|

The Third Annual Picnic was held on June 12th and new area families were in attendance.

The focus of this issue is inclusion, with two articles: "Does Inclusion Work?" by Caroline Grimaldi and a Belleville News-Democrat article on Charlotte Goodman's graduation.

STARnet Illinois Region IV Workshops

July 16. 9:00 - 3:00 p.m. Multi-Sensory Activities for Pre-School Children. This workshop presents the collaborative experience and work of a pre-school teacher and a physical therapist in the development of multi-sensory activities for inclusive pre-school classrooms. Presenters: Sandy Cronwell, M. Ed. in Special Education and Georgia Phillips, MS in Education (Special Pediatric PT). Location: Holiday Inn, Collinsville. For information, contact STARnet at 397-8930.

July 27. 9:00 - 3:30 p.m. Why Music & Movement for Young Children? This workshop is for educators, caregivers, and parents and is highly interactive and will begin with an introduction to music and movement and proceed to an understanding of locomotor and non-locomotor movements. Presenter: Linda Richards. Location: Ramada/Keller Convention Center, Effingham. For information, contact STARnet at 397-8930.

|

|

August 4. 9:00 - 3:00 p.m. Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) Training. PECS is a functional communication system for use with pre-schoolers and others who lack a consistent pattern of communication that can be easily understood. Participation by teams is encouraged and parents are welcomed. Presenters: Diane, Special Services coordinator for the Belleville Area Special Services Cooperative (BASSC) and Cheryl Newsome, speech language pathologist who conducts augmentative communication assessments and training for BASSC. Location: Holiday Inn, Mt. Vernon. For information, contact STARnet at 397-8930.

Regional Events

5th Annual Heartland Disability Rights March & Rally Weekend. St. Louis, MO. July 24-25 at the St. Louis Community College at Forest Park. This event will celebrate the 9th anniversary of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The March & Rally is a great opportunity to advocate, as well as learn about issues which are of concern to people with disabilities from nationally known disability rights speakers. For more information call (314) 567-1558, TTY: (314) 567-5552.

Project CHOICES (Children Have Opportunities in Inclusive Community Environments and Schools) Summer Institute: Kids: Our Future. July 21-22, Crowne Plaza Hotel, Springfield, IL. Registration fee: $75 per person (fee waived for parents of children with disabilities). For additional information contact Project CHOICES, 6S331 Cornwall Road, Naperville, IL 60540. (630) 778-4508, Fax: (630) 778-1791, E-mail: ECHOICES@aol.com or register via web site: http://www.projectchoices.org

|

moonlight is the newsletter of the Riverbend Down Syndrome Association. It is made possible by the William M. BeDell Achievement and Resource Center, 400 South Main, Wood River, IL 62095, (618) 251-2175.

Editor: Victor Bishop

Web Site: http://www.riverbendds.org/

|

|

|

Project CHOICES provides free on-site technical assistance to school districts to assist them in providing education for children with disabilities ages 3-21 in preschool settings and general education classrooms and is funded by the Illinois State Board of Education.

Linking Families: Connecting Strengths. 2nd Biennial Parent-to-Parent Conference. July 9, 10, & 11. Renaissance Hotel, 9801 Natural Bridge Road, St. Louis, MO. Conference fees: single registration: $35; families: $55; professionals: $100. For more information call the Missouri Planning Council at (800) 500-7878.

Resources

Family Resource Alliance of Madison County is a coalition of agencies and organizations devoted to helping families access the support they need to raise healthy children. Calls to the Family Resource Phone Service at 1 (800) 872-0528 are taken weekdays from 8:30 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. to help families individually access the service they need.

The Hayner Public Library District, serving Alton, Godfrey and Fosterburg, has a Youth Library located at 401 State Street, Alton, phone: 462-0652. Dial-a-Story: 462-TALE.

The Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis Monthly Parent Play Group meets every second Thursday of each month at 211 North Lindbergh from 9:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. For more information call Karen Voda at (314) 645-8939.

College for Kids. Travel to road to adventure! Summer camps and classes: art, computers, science, sports and adventure. For more information contact the Lewis & Clark Community College at 466-3411, ext. 3542 or 3502. To register contact the Enrollment Center at 467-2222.

