|

|

The Riverbend Down Syndrome Association is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and can receive tax deductible contributions. Our Employer Identification Number is: 14-1982424.

This issue is dedicated to the memory of Dick Brown (Oct. 8, 1939 - Jun. 16, 2009) of Grafton, IL, father of 13-year-old Karrie, Dick Brown had been in hospice for heart and renal failure when Karrie won the chance to go to the state Special Olympics, and her mother Sue said they were "doing this for Dad." Sue said they called the hospice from the Special Olympics on Saturday, and the workers told her Dick – who was no longer capable of speaking – smiled at the news. See Belleville News-Democrat article in this issue.

Local Events

October 9, 2009 — 7:00 p.m. ~ 10:00 p.m. Harvest Moon. Wine & Cheese Tasting. The Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis and The Wine & Cheese Place invite you for an evening of fun and food featuring a variety of domestic and imported wines and assorted cheeses. 7435 Forsyth Boulevard. St. Louis, MO 63105. $40 per guest. Reservations: (314) 961-2504 or visit http://www.dsagsl.org.

October 17, 2009 — Reception: 10:00 a.m., Fashion Show - 11:00 a.m., Lunch: 12:00 p.m. The Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis 1st Annual Catch a Shooting Star Luncheon & Fashion Show. Marriott West. Showcasing the beauty and abilities of individuals with Down syndrome. Fashion and accessories by Target. MC: Cindy Preszler. Tickets: Adult $35, Child $25. For more For information contact Kathy Crump (636) 394-4967, E-mail: kcrump44@hotmail.com or Betty Guarraia (314) 275-7871, E-mail: lguar@aol.com.

October 26 — Transitioning Children from Early Intervention to Early Childhood Special Education Services. Registration & Continental Breakfast: 8:30 a.m. Workshop: 9:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. The Keller Convention Center at the Hilton Garden Inn. 1202 North Keller Drive. Effingham, Illinois 62401. (217) 347-5115. Intended Audience: Early Intervention Providers and family members of children birth to age 3 who are receiving services through Child and Family Connections (Early Intervention).

|

|

This training will assist EI and school district personnel in meeting the obligations of IDEA through providing a smooth and effective transition for children and their families, from EI to school district services. For registration information contact STARnet Region IV: http://roe.stclair.k12.il.us/starnet or (618) 825-3966.

Down Syndrome Articles

'Look at her now': Collinsville girl brings home Special Olympics gold, silver for ailing father by Elizabeth Donald, E-mail: edonald@bnd.com. Jun. 16, 2009. © 2009 Belleville News-Democrat. All Rights Reserved. URL: http://www.bnd.com/

Karrie Brown high-fived the kids of the YMCA day camp, her face shining with delight as they applauded her — and her gold and silver medals.

Karrie, 13, just competed in her first Special Olympics. She had won the gold medal at the regional competition for the 50-meter dash and softball throw, and she was the sole student from Collinsville Unit 10 schools to attend the state competition this weekend.

She brought home two medals. And she did it, in part, for her father.

It's a tough time for Karrie. Her father, Richard Brown, is currently in hospice. Her mother, Sue Brown, said they weren't sure Richard would make it through the weekend while Karrie competed.

"But he wanted her to go; we're doing this for Dad," Sue Brown said.

Karrie has Down syndrome and mild autism. Before she started the inclusive programs at the Collinsville-Maryville-Troy YMCA, Sue said she would have difficulty even entering a gymnasium full of loud, clapping children due to the sensory overload.

"Look at her now," Sue said, watching her daughter raise her thumbs high in joy as her camp friends cheered her.

|

|

|

At first, Sue said, she didn't really "buy into" the Special Olympics because she believes in the inclusive programs that put special-needs children with typically developing children. Those programs have helped Karrie develop friendships and break down the stigmas surrounding children with mental and physical disabilities, she said. She wanted Karrie in the "real world" because it is the world in which she will have to function, she said.

"I took her to the district games because she wanted to go, but when I saw the look on her face when they put the medal around her neck, I started to cry," she said. "She sometimes realizes (at school) that other kids let her win, but she won these fair and square. Her self-esteem has just blossomed with it."

