Disability Solutions

January/February, 1999 Volume 3, Issue 3, p. 1, 3-9.

© 1999 Creating Solutions

14535 Westlake Drive, Suite A-2

Lake Oswego, OR 97035

(503) 443-2258

Fax: (503) 443-4211

|

Joan E. Medlen, R.D.

Disability Solutions January/February, 1999 Volume 3, Issue 3, p. 1, 3-9. |

Printed with the permission of Joan E. Medlen, R.D., Editor © 1999 Creating Solutions 14535 Westlake Drive, Suite A-2 Lake Oswego, OR 97035 (503) 443-2258 Fax: (503) 443-4211 |

In the years since my son was born with Down syndrome, my work as a dietitian has changed. At times I look back at struggles we encountered (medically and educationally) and realize that there was information available I would have found useful during stressful times. Hindsight is like that. The main article in this issue of Disability Solutions is the result of one of those situations.

More often than not, children with Down syndrome take longer to pass through all the different food textures than other children. Usually, from a "clinician's" point of view, it is not "problematic." Yet from where I sat as "Mother," it sure felt problematic! The article, From Milk to Table Foods: A Parent's Guide to Introducing Food Textures includes specific information regarding the process of learning to chew foods and how to tell when it is time to begin to introduce new textures to your child with Down syndrome based on ability, not age. There are also tips to help teach your child how to chew and some suggestions for problem-solving common rough spots.

If after reading this article, you are wondering if you should seek the help of a feeding team, here are some questions to consider:

If you answered yes to two or more of these, I highly recommend you seek out a feeding team in your community. Feeding teams consist of a multidisciplinary team dedicated to solving concerns about eating and feeding. They are usually associated with the children's hospital in the area.

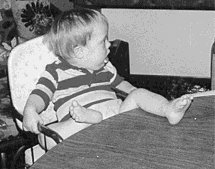

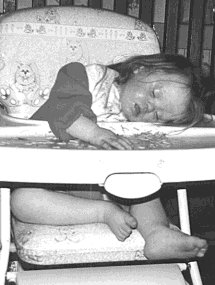

Last, this article would not be complete without pictures of many young children with Down syndrome learning about food. Thank you to all the parents who shared pictures of their children with us. Unfortunately, we could only include a few (though I got to enjoy all of them). The children in the article are:

Stefanie Ward (now 16), Virginia Beach, VA.

Andy Medlen (now 10), Portland, OR.

Mackenzie Bockwoldt (now 5), Frankfort, IL.

Avi Leshin (now 5), Corpus Christi, TX.

Bridgett Richards (now 7), Troy, MI.

Madison Duffey (now 5), Philadelphia, PA.

Stefanie Ward (now 16), Virginia Beach, VA.

Learning to eat foods, from the first bites of baby cereal to regular table foods, is a long process. For children with Down syndrome, learning to coordinate tongue and mouth movements from the first bites of baby cereal to eating table foods takes longer and can cause parents concern. It helps to understand the developmental stages and skills children must go through learning to chew. This article discusses what chewing skills to look for before changing the texture of food and how to encourage and teach your child with Down syndrome to chew different foods. With this information you can sit back and enjoy the fun and messiness of discovering foods together with your child.

There is little information available to parents explaining what to look for when introducing new food textures to children with Down syndrome. Most information is written for children without disabilities and presents the introduction of different food textures as an age-related table. The ages for different types of foods (strained baby food, pureed, ground, chopped foods) reflect the typical age that certain tongue and jaw movements develop. Some children with Down syndrome will follow these tables and have little trouble with the introduction of foods, or chewing. Others will experience delays because of lower muscle tone or a smaller mouth cavity. Understanding chewing development and the key tongue and jaw movements that signal readiness for a new food texture - such as going from strained, pureed foods to thickened, pureed foods - is essential to the process (table 1).

Before your baby is offered her first bite from a spoon, she is getting her food through breast-feeding or from a bottle. The mechanism for swallowing during that time is called suckling, which is a combination of extension and retraction of the tongue, forward and backward jaw movements, and a loose closure, or connection, of the lips around the nipple.

Throughout those first months of breast or bottle feeding, your baby builds strength in her tongue and mouth and a new pattern begins to emerge which is called sucking. Sucking includes a more rhythmic up and down jaw movement, an elevation of the tip of the tongue, and a firm closure of the lips around the nipple, which creates a negative pressure in your baby's mouth. It is usually shortly after this sucking period begins that the first bites of baby food are introduced, commonly between four and six months of age.

That first bite of baby cereal is a big event for everyone involved. Not only is it a new developmental stage,

but it is a change in the relationship between your

baby and everyone around her. Eating requires more

participation and interaction from her. Those who feed

her will learn to listen to her cues regarding how fast

or slow to present each bite. In these early interactions

the groundwork is laid for other give-and-take situations. It is a natural time for parent and child to develop an awareness of overall body tone, stamina, and

to develop a feeling of mutual trust and respect.

Those first bites of baby cereal are also very messy.

Generally babies will lose a certain amount of the cereal

as they try to coordinate their tongue and jaw movements to this new, foreign food. Babies with Down

syndrome often lose more food than those without

Down syndrome with these first bites. If too much

food is lost, your baby's jaw movements may still be

more of a suckling pattern-tongue and jaw thrusts resulting in loss of food-than a sucking pattern. A good

rule of thumb to use is if your baby with Down syndrome seems to be losing 75% or more of the food

from each bite, it might be best to wait a few days and

try a bite of cereal again. Once she is eating baby cereal

successfully, follow the typical pattern for introducing

first baby foods. This category of foods is called

strained, pureed foods which includes baby cereals;

jarred, strained baby foods; and homemade, pureed,

strained foods.