News Clipping

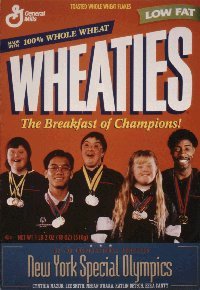

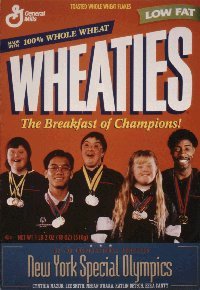

Megan O'Hara, Wheaties Hero. Her success is a triumph of patience, optimism, and love by Peggy O'Hara as told to Anne FitzPatrick. Catholic Digest, March 1999, p. 44-51. E-mail: CDigest@stthomas.edu URL: http://www.CatholicDigest.com. Reprinted from Catholic Digest, 2115 Summit Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55105-1081. © Copyright 1999 by the University of St. Thomas. Reprinted with permission.

OUR BRIGHT, ENERGETIC son was 2 when our second child, Megan, was born — the baby girl we'd hoped for. But our joy soon turned to worry when we learned Megan had been born with Down syndrome as well as other complications.

We knew nothing about Down syndrome, and the information we were given at the hospital was not encouraging. "She'll probably never walk," they said. "It's doubtful she'll ever develop understandable speech. You may be able to manage for a couple of years, but you'll eventually have to place her in an institution." "We'll never do that," I shouted, startling the doctor. More quietly, my husband, Chuck, agreed. "God gave her to us," he said, "and God will provide for our needs — and hers." Since then, Chuck has repeated these words many times, and they have never failed to comfort and reassure us.

Despite the medical advice we were given, which was not uncommon in the '70s, we vowed it would be different for our Megan. We read everything we could find about Down syndrome and found other parents with whom to compare notes. Though not all we learned was positive, we forced ourselves to remain optimistic. Still, we endured moments of doubt: when Megan struggled through a pulmonary illness, when we paced and prayed during her heart surgery at age 3, when it seemed she would never be toilet trained.

Occasionally, overwhelmed by the time and effort it took to care for Megan, we wondered if our hopes for a large family must be abandoned. How could we take the chance of having another special-needs child?

BUT WE ENJOYED shining, triumphant moments with Megan, too. When, for example, she spoke her first words, "Mommy, Daddy, love," we were overjoyed. And when she took her first wavering steps, we knew our Megan would accomplish more than had been predicted. How much more, though, we never dreamed.

Instead, we searched out every facility and agency in our community that helped parents like us. We arranged for speech and physical therapy, and we enrolled Megan in classes designed for children with special needs. In addition, we found many helpers, people we considered sent by God.

By the time Megan was 5, our third child was on the way. Our doctor suggested genetic studies. "No matter what they show," I told him, "it won't make any difference" Once again, we felt, God was giving us a gift. Then we found I was carrying twins! "Lord, there aren't enough hours in the day now!" I said. "How will we ever manage?"

Chuck's answer, of course, was to trust God, as we had done all along. We promised ourselves that, no matter what, we would not treat Megan differently than our other children. We were confident in the steady progress she had been making; we would encourage her, like anyone else, to be all she could be.

So Matt and Maureen joined our family. Two years later, along came twins Molly and Mark. Not surprisingly, as the days blurred into one another, our prayers became more intense: "Lord, we need help!"

But our prayers were quickly answered through our nearby friends and extended families, all willing to lend a hand. By the time our youngest, Patrick, joined our clan, we were as well-organized as any large family could be. Despite a shortage of time — we always wished for more — we had plenty of love to go around, and that was what counted.

IN ADDITION TO being an especially loving child, Megan did well in her special class and showed an aptitude for athletics in gym class. "I'm good at sports," she told us proudly. "I'm going to Special Olympics some day."

"Well, maybe," I responded. I didn't want to burst her bubble or, on the other hand, raise her hopes too much, either. "You'll have to work very hard."

|

|

Wheaties box cover courtesy of General Mills. Used with permission.

|

"I do," she said. "I do work hard." So we learned about the Special Olympics and added our dream to Megan's. We went to practice sessions and encouraged her as she trained with other Down syndrome children. Still, we were not prepared for the first sport she chose: speed skating. Even using a walker, which was allowed, it promised to be difficult. Nor were we prepared for her decision to go to the winter games without us. "But we want to be there," Chuck and I told her, "to cheer you on"

But Megan was firm. "It's my vacation," she insisted. "Just me and my friends."