So Sue took Karrie to the state games and tried to prepare herself and Karrie for a participant's ribbon. Karrie was up against older kids, and it's been rough to prepare while dealing with Karrie's father's illness.

But Karrie blew them all away.

"I was fast," Karrie said, holding up her gold medal for the 50-meter dash with a smile. She also threw the ball pretty hard, she said, with her silver medal for the softball throw.

So when Karrie returned to day camp Monday, the campers gathered to cheer her and present a "Congratulations Karrie" sign they had made, along with a framed certificate from YMCA of Southwest Illinois. This seemed to make Karrie almost as happy as the medals, carrying it throughout the gym to show her fellow campers.

And when Sue Brown called the hospice from the games in Bloomington, the attendants told her Richard Brown, who isn't capable of speech at this point, smiled at the news of his daughter's accomplishment.

Sue began to sniffle again as she watched Karrie's obvious joy at the YMCA ceremony.

"When Karrie was born, they told me never to expect anything of her, and she has brought me more joy than I ever imagined," Sue said. "There's nothing artificial about her joy, it just bubbles over."

A Pharmacotherapy for Down Syndrome? By Alberto Costa, M.D., Ph.D. Mile High Down Syndrome Association's Down's Update, Oct/Nov 2008. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

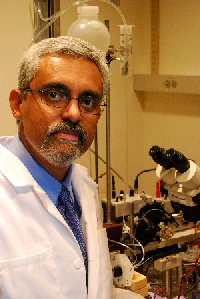

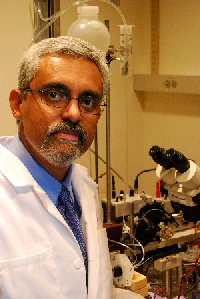

Because many readers of Down's Update are parents of very young children who may have not heard of me or my research, perhaps a reintroduction is in order. My name is Alberto Costa, and I wear many hats. I am a medical doctor and a brain scientist who has dedicated the last 12 years exclusively to the study of Down syndrome. I am an Associate Professor of Medicine and Neuroscience at the University of Colorado Denver. And I am also the proud parent of a child with Down syndrome named Tyche.

|

| Alberto Costa, M.D., Ph.D. |

Thirteen years ago, Tyche was born in Houston, Texas with an abnormal narrowing of the first portion of her small intestine, known as duodenal stenosis, which needed to be corrected surgically just as we celebrated her first month of life. This was to be the first of many trips to the hospital that my wife and I had to take over the subsequent couple of years. Nowadays, Tyche is generally healthy. But this state of affairs sometimes disguises an underlying severe food allergy, which in Tyche's case can lead to anaphylaxis if she drinks as little as half an ounce of milk or eat a bite from a boiled egg. Tyche attends middle school in a mostly inclusive setting. Even though she struggles with most of the seventh-grade material, she has an uncanny spelling ability (even when compared to her typical peers) and is starting to show progressively improved grasp of math and grammar concepts (which, overall, are at the fifth grade level).

Since just a few months after Tyche's birth, I have become driven by an "informed hope" that the cognitive deficits associated with her genetic disorder could be ameliorated by one or more medications known to affect the function of the brain. This was the beginning of a twelve-year professional and personal journey in search for a pharmacotherapy designed to improve the quality of life of persons with Down syndrome.

At the time my daughter was born, I was finishing my postgraduate research training at Baylor College of Medicine. Even though I could trace my passion for scientific matters from when I was eight years old, I have to confess that, in those days, I was becoming progressively more jaded with the praxis of science. As an example of my own personal experience on the transformative effects that the birth of a child with Down syndrome can have on one's life, I can attest that Tyche's birth rekindled and refocused my passion for the scientific enterprise. We uprooted from Texas and went to Maine where I joined the faculty of The Jackson Laboratory, an amazing scientific facility dedicated to creating and studying mouse models of human diseases and disorders. Just a few years before we moved, a Senior Staff Scientist of that institution, Dr. Muriel Davisson, had created the Ts65Dn mouse, the first mouse model for Down syndrome that had an extra chromosome and that lived to adulthood.

