano training which eventually led to the termination of my own piano lessons. Further demonstrations of R's thorough comprehension of fingering can be seen when in performing a piece he plays an E in the left hand by mistake, using finger L.H. 3100, and corrects the mistake by moving to a C, but also changes to use finger L.H. 5101. On another occasion, when asked to play in turn all the “F sharp” notes on the piano, R uses his right hand for the notes above middle C102 and finger L.H. 4 for all the notes below middle C. The index finger is normally used for indiscriminate pointing103, however R chose L.H.4, which would be the correct finger to use for this note in such scales as E, B and F# major.

If children with learning difficulties, perhaps more-so those with dyslexia or dyscalculia104 have trouble with numbers, there is an alternative approach to Shewring's effective insistence upon correctly numbered fingering, which labels each finger with a colour rather than a number.105 This differs from Steers' method since it is the finger and not the note that corresponds to the colour.

|

Such simple adaptations to conventional methods allow a diverse cross-section of society, whose desire for musical fulfilment would otherwise be ignored, to access the enjoyment and rewards of a musical education, as well as the powerful emotional experience of expressing oneself through an instrument.

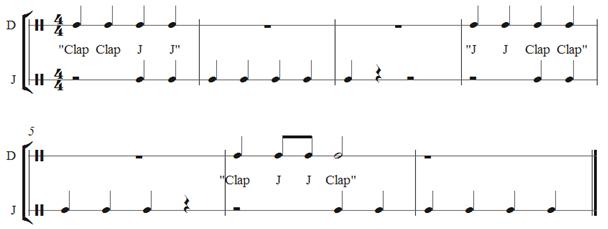

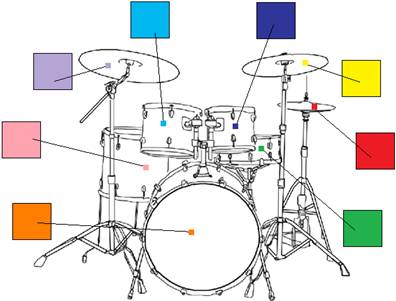

The fourth and final lesson I shall comment upon is a peripatetic drum lesson with A in Warwick. Although technique and use of notation vary almost immeasurably between the drum kit and piano, the innovative and creative use of colours was included in this lesson as it was in those of Steer, and those discussed by Hopson (see Figure 20).

As A excitedly collects his drum sticks from his music bag, his teacher Seth Harris-White prepares the drum kit for the lesson, attaching coloured patches to the various components which make up the instrument. Harris-White is careful to select the appropriate colour for each drum, and has to double check with A which shade of blue corresponds with which of the 'toms'.

|

In the same way that the 'Colour Muse' method corresponds coloured patches on the piano keys to coloured note heads on the stave, Harris-White has developed a method whereby the coloured patches on the particular drums correspond to the specific notated rhythmic patterns referred to. Due to the nature of untuned percussion instruments such as the drum kit, the placement of the note head does not correspond with a pitch; alternatively, the placement on the stave refers to which specific component of the instrument A is to sound the rhythmic pattern upon.

A is therefore reading conventional drum kit notation, but instead of solely reading the placement of the note head on the stave in order to decide which instrument to sound, the addition of colour is supplementing this cognitive process.107

|

The progress A has made in the short year he has been learning the drums is testament to the success of Harris-White's creative method109, and is evidence that this kind of adaptation can assist children with Down's syndrome to access instrumental tuition upon the instrument of their choice and to develop at a similar rate to siblings and peers. Publication of such a method as well as increased awareness of these adaptations and their success rates would further promote the philosophy that any child is capable of learning a musical instrument, and shouldn't be denied this wish solely on the grounds of prejudice against their genetic make-up or assumptions made about their capabilities due to a degree of intellectual disability. In support of alternative and practical approaches when teaching children with learning difficulties, Ockleford comments:

“By far the most powerful way to teach music to those with learning difficulties, is through using music, rather than talking about it! Using language just erects an unnecessary barrier: for many pupils music offers a far more immediate form of communication in sound.”110

Another method which has been referred to several times in discussions with parents of children with Down's syndrome is the Suzuki method.111 The philosophy behind Suzuki is not to produce world class performers: “The benefit of studying music, to Suzuki, was an increase in sensitivity and understanding that would lead to a better, more enriched life.”112

This holistic philosophy is very fitting when considering children with Down's syndrome who are both susceptible to and interested in music. A central ethos of the Suzuki approach is that every child can succeed given the right environment: Gowers comments that her pupil with Down's syndrome was a “shining example” of this philosophy, developing a “remarkable feeling for nuance and phrasing” and making slow but sure progression since initial struggles with technique and rhythm.113

|

Using a love of music to develop other skills through this method would appear to incorporate several of the benefits of music therapy, instrumental teaching and natural musicality in one inclusive approach.