When the bus pulled away we could only wave, holding on to the reassurances from other parents and the chaperones. "The first time is the hardest," one of the parents said. "She'll be fine." Nevertheless, our weekend was consumed with worry. "Dear God," we prayed, "don't let Megan get sick. And help her not to be disappointed."

"I just wish we were there," I said to Chuck. "She might need us. She's never been away before."

"Peggy," he replied patiently, "we've worked hard to make her independent. Now that she's testing that independence, we have to learn to let go."

I knew, of course, that he was right. Still, I couldn't resist saying, "Easy to say, hard to do"

I WAS ON pins and needles as we waited for the bus to return on a Sunday afternoon. The day was cold, with snow on the ground, but the sun was bright. Megan's expression as she ran toward us was shining, too. Her smile told it all — her weekend had been a success. She unzipped her heavy jacket to show us a bronze medal on a red, white, and blue ribbon around her neck. "Look, Mom! Look, Daddy!" she cried. "I won! I won!"

Chuck and I enfolded her in a big hug. "Oh, honey, we're so proud of you!" Similar scenes were taking place all around us. We knew we had become part of something big, something wonderful.

Since then, Megan has participated in winter games, summer games, at home and away. Eventually, too, she accepted our attendance, though she's kept her distance and made it clear she is with her friends, not us. Just the same, we cheer loudly and marvel at the way she handles herself.

Now, at age 23, Megan has acquired more gold, silver, and bronze medals than we can count, in all kinds of events: swimming, where she's especially proficient, track and field, softball, bowling.

Still, for all her success, a recent long-distance phone call came as a total surprise. "Megan," I told her after I'd hung up, "they want to put your picture on the Wheaties box!" She looked blank for a moment. "You know," I said, " 'The Breakfast of Champions'? They're going to have pictures of five Special Olympics' athletes on the box. You'll have to go to Rochester to have your picture taken with the others." "Oh," she said. "OK." Typical Megan! She takes everything in stride. When the rest of the family heard the news, though, she couldn't help but get caught up in the excitement, overwhelmed with hugs and congratulations.

"I bet you never thought we would have a celebrity among us O'Hara's," one son said.

We never did pray for celebrity. We prayed only for Megan to be self-reliant, healthy, and happy. God answered our prayers in incredible abundance, and we're grateful for that every day.

MEGAN HAS A JOB in the kitchen of a health and rehabilitation center, where she's a good and steady worker. But much of her free time, after the special edition Wheaties box hit the stores, has been spent speaking in schools and at various events. As she tells of her hard work, she's also quick to point out in her low-key way that "anybody can do it." So much for dire predictions that she'd never walk or talk.

"Some kids used to say I was different. A retard," Megan tells audiences, recalling some taunts of the past. "But I'm not a retard, am I?" More than a question, however, her words are a statement of faith in herself and in God, whom she knows to be with her at all times.

Remarkably, none of this has gone to Megan's head. She remains the same placid, hardworking person she has always been, ready to try a different sport, a new challenge.

Watching so many people line up for Megan's signature on their Wheaties boxes. I'm often moved to tears. Chuck, meanwhile, shakes his head in wonder. "Who'd have thought," we say to each other, "that we'd one day be watching our Megan sign autographs?"

Sometimes, people praise us for the wonderful job we've done with Megan. But we didn't do anything on our own. Our other children have always encouraged her, our extended families have always been there for us, and so many professionals did so much for us over the years.

But, above all, we see God's constant presence, fulfilling that initial promise, I have given you this child, and I will provide. Indeed, God has provided, beyond our wildest dreams.

Does Inclusion Work? By Caroline Grimaldi. E-mail: SANTA5967@aol.com © Copyright 1998 Caroline Grimaldi. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

|

|

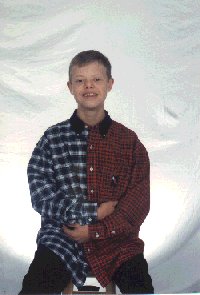

Michael Grimaldi

|

Back in 1991 inclusion was a novel and somewhat 'risky' approach to educating children with disabilities. Since the experts insisted that our son, Michael, needed 'special education' in preschool, we concurrently enrolled him in various special education programs and a typical "Montessori" program (which he attended part-time from the time he was 18 months old). We had a number of horrific experiences with the special-education programs and constantly contrasted them with Michael's contentment and progress in the 'typical' school. When the time came for kindergarten, we made the decision to include Michael in our local school instead of a self-contained special education class. Since this was the first time a child with Down syndrome was included in our area school, Michael received a great deal of wonderful local publicity.