The Ts65Dn mouse has taught us a lot about the biology of Down syndrome. These mice display many features that resemble those seen in persons with Down syndrome. But, perhaps more importantly, these animals have hinted to the fact that Down syndrome is associated with severe dysfunction of the brain structure called the hippocampus. The hippocampus is thought to be important for the formation or retention of new memories, and is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage in Alzheimer's disease. Work done at the University of Denver by Drs. Bruce Pennington, Jennifer Moon, and Lynn Nadel, indeed confirmed that the function of the hippocampus is disproportionally affected in persons with Down syndrome.

I have been doing research with Ts65Dn mice and other mouse models of Down syndrome for over twelve years now. My background as a physician-scientist has, additionally, allowed me to conduct various neurophysiological assessments in individuals with Down syndrome in the greater Denver area. I also have been privileged to observe the general evolution of the Down syndrome research field from the inside by participating in collaborative program projects at The Jackson Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, and the Eleanor Roosevelt Institute. During this time, it became clear to me that genetics would only go so far towards addressing treatment options for the cognitive impairments associated with Down syndrome. As a result, my lab has invested most of its energies in testing potential therapies that might address such cognitive deficits in mouse models. In fact, I am the first person awarded with a major grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study exclusively potential pharmacotherapies for Down syndrome. During the five years covered by that research grant and the three subsequent years, I have tested a dozen different brain-acting compounds on Ts65Dn mice. Recently, our research has pinpointed the unique efficacy of a drug called memantine hydrochloride (memantine) in ameliorating learning and memory deficits of the Ts65Dn mouse (recently published in the journal Neuropsycopharmacology). Memantine is a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer-type dementia. Recent clinical studies suggest that memantine also may be clinically useful and well tolerated in young individuals with other conditions that produce cognitive disabilities, such as autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

In order to build off of our exciting preclinical findings, I have put together a pilot clinical trial to study the tolerability and efficacy of memantine in young adults with Down syndrome. I am fortunate to lead an impressive group of physicians and psychologists in this endeavor. Dr. Pennington has been instrumental in helping with the design of the trial, and his former graduate student, Dr. Richard Boada, will be the neuropsychologist responsible for applying the psychological tests associated with the trial. Our research protocol has been funded as an investigator-initiated grant by Forest Pharmaceuticals and has received institutional review board approval from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB). We have started recruitment for this study very recently, and the clinical trial is taking place at the University of Colorado and The Children's Hospital at the Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

The purpose of our pilot clinical trial is to determine whether memantine has the potential to help improve memory and other cognitive abilities of young adults with Down syndrome over the course of a 16-week treatment. Forty persons with Down syndrome of both genders, aged 18-32 years, will take part in this study. This is a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study, which means that each participant will have a 50/50 chance of being assigned to receive either the memantine pills or placebo (inactive pills). Also, neither the study participants nor the research personnel will know who is receiving active medication or placebo until the end of the study. Based on memantine's mode of action and current knowledge on brain function in persons with Down syndrome, our hypothesis is that memantine may improve test scores of young adults with Down syndrome on memory tests targeted at the function of the brain structure called the hippocampus. This research project was also designed to explore whether memantine is well tolerated by the study participants.

There is also a small but realistic possibility that memantine may indeed delay the onset of Alzheimer-type disease in young adults with Down syndrome. But our present study was not designed to test this hypothesis. Depending on the results of our study, we hope to expand the size and scope of our investigations and pursue a longer, multicenter trial on memantine in persons with Down syndrome. We also plan a study involving younger participants for the future.

If you want to learn more or participate in this clinical trial, you can contact me at Alberto.Costa@uchsc.edu. Also, I am scheduled to speak at an MHDSA-sponsored research update seminar to talk more about this and other projects on Thursday, November 20th, from 6:00-8:00 PM at the Jeffco Developmental Disabilities Resource Center near Green Mountain. The address is 11177 West 8th Avenue, Lakewood, 80215.