A culmination of the most successful elements in all these fascinating approaches might produce an entire methodology which could be promoted in the musical education of people with Down's syndrome. However, keeping in mind the uniqueness of each individual, any combination or minute detail which relates to and ignites interest and enthusiasm in a specific person should be acknowledged, appreciated and applauded.

During the twentieth century, extensive research was completed with the intention of presenting scientific evidence and thus justification for the labels of “musical” and “rhythmic” given to an entire population of people with Down's syndrome114. Much of the work was inconclusive due to restrictive methods lacking ecological validity, and the remainder seemed to disprove the label: Blacketer-Simmonds (1953) concludes that there were “no significant differences” in the responses to music and rhythm between the Down's syndrome group and the control group, analytically disproving the extensively cited character trait115, while Cantor and Girardeau (1959) claim that there was no evidence that supported the description of children with Down's syndrome as having a “marked” sense of rhythm. 116

In order to take into consideration the outdated nature of previous research and the long-awaited transformation of the role of individuals with intellectual disability in today's society, original research was embarked upon in the form of observation work in a variety of settings and geographical locations. These observations presented a diverse representation of the musical experiences of people with Down's syndrome of all ages (both male and female). The potential for conducting a study in so many musical settings is a welcome example of the many opportunities now available to people with Down's syndrome, compared to the sheltered and uniform existence within an institution where most previous research was performed.

Conclusions drawn from the work focused on two areas: rhythmic perception and instrumental teaching. Firstly, developing the preceding concentration upon rhythmic elements of musicality, it was discovered that individuals with Down's syndrome were capable of very accurately reproducing a rhythmic sequence but the placement of this reproduction was much less precise. A group game of rhythmic question and answer demonstrated the inability of the participants with Down's syndrome to correctly place their response in order to form a rhythmic pattern or conversation between both parts.

Despite this, when observing each participant in turn it was ascertained that each was in fact accurately producing the rhythmic motif, merely beginning it at a non-rhythmic juncture within the structure of the pulse. The overall effect was of incoherent clapping and little rhythmic interest was discernable; however, were the measuring system of Stratford and Ching (1983) employed in this instance, the results would undoubtedly show the timings between each clap produced a precise replica of the initial rhythmic stimulus.

|

| Rhythm 1 | Rhythm 2 | Rhythm 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

0.7961 0.8303 0.8607 0.88255 0.87685 0.80655 0.8303 0.86165 0.82365 |

0.0912 0.90345 0.10735 0.8417 0.11495 0.931 0.13585 0.8968 0.11305 0.90345 0.11875 0.84075 0.11495 0.95855 0.12825 |

0.70775 0.08645 1.15805 0.59755 0.09405 1.18655 0.63555 0.07315 1.0051 0.61085 0.09785 1.0355 0.62225 0.08075 |

The finding that participants with Down's syndrome can accurately reproduce a rhythmic stimulus but cannot precisely place it in correct relation to a constant pulse confirms a marked and striking sense of rhythm within the Down's syndrome population, but explains why the methods previously utilised have failed to reach the same conclusion. Further research should certainly take this breakthrough into account, and plan its approach accordingly in order to accommodate this discovery and thus produce more significant and informative conclusions. Subsequently, the reason for this very specific trait in rhythmic reproduction could be analysed and should a reason be found, this could be incorporated and tackled in musical tuition in order that people with Down's syndrome may eventually be able to celebrate and enjoy their marked rhythmic ability in a group setting without the hindrance of the current misplacement.

This suggestion follows on to the second area of research: instrumental teaching. The beginning of this study concentrated upon research in a time where individuals with learning difficulties or intellectual disabilities were considered inferior and referred to as subnormal and defective. Unsurprisingly, during these times children with Down's syndrome were not welcome to instrumental tuition or a formal music education, and consequently there is little available information upon the subject of instrumental teaching and the most suitable and successful method for people with Down's syndrome.