As the years rolled on, and the gap widened between Michael's social/academic abilities with those of his 'typical' peers, inclusion became more challenging. We had moments when we feared we were limiting Michael's academic instruction and potential social relationships with children at his developmental level by keeping him included. We struggled through some difficult moments but our 'gut' kept telling us that inclusion was still the answer. The Director of Pupil Personnel Services had been consistent through all these years in attesting that, "Michael belongs in the Croton schools".

Michael entered 6th grade at the Pierre Van Cortlandt Middle School this past September, which brought a whole new array of challenges. The elementary school staff of past years had grown with Michael and everyone there was comfortable with his presence. We now had a whole new group of teachers to 'convince' that Michael needed to move on with his classmates — that the middle school is just an extension of the inclusion that had been successful for the past 6 years. After several meetings with Michael's new teachers, I admit that I had wavered and considered another educational environment. However, Michael consistently held firm to his desire to remain in the local school with his friends.

One day, wavering in another moment of doubt, I found this report in Michael's backpack with a note ascribed by his aide, "thought you would enjoy reading this". It was a class assignment required in the 6th grade English class to write about a person that one admires. Reading this paper resolved any hesitancy I had about inclusion and summarized all the benefits that had taken 7 years to achieve. The author, Alex Haber, said it all. At the time of this writing, Alex was a wonderful 11-year-old who has grown up with Michael because of inclusion. He shared a few 'play dates' with Michael in the early elementary school years and had been in a number of his classes since. Any parent hesitant about inclusion can quickly see the merits that it brings over the years by reading this report. I hope that you are as touched by it as we were.

The Person I Admire by Alex Haber. © Copyright 1997 Alex Haber. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Do you admire anyone? If so, why? I admire someone, and I have a reason why, as well. I admire a boy that is in my class. His name is Michael Grimaldi. He has Down syndrome, and yet, he has achieved a lot in the lifetime he has had so far.

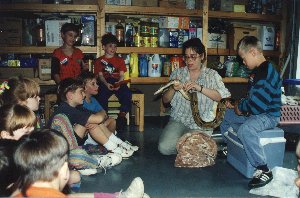

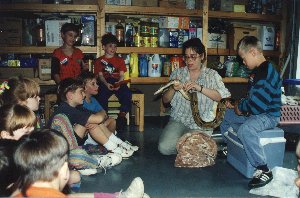

|

|

The author, Alex Haber, sitting on bench with red T-shirt, closest to the "Critter Lady", at Michael Grimaldi's 8th birthday party, who is handling the snake.

|

Michael is not too short, about average height, and has dirty blond or light brown hair. He is very flexible, but not awkward in appearance. He is a boy, very normal, and friendly (most of the time), as well. He is almost always in a good mood and is fun to be with. I also admire him because he was the first child with Down syndrome to ever be in the Croton schools. Above and beyond school, he is an amazing horse rider, and has a wall in his room full of ribbons and medals. Personally, I think that if it wasn't for the Down syndrome, he would be a very, very smart student. He is in all of my academic classes, and I marvel at the fact that during class, he does his own, special, work, and doesn't usually burst out or become annoying. He has always considered me a friend and always calls me Alex Haber. When he is not occupied, and I see him in class, he asks me what I was for Holloween this year. He really likes Holloween and scary things. He also has a very wide vocabulary.

One incident that I remember between Michael and I was the first time I went in his room. The second I walked in, on the wall opposite me, I saw ribbons. Horse ribbons. Not just a couple, though. At least ten! There were also articles cut out of the newspaper from when he was in kindergarten about how it was amazing and he was the first boy with Down syndrome in the Croton Schools, it made me think that this child was amazing, achieving so much that I couldn't, yet still having all the needs he does.

Even though I know that this is impossible, I have a wish for Michael. I wish that Michael's Down syndrome would go away. Just disappear. I wish this because I know that if Michael was not limited by his Down syndrome, he could achieve even more and be even more amazing than he is now. He would probably be on the ACE list, if he is not already, and might do much better in life than he will with Down syndrome. He is already a bright kid, but I think he would be even brighter without the Down syndrome. Maybe he'd even win a Nobel prize!