It is important to notice that my research would not have been possible without funding at various stages from the National Down Syndrome Society, the Enoch-Gelbard Foundation, the National Institute for Child Health and Development, the Anna & John Sie Foundation, the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities, the Jerome Lejeune Foundation, the Lowe Fund of the Denver Foundation, the Lutheran Good Samaritan, Colorado Springs Down Syndrome Association, and Mile High Down Syndrome Association. Even though this may be an impressive list, this does not erase the fact that, as I have mentioned many times (check, for example, http://www.mhdsa.org/ResearchCosta.htm), funding for Down syndrome research is still very small compared to funding for other disorders associated with intellectual disabilities, such as Autism and Fragile X. If you wish to help, please send a donation or volunteer your time to the Down Syndrome Research Fund Raising Group (DSR|FRG) c/o Mile High Down Syndrome Association, 2121 S. Oneida St, Suite 600, Denver, CO 80224.

Counting a little blessing by Beverly Beckham. E-mail: bevbeckham@aol.com. The Boston Globe. June 14, 2009. Reprinted with the permission of the author. © Copyright 2009 Globe Newspaper Company.

Blessed is a word I find myself saying a lot lately. How blessed I am. How blessed my family is. How blessed we are to have Lucy.

Six years ago, I didn't feel blessed. Lucy, my first grandchild, my daughter's child, was 12 hours old when we learned she had Down syndrome. We wept. Three days later, we were told she had holes in her heart and would need surgery. We took her home and fed her and held her and rocked her and sang to her. And we prayed.

Fear consumed us then. We worried about her health. Were her lips blue? Was she sweating from exertion or was the room too warm? We worried about her future. Would she walk? Would she talk? We worried about our future. Would the stress of all this worry pull our family apart?

Heart surgery. And we almost lost her. Then more heart surgery and, again, a crisis. Blessed? The word never crossed my mind.

Then slowly things got better.

If only life were like a book and you could peek ahead. Lucy will be 6 on Saturday. If only, when she was new and we were scared, we could have had a glimpse of Lucy now.

When she was little, 2, 3, maybe even 4, she used to practice talking in her crib. Away from everyone, she would chatter, naming things, her stuffed animals, the toys in her room, the people in her books and in her life. Over and over, she'd say Mommy, Daddy, Adam, Mimi, cow, duck, cat, and every other word she knew.

She was quieter in front of people, shy until she got a word right.

It took time, but she got them right. This is Lucy. Give her time and she'll amaze you.

These are things about her now that I never could have imagined then: that her favorite movie would be "Gone With the Wind." That she would know all the characters, except for Sue Ellen. ("Who's that?" she asks every time Scarlet's sister comes on the screen. Poor Sue Ellen - forgettable even to a child.)

That she would always race to the door to greet her mom and dad, dropping whatever it is she is doing to hug them, to tell them with her smile and her open arms - even if they've been gone just 10 minutes - how glad she is to see them.

That she would love the "peace be with you" moment in church. That she would say "peace," reach for hand after hand, look into a stranger's eyes and smile. And that even the most reluctant hand-shaker would smile back.

And that she would love our neighbor Al, and seek him out in his yard, in his house, in my house. "Al! Al!" Katherine, his wife, the one who makes her favorite cookies, but Al the one who has her heart.

It's not all roses of course, with Lucy. She doesn't understand that the street is dangerous and that you can't sit down when you're an outfielder and that the DVD player sometimes sticks and whining doesn't unstick it.

In these ways she is a lot like a typical 6-year-old.

But she is not typical.

It takes her longer to learn and longer to understand. But when she does? It's like the circus has come to town. She says a whole sentence "I want to have a banana, please." She puts together a puzzle. She matches colors and shapes. She climbs to the top of the slide, sits, and glides down. She stands at the window and reenacts a scene from "The Little Princess." The Wallendas doing headstands on a tightrope couldn't thrill us more.

Sometimes when I watch children her age do things effortlessly, my heart aches a little. But then Lucy will saunter by, climb on my lap, or say hi and keep on walking, and I will be bowled over by her presence, by the amazing gift of her.

How blessed I am. How lucky to be loving her. And how easy she is to love.