Long-awaited advances in this field were discussed, with reference to the refreshing and pioneering approaches of Cross, Steer, Shewring and Harris-White. Strategies of particular interest and success were noted, with particular reference to alternative methods of notation, since this is a portion of music education which might present the greatest challenge to those with Down's syndrome.

It was concluded that the combination of a patient and flexible teacher, and the contemporary advances in original and innovative techniques provide the opportunity for any child, with or without any degree of intellectual disability, to access the fulfilment and pleasure of performing music. This accomplishment encompasses varying forms, such as the eventual understanding of a particular phrase through dedicated practice with a devoted parent at home, performance of a short piece to one's parent at the end of an intensive private lesson or a creative improvisation in a public concert.

In order to further the efforts of these devoted teachers, the methods developed need to become more accessible and widespread in their availability, perhaps via publication or promotion. In addition, the next generation as well as all preceding generations of music teachers need to be made aware of the potential of students with learning difficulties. As long as teachers are open to adapting their methods in order to provide for a wider cross-section of today's society, there is very little training or adjustment required118. Most dedicated instrumental teachers already have the capabilities within them to teach a student with Down's syndrome, as long as they are willing to open their minds and their hearts to a new possibility.

The underlying message of this study is that individuals with Down's syndrome should be valued and appreciated for their unique and beautiful qualities, deserving not to be underestimated on the grounds of ignorant, misinformed prejudice. Revelations regarding rhythmic capabilities and tendencies should be noted and incorporated into future research and teaching approaches, thus providing appropriate provision for a particularly musically inclined group of individuals within our communities.

|

Achenbach, C., Creative Music in Group Work, Winslow Press Ltd, Oxon, 1997

Alvin, J., Music for the Handicapped Child, Oxford University Press, London, 1976

Alvin, J., Music Therapy, Stainer and Bell, London, 1966

Bailey, P., They Can Make Music, Oxford University Press, London, 1973

Bancroft, D. and Carr, R. (eds.), Influencing Children's Development, Blackwell, Oxford, 1995

Bird, G., Alton, S. & Mackinnon, C., Accessing the Curriculum – Strategies for Differentiation for Pupils with Down Syndrome, Down Syndrome Educational Trust, 2000

Brindle, R. S., Contemporary Percussion, Oxford University Press, London, 1970

Bunt, L., Music Therapy: An Art Beyond Words, Routledge, London, 1994

Carr, J., Down's Syndrome: Children Growing Up, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995

Coll, H. & Finney, J. (Eds.), Ways Into Music – Making Every Child's Music Matter, The National Association of Music Educators, Matlock, 2007

Dessent, T., Making the Ordinary School Special, The Falmer Press, East Sussex, 1987

Dobbs, J. P. B., The Slow Learner and Music: A Handbook for Teachers, Oxford University Press, London, 1966

Eden, D. J., Mental Handicap – An Introduction, G. Allen and Unwin, London, 1976

Gaston, E. T. (ed.), Music in Therapy, Collier Macmillan, London, 1968

Gulliford, R. & Upton, G. (ed.), Special Educational Needs, Routledge, London, 1992

Hassold, T. J. & Patterson, D. (ed.), Down Syndrome: A Promising Future, Together, John Wiley-Liss, New York, 1999

Hayes, N., Doing Psychological Research – Gathering and Analysing Data, Open University Press, Buckingham, 2000

Heal, M. & Wigram, T. (ed.), Music Therapy in Health and Education, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1993

Jaquiss, V. & Paterson. D., Meeting SEN in the Curriculum: Music, David Fulton Publishers, London, 2005

Kumin, L., Early Communication Skills for Children with Down Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals, Woodbine House, Bethesda, 2003 (2nd ed.)

Lapage, C. P., Feeblemindedness in Children of School Age, The University Press, Manchester, 1911

Liddell, C., So You Want to Play By Ear? A Practical Guide to Improvisation, Stainer and Bell, London, 1980

Lorenz, S., Children with Down's Syndrome: A Guide for Teachers and Learning Support Assistants in Mainstream Primary and Secondary Schools, David Fulton Publishers, London, 1998

Mardell, D., Danny's Challenge: The True Story of a Father Learning to Love His Son, Short Books, London, 2005

Newton, Dr. R., The Down's Syndrome Handbook: A Practical Guide for Parents and Carers, Vermilion, London, 2004, New/Revised Edition

Niedecken, D., Nameless: Understanding Learning Disability, Brunner-Routledge, East Sussex, 2003

Nordoff, P. & Robbins, C., Creative Music Therapy – Individualized Treatment for the Handicapped Child, The John Day Company, New York, 1977