Those first bites of baby cereal are also very messy.

Generally babies will lose a certain amount of the cereal

as they try to coordinate their tongue and jaw movements to this new, foreign food. Babies with Down

syndrome often lose more food than those without

Down syndrome with these first bites. If too much

food is lost, your baby's jaw movements may still be

more of a suckling pattern-tongue and jaw thrusts resulting in loss of food-than a sucking pattern. A good

rule of thumb to use is if your baby with Down syndrome seems to be losing 75% or more of the food

from each bite, it might be best to wait a few days and

try a bite of cereal again. Once she is eating baby cereal

successfully, follow the typical pattern for introducing

first baby foods. This category of foods is called

strained, pureed foods which includes baby cereals;

jarred, strained baby foods; and homemade, pureed,

strained foods.

If your baby continues to lose a lot of food with each bite due to jaw and tongue thrusts, there are some things you can do to help her learn to control her mouth and tongue while eating:

| Food Type | Pre-Food | Puree | Thick Puree | Ground | Chopped Foods | Table Food |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chewing Stages | Suckling | Sucking | Strong Sucking, Early Munching | Munching | Chew progresses to a mature rotary chew | Well-practiced at mature rotary chew |

| Feeding Skills to Note | Rooting | Attempts to hold bottle. Decrease in gag reflex. | Shows interest in "guiding" spoon. | Decrease in gag reflex. Increased use of cup. Grasps spoon and "plays" with it. | Assists with feeding and drinking with increasing independence | Messy self feeder, switching back-and-forth between utensils and fingers. |

| Types of Food to Offer | Breast milk or formula | Infant cereals should resemble a "Heavy Thick Liquid" or Applesauce. Other foods include blended, strained, baby foods (jar or homemade) |

Gradually increase the thickness of pureed foods with baby cereal, wheat germ, or potato flakes. Provide opportunities for chewing using teething type foods (pretzels, toast and so on) |

Mashed, cooked vegetables, scrambled egg, mashed soft-boiled egg, cottage cheese. | Chop regular table foods in small, fine pieces. Introduce finger foods that are easily chewed. | Monitor easy-choke foods (see table 2) for safety. Modify list as appropriate. Introduce crunchy and chewy foods to build jaw strength. |

| Indications for the Next Step | The beginning of a sucking motion. | Strong, well-developed sucking motion. | Emergence of up-and-down chewing motions. | Side-to-side movement of foods with tongue. | Individualize for preferences and abilities. | |

| Precautions | Heed choking precautions | Do not mix textures (such as spaghetti with meat balls, peas in mashed potatoes) | Avoid easy-choke foods (see table 2) |

Give yourself and your baby some time together at this stage. It takes practice to develop a rhythm you are both comfortable with.

Some children will have tongue thrusting movements and continue to lose food as they eat. If she is eating her foods without coughing or gagging, then she has most likely found a way to adapt her tongue movements. If she is coughing, gasping, gulping, or gagging after most bites of food, check with your doctor or speech pathologist to make sure she is swallowing safely. As your baby gets accustomed to strained, pureed foods, she will begin to develop a strong sucking action.

Once your baby is proficient with strained, pureed foods, which you can tell by the stronger sucking action, it is time to begin thickening her foods. While eating these thickened, pureed foods your child learns to use her tongue to move food in her mouth. To thicken foods, add instant potato flakes, wheat germ, bread crumbs, or dry baby cereals. Using wheat germ to thicken foods is also an excellent way to increase fiber. When you thicken strained, pureed foods, there are a few things to remember:

During this stage (thickened, pureed foods), your child will develop what is called a phasic bite reflex which is a rhythmic bite and release pattern that looks like she is opening and closing her mouth when something touches her gums (a toy, a spoon, some baby food, or your finger). This is a good time to let her explore with a spoon or an empty cup. Although this stage does not signal time to change your child's food texture, it is an important step to being able to accept different textures. Allowing her to chew on things such as wash cloths and toothbrushes help her get used to the feeling of different textures in her mouth. This is helpful later when she is trying out new and different foods.

The next chewing stage to look for is munching, which is when your child moves food in her mouth by flattening and spreading her tongue while moving her jaw up and down. For some children with Down syndrome, this may look something like a flattening on the roof of the mouth followed by a pushing outward of the tongue to move the food as she opens her mouth.

When you see she is beginning to munch, it is time to introduce some finely ground foods, such as cooked, mashed vegetables, scrambled eggs, or cottage cheese. This is your child's first experience with texture in her food. She may be surprised or react strongly. Be prepared for a lot of messes. If she rejects a food (throws it, spits it out, smears it all over), don't take it personally. Offer a small amount again in a few days. Eventually the food will make it to her mouth.

It is not uncommon for children with Down syndrome to continue to struggle with low oral motor tone at this stage. Some children may find ways to

move foods with their tongue that is slightly different

from what is considered "typical." Again, if your child

is choking, gasping, or gagging a lot, ask for help from

your doctor or speech pathologist. If, however, she is

handling foods without choking or gagging, but is

having trouble coordinating her chewing or tongue,

here are some things you can do to help encourage

her eating skills:

|

Table 2 Foods to Watch Some foods require caution for any child who is still learning to handle foods in her mouth. Children with Down syndrome often need to be cautions with