St. Louis Cardinals fan feels uplifted after fall by Todd C. Frankel. Sunday, Sep. 4, 2009. E-mail: TFrankel@post-dispatch.com, (314) 340-8110. Reprint permission granted by Mark Learman, E-mail: MLearman@post-dispatch.com. © 2009 St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

He lay on his back in the dirt of the Pittsburgh ballpark. His neck hurt. Striking his face on the crushed rock along the first-base side felt like breaking through glass. He was bloodied. And the foul ball was gone. He had missed it, missed his one chance to grab a game ball for his son on the boy's 21st birthday.

|

| AUG. 7, 2009 – Tim Tepas and his son, Keith, attend a Pittsburgh-Cardinals game for Keith's 21st birthday. |

Tim Tepas, a retired schoolteacher, wanted only to climb over the short railing and sit back down next to his son. Disappear. Forget the whole thing. But the television cameras were on him. The stadium seemed to gasp in unison at his fall along the sidelines of that Pirates-Cardinals game in early August.

Please lie down, sir. Don't try to get up, sir.

The hands, huge meaty mitts, eased him to the ground, held him still.

Don't try to get up, sir.

Tepas was struck by the voice, its confidence, its calm, the way he was called "sir" again and again.

He looked up at the sky and struggled to focus on the face above him. He studied the man's ballcap. He could make out the number 5 written under the bill.

Albert Pujols. The father just knew. This is Albert Pujols.

Two strangers, one a fan and the other a superstar athlete, both fathers of children with Down syndrome.

Some say it was coincidence. Others call it fate.

Whatever caused that accidental meeting there along the edges of the ballgame that night outlived anything that happened on the field. During the entire 8½- minute ordeal on the field, Pujols stayed with Tepas. TV and radio announcers were mystified. Fans talked of witnessing a moment of pure concern.

But to truly understand what occurred — to understand what, in some small way, drove Tepas to reach for that foul ball — you have to know about Tepas and his son Keith.

And you have to know about the letter, the one Tepas wrote to Pujols long before the game, but never sent. A letter about doubt and acceptance and the parable of the bumblebee.

When Tepas fell, the letter sat forgotten in a white tote bag under his seat just a few feet away.

Father and son had driven down from Buffalo, N.Y., in Tepas' Hyundai. They loaded up on Gatorade and music for the 3½-hour trip on Friday, Aug. 7.

They both wore Cardinals T-shirts. Keith wore a red Cardinals cap. He plays on the Cardinals in a softball league for disabled adults. He sleeps on Cardinals bedsheets at home.

The father liked Pujols — more as a person than a player. Tepas recalled reading about Pujols and his 11-year-old daughter, Isabella, who has Down syndrome. She was 3 months old when Pujols met her mom, his future wife. Pujols became an advocate for Down syndrome children with his charitable foundation.

For Keith's birthday, Tepas at first planned to take his son to a minor league game in Buffalo. They have season tickets. Keith can name players who years ago played there. In Pittsburgh, he would point to right field and note that the Cardinals' Ryan Ludwick used to play for the Bisons.

But the Bisons were out of town. So Tepas, an impulsive and gregarious 63-year-old with gray hair and a mustache, aimed for something grander.

Tepas splurged on tickets for the Pirates game — $224 for the pair. Section 7, right along the field.

He figured it was an important milestone for Keith. It was an important milestone for Tepas, too. He had spent years battling his own doubts, worrying about his son, wondering what would become of him as he grew older.

The doctors warned Tepas and his wife there would be delays with Down syndrome, a genetic condition that causes developmental disabilities and distinctive physical features. Keith would lag behind children his age. It wore on the father. Watching other kids walk. Other kids talk. Wondering when it would be Keith's turn.

"During the first three years, you're like, what's wrong with this kid? When is he going to blossom?" Tepas says.

He adds: "It's been challenging, I'll be honest with you. I heard that when you have a special needs child, as many as 90 percent of those parents end up divorced."

Tepas was divorced after one year. His former wife got custody of Keith. But Tepas stayed in the boy's life. Saw him four days a week, sometimes more.

Attended his therapy sessions, his sporting events, his Boy Scout meetings.

Tepas remembers when he began to see his son in a new way. Keith was 7. Father and son were running side by side in a county park. They tossed a blue-and-yellow foam football back and forth. It felt so ordinary, so simple, this staple of fathers and sons.

The father told himself: OK, Tim, you can stop worrying.

"I consider him a real blessing in my life," Tepas says now.