Nordoff, P. & Robbins, C., Music Therapy in Special Education, MacDonald and Evans Limited, London, 1975

Nordoff, P. & Robbins, C., Therapy in Music for Handicapped Children, Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1973

Ockleford, A., Music for Children and Young People with Complex Needs, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008

Paterson, A. & Zimmermann, S. (eds.), No Need For Words – Special Needs in Music Education, National Association of Music Educators, Matlock, 2006

Pavlicevic, M. (ed.), Music Therapy in Children's Hospices – Jessie's Fund in Action, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 2005

Philip, L, H., Piano Technique – Tone, Touch, Phrasing and Dynamics, Dover Publications, New York, 1982

Priestley, M. Essays on Analytical Music Therapy, Barcelona Publishers, Pennsylvania, 1994

Schalkwijk, F. W., Music and People with Developmental Disabilities: Music Therapy, Remedial Music Making and Musical Activities, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1994

Searle, A., Introducing Research and Data in Psychology – A Guide to Methods and Analysis, Routledge, London, 1999

Selikowitz, M., Down Syndrome: The Facts, Oxford University Press, New York, 1997, 2nd ed.

Sharp, J. A., Peters, J. & Howard, K., The Management of a Student Research Project, Gower Publishing Limited, Aldershot, 2002

Sherlock, E. B., The Feeble Minded, Macmillan, London, 1911

Shuttleworth, G. E., Mentally Deficient Children, London, 1900 (2nd ed.)

Sinason, V., Mental Handicap and the Human Condition: New Approaches from the Tavistock, Free Association Books Ltd, London, 1992

Sloboda, J., The Musical Mind: The Cognitive Psychology of Music, Oxford Science Publications, New York, 1985

Streeter, E., Making Music with the Young Child with Special Needs: A Guide for Parents, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1993

Stringer, M. (Foreword), The Music Teacher's Handbook – The Complete Resource for All Instrumental and Singing Teachers, Faber Music, London, 2005

Warren, B., Richard, R. J. & Brimbal, J., Drama and the Arts for Adults with Down's Syndrome – Benefits, Options and Resources, The Down Syndrome Educational Trust, Portsmouth, 2005

Wigram, T., Pedersen, I. N. & Bonde, L. O., A Comprehensive Guide to Music Therapy, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 2002

Wigram, T., Saperston, B. & West, R. (ed.), The Art and Science of Music Therapy: A Handbook, Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, 1995

Barker, J. “Singing and Music as Aids to Language Development, and it's Relevance with Down Syndrome”, Down's Syndrome News and Update (1999), 1(3), 133-135

Blacketer-Simmonds, D. A., “An Investigation into the Supposed Differences Existing Between Mongols and Other Mentally Defective Subjects with Regards to Certain Psychological Traits”, Journal of Mental Science (1953), 99, 702-719

Bower, A. & Hayes, A., “Short-term Memory Deficits and Down's Syndrome: A Comparative Study”, Down Syndrome Research and Practice (1994), 2(2), 47-50

Brushfield, T., “Mongolism”, British Journal of Childhood Diseases (1924), 21, 240-258

Cantor, G. N. & Girardeau, F. L., “Rhythmic Discrimination Ability in Mongoloid and Normal Children”, American Journal of Mental Deficiency (1959), 63(4), 621-625

Chesney, J., “Keeping in Tune with the Patient: Choosing Music for Therapy”, British Journal of Music Therapy (1980), 11(2), 8-15

Cotter, V. W., & J. E. Spradlin, “A Non-Verbal Technique for Measuring Music Preference”, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology (1971), 11(3), 357-365

Edenfield, T. N. & Jane E. Hughes, J. E., “The Relationship of a Choral Music Curriculum to the Development of Singing Ability in Secondary Students with Down Syndrome”, Music Therapy Perspectives (1991), 9, 82-86

Feeley, K. & Jones, E., “Teaching Spontaneous Responses to a Young Child with Down Syndrome”, Down Syndrome Research and Practice (2008), 12(2), 148-152

Flowers, E., “Musical Sound Perception in Normal Children and Children with Down's Syndrome”, Journal of Music Therapy (1984), 21(3), 146-154

Fraser, J. & Mitchell, A., “Kalmuc Idiocy”, Journal of Mental Science, 1876

Heal, M. & O'Hara, J., “The Music Therapy of an Anorectic Mentally Handicapped Adult”, British Journal of Medical Psychology (1993), 66, 33-41