In conclusion, I just want to say that Michael is really just a normal kid. I don't think that he should be treated with any more disrespect than everyone else is. Luckily, from what I've seen, the other kids in our grade do respect him. In fact, I think that they understand him even better than the teachers do.

15-year-old with Down syndrome graduates with honors by Yvonne Condes, Belleville News-Democrat, June 13, 1999, page 1A - 3A.

When Charlotte was born 15 years ago. doctors advised Debbie Goodman to put her firstborn into an institution and tell everyone she had died.

Debbie and her husband, John, knew little about Down syndrome, but knew they couldn't do that.

"Our opinion was. 'She's just a baby. How can it be so bad?'" Debbie Goodman said from their Caseyville home. It wasn't bad at all. she said. "Having a child with disabilities, you're told to throw your dreams away." Debbie Goodman said. "Almost all our dreams for Charlotte have come true."

|

|

Charlotte: Got award.

|

Charlotte, 15, is an honor student at Edward A. Fulton Junior High in O'Fallon. At graduation two weeks ago, she was awarded the Robert Barra Award for Exceptional Personal Development and received that award with a standing ovation, Principal Allen Scharf said.

"This year's recipient sets an excellent example for other students with her determination and dedication. not only academically, but socially as well," according to the speech read at graduation. "I worked very hard." Charlotte said. "I do my best."

Debbie Goodman attributes Charlotte's success to inclusion, Charlotte went to class with other children at Fulton Junior High, with only one special education class.

Kids with Down syndrome can do well. said Dr. Michael Noetzel, associate professor of pediatric neurology at Washington University in St. Louis.

They have a lower IQ than the general population, but they have many other strengths and potential, Noetzel said.

Down syndrome is a congenital disorder caused by having an extra chromosome.

"I have one extra thing in my body," Charlotte said.

"It was a fluke of nature," Debbie Goodman added.

With Charlotte's form of Down syndrome comes a mild form of mental retardation. Her mother asks herself why Charlotte does so well, better than most would think.

"Maybe it's because I love her and think she's wonderful," Debbie Goodman said.

And capable of doing work along with regular education students, she said.

Studies show Down syndrome children who are included in regular education classes develop better than those who are segregated, Noetzel said.

"They have to communicate with kids their age, and they can't rely on morn or dad or their teacher," he said.

Debbie Goodman made sure that Charlotte was included in regular classes. She learned early on what Charlotte's rights were.

When Charlotte was 6, Goodman entered a yearlong program to help parents of children with disabilities, called Partners in Policymaking.

Today, she is an advocate for the Center for Independent Living in Alton. She made sure Charlotte got to do the same things as other kids. That wasn't a problem at Fulton, she said.

Charlotte sings in the chorus and earned money for the eighth-grade trip to Washington, D.C.

She loves music and singing along with her Karaoke machine. Her favorite song is the Olivia Newton-John and John Travolta duet, "You're the One That I Want." "Grease" is just one of the 300 compact discs she's collected.

When she's not off doing activities, she's at home with her brother, Nic, 12, and sister, Ruth, 10.

"I think I'm, like, proud of her." Nic said, of Charlotte winning her award.

What's the best thing of having a sister with Down syndrome? Debbie Goodman asked Nic and Ruth.

"She's never on the phone and I can use it," Ruth said.

Father's Journal

Independence Day

Later that evening, at the fireworks, I would recall the conversation at the community swimming pool: the anniversary of receiving the remains of his son from Vietnam.

I hugged Emmanuel that early morning in the pool; the father mentions he remembers his son daily. I would not know what to do without Emmanuel in my life and handed my son to the father, who kissed Emmanuel's forehead in silence.

|

|

Nic said, "She probably won't bug me as much."

When Charlotte graduates from O'Fallon High School, she wants to become "an advocate for my people's rights," she said.

A conference in Springfield this summer might help her with that. Charlotte will go to the Youth Leadership Summit in July, where Illinois students ages 16 to 21 will learn what their rights are and how to live independently.

It will be Charlotte's first time away from home without her family. When Charlotte graduated from eighth grade, her mother went back and looked at the book on children with Down syndrome she got when Charlotte was a baby.

She looked back at all the things she was told at Charlotte's birth; that she may not walk or live long.

Charlotte proved them all wrong.

"It's not a bad life," Debbie Goodman said. "It's just a different life."