He can rattle off his son's achievements, apologizing as he goes for sounding boastful. Two years ago, Keith became an Eagle Scout. He graduated high school this summer, his father buying him a custom-fit suit for the occasion. He's good at spelling. And miniature golf. He does not talk much, preferring to telegraph his speech through simple words or gestures. But his father can glean more than enough from one of his son's gleeful thumbs-ups.

"It's kind of neat in a way, because of his innocence, I don't think he's ever going to change much," Tepas says. "He'll still hug me when he's 30 or 40 or 50. He's uninhibited that way."

The relationship between father and son developed its own routines. Keith loves routine. In recent years, one routine has centered on playing baseball, starting in the spring and lasting until it gets too cold.

Three days a week, Tepas picks up Keith and they head to a little league field. Tepas pitches from a box of old balls. Keith wields the bat. The father keeps stats, tracking the progress of his son like he is a major league prospect. The father notes with precision how many balls Keith hits over the fence, how far they travel. He walks off the distances to be sure.

With the number of home runs, the father can see his son's growth. Keith is not tall, standing just under 5 feet 2. But he has a slugger's swing. Two home runs the first year, eight the next, then 26, 53, 97 and 94 so far into their private season.

And every visit to the ballpark ends the same way. A private celebration modeled on the Friday night fireworks at Bisons games. They huddle together and rest one hand on top of the other in the middle. They shout "1,2,3, fireworks!" Their hands shoot skyward in imitation of the pyrotechnics.

Only then is the game truly over.

In Pittsburgh, during the middle of the seventh inning, with the game tied 4-4, Tepas considered leaving. They faced a long drive home. Tepas reminded himself to remove the homemade orange-and-white "Happy 21st Keith" sign taped atop the railing.

But they stuck around.

The Pirates were at bat. Chris Carpenter was on the mound. One out. Two runners on base. Garrett Jones, a lefty, at the plate. Carpenter's first pitch was outside. His next pitch was low. But Jones reached for it, striking the ball straight-armed, like he was hitting a sand wedge. The ball spun into foul territory toward the stands.

This is going to be easy, Tepas thought.

The bouncing ball appeared to be headed straight for him. He stood up, reached out with his left hand. He planted his right hand on the railing. But his view changed as he stood. The ball appeared farther off to his left. Difficult to backhand. He extended his right hand. He flipped over the railing. His body launched downward, his arms offering no protection, his legs thrown high above. His face slammed to the ground.

|

| AUG. 7, 2009 – Pittsburgh Pirates first base coach Perry Hill (8) and Cardinals first baseman Albert Pujols (left) come to the aid of a fan who tried to retrieve a foul ball during the seventh inning of a game in Pittsburgh. (AP) |

The ball caromed off the railing and scooted into right field.

"Man down," said a Pittsburgh TV announcer.

"Wow," added the play-by-play man.

"Wow. Oh my goodness."

Pujols, playing first base about 40 feet away, reached Tepas first. He knelt beside him. He urged him to lie down.

Pirates first base coach Perry Hill arrived next. He grabbed Tepas' feet. Hill had never seen a fan suffer a fall like that. Stadium staff ran over. Trainers from both teams and paramedics crowded around Tepas. Pujols still knelt by his head.

Hill glanced over his shoulder at Tepas' son. He had noticed the pair earlier in the game. Now he picked up Pujols' mitt and walked over to Keith, still in the stands. He asked Keith whether he would like to touch Pujols' glove. They talked about the handmade "Happy 21st Keith" sign. Hill tried to position himself to block the son's view. Hill looked back at the field, saw Pujols still there.

"The way he landed so awkwardly on his neck," said Cardinals TV play-by-play man Dan McLaughlin, reacting to a replay. "His neck was bent. It's not so much the cut on the forehead that you saw, but I'm sure they're very concerned about his neck area and his back."

Lying on the ground, Tepas was annoyed to hear Pujols tell the trainers he did not like the way he landed on his neck. Tepas felt fine. Woozy, battered, but fine. Yet he was not going to fight them. They asked him to wiggle his fingers and his toes. He did. They asked about tingling, about radiating pain. He felt none.

Minutes ticked by as they strapped Tepas to a board and secured his neck with foam blocks. And still Pujols was there, in the thick of it.

"I'm almost wondering if this is a friend of Albert's," said Al Hrabrosky on the Cardinals TV broadcast.

Mike Shannon, doing the Cardinals radio show, sounded incredulous.

"Look at Albert, he's right in there! He's going to help lift the stretcher.

Better get Albert out of there," Shannon said, laughing. "Move him out of there! We know he has a lot of compassion, but we don't need him hurting his back lifting him up."

Pujols let the paramedics wheel Tepas out on a stretcher through the right field fence. Pujols stood, hitched up his pants and walked over to Keith, who now sat on a small ballpark utility vehicle, about to follow his father. Keith sat facing away from the medical drama. He tugged on the bill of his red Cardinals cap as he scanned the diamond. Pujols leaned over and tapped Keith on the shoulder, spoke to him. Pujols smiled. Made sure Keith had gotten the foul ball his father wanted for him.

Tepas was released from the hospital after midnight. As he left, the hospital staff teased Tepas that he was famous, his fall already appearing on ESPN and YouTube. His neck was sore. His face was bruised. But he had no serious injuries. Tepas wanted only to get home, where in a few days a Pujols autographed baseball would arrive for Keith. They drove through the night. The father asked his son whether he had been scared by what happened on the field. The son said simply, "No."

And in the back of the car sat the tote bag with the letter.

Tepas was not sure why he had written it. Pujols did not need to hear from him.

But Tepas needed to share his son's story, wanted another father to know what he knows, what he took so long to learn. About his son. About the bumblebee, too.

The letter, after a short introduction, starts with a note: "According to the laws of aerodynamics, the bumblebee can't fly. But the bumblebee doesn't know that. So it flies." The letter details in numbers and statistics Keith's hitting prowess and his off-the-field achievements.

And it ends like this: "He is a blessing in my life and I thank the Lord for putting him in my life. Like the bumblebee, he doesn't know that he's not supposed to fly."

This weekend, Tepas and Keith are driving back to Pittsburgh for a series with the Cardinals, attending at the Pirates' invitation.

No need to bring the letter. Tepas finally mailed it last week.

And he plans to let others chase the foul balls.

Web Wanderings

New law helps Illinois kids get therapies. Triage. Making Sense of Health Car by Judith Graham. Chicago Tribune blog. April 14, 2009. URL: http://newsblogs.chicagotribune.com/triage/2009/04/new-law-helps-illinois-kids-get-therapies.html#

Illinois will extend assistance to parents of children with Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, autism and other developmental disorders under a new law (Senate Bill 101) signed by Gov. Patrick Quinn last week.

For the first time, the law will require insurance companies to pay for these youngsters' speech, physical and occupational therapies. Specifically, it says insurers must treat so-called "habilitative" therapies for youngsters with developmental disabilities in the same way they treat "rehabilitative" therapies.

The measure, strongly supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics, goes into effect Jan. 1, 2010.

Habilitative therapies are designed to teach a person new skills and maximize functioning; rehabilitative therapies are designed to help someone recover skills that have been lost.

Think of a 5-year-old with cerebral palsy who needs help learning how to walk and talk. Insurers routinely deny reimbursement for physical and speech "habilitative" therapy on the grounds that these are educational, not medical, services, said Dr. Alan Rosenblatt, a Chicago pediatrician.

If, however, a child walked and talked and then became unable to do so because of an accident, the same insurer routinely covers "rehabilitative" therapies to help restore those skills, deeming those medical necessary services.

The new law won't allow those kinds of distinctions for children with developmental disabilities up to the age of 19. As a result, more children should start receiving habilitative therapies and families that have paid out of pocket for the services will get financial relief.

Father's Journal

Anatomy

At the Museé Rodin in Paris I made sure Emmanuel did not inadvertently take a photograph of some voluptuous bust that would not meet with mother's approval. Thank God for digital cameras.

|

|

"Research shows early intervention can make a significant impact on the quality of life and long-term potential for children" with developmental disabilities, Rosenblatt said. "This will ensure that Illinois children with disabilities get necessary treatments to help them reach their full potential."

It's important to note that the law doesn't require insurers to offer a minimum level of coverage for either habilitative or rehabilitative therapies. Many insurers impose restrictions on any kind of therapy, and those will still apply.

Illinois becomes the third area to enact this kind of legislation, after Maryland and the District of Columbia.