Heal, M. “The Use of Pre-composed Songs with a Highly Defended Client”, British Journal of Music Therapy (1989), 3, 10-15

Moorcroft-Cuckle, P., “Short Reports – Type of School Attended by Children with Down's Syndrome”, Educational Research (1993), 35(3), 267-269

Orne, M. T., “On the Social Psychology of the Psychological Experiment”, American Psychologist (1962), 17(11), 776-783

Rollin, H. R., “Personality in Mongolism with Special Reference to the Incidence of Catatonic Psychosis”, American Journal of Mental Deficiency (1946), 51, 219-237

Silva, D, A., Friedlander, B, Z. & Knight, M. S., “Multihandicapped Children's Preferences for Pure Tones and Speech Stimuli as a Method of Assessing Auditory Capabilities”, American Journal of Mental Deficiency (1978), 83(1), 29-36

Sinason, V., “Secondary Mental Handicap and its Relationship to Trauma”, Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy (1986), 2(2), 131-154

Stratford, B. & Ching, E. Y., “Rhythm and Time in the Perception of Down's Syndrome Children”, Journal of Medical Deficiency Research (1983), 27(1), 23-38

Wishart, J., “Learning the Hard Way: Avoidance Strategies in Young Children with Down's Syndrome”, Down Syndrome Research and Practice (1993), 1(2), 47-55

Wylie, J., “The Holistic Learning Outcomes of Musical Play for Children with Down Syndrome”, Down Syndrome News and Update (2006), 5(2), 54-58

Hopson, G. R., “Approaches to Instrumental and Vocal Tuition for Children with a Learning Disability – An Investigation into the Adaption of Conventional Teaching Techniques”, Unpublished work, RNCM Manchester, 2004

Author unknown, “British Suzuki Institute” in British Suzuki Institute, Date unknown, accessed on 01/03/2009, <http://www.britishsuzuki.org.uk/>

Author unknown, “History” in British Suzuki Institute, Date unknown, accessed on 01/03/2009, <http://www.britishsuzuki.org.uk/rpmServer/generatorSystem/asp/rpmServer_GoGenerate.asp?intSiteID=15&intPageID=3&intNavbarOpen_Level1_ID=1>

Author unknown, “Philosophy” in British Suzuki Institute, Date unknown, accessed on 01/03/2009, <http://www.britishsuzuki.org.uk/rpmServer/generatorSystem/asp/rpmServer_GoGenerate.asp?intSiteID=15&intPageID=4&intNavbarOpen_Level1_ID=2>

Author unknown, “Charlotte Horner - Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in YouTube, Date unknown, accessed on 25/02/2009, <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJRekJ4bmDM&eurl=http://colourmuse.com/in_action_disability.php>

Author unknown, “Dyslexia, Dyscalculia and Maths” in The British Dyslexia Association, 27 September 2007, accessed on 27/02/2009, <http://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/about-dyslexia/schools-colleges-and-universities/dyscalculia.html>

Author unknown, “Performance Assessment” in Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, Date unknown, accessed on 25/02/2009, <http://www.abrsm.org/?page=exams/performanceAssessment>

Cross, R. “Instrumental Teaching for People with a Learning Disability” in Melody, 2008, accessed on 14/11/2008, <http://www.melody.me.uk/>

Cross. R., “Alternative Notation” in Melody, 2008, accessed on 25/02/2009, <http://www.melody.me.uk/teacher-resources/alt-notation.htm>

Cross, R., “Teacher Resources” in Melody, 2008, accessed on 25/02/2009, <http://www.melody.me.uk/teacher-resources.htm>

Gowers, C., “Working with Children with Special Needs: Girl With Down's Syndrome” in Piano Professional, January 2007, accessed on 14/11/2008, <http://www.europeansuzuki.org/web_journal/arts07/Special_needs.pdf>

Horner, V., “Useful Resources” in Maths Extra, 2007, accessed on 14/11/2008, <http://www.mathsextra.com/links.htm>

McGuire, D., “If People with Down's Syndrome Ruled the World” in National Association for Down's Syndrome, 2005, accessed on 14/11/2008, <http://www.nads.org/pages_new/news/ruletheworld.html>

Steer, M. M. “Colour Muse by Maxwell Steer” in Melody, March 2006, accessed on 26/02/2009, <http://www.melody.me.uk/teacher-resources/first-steps-in-learning/38.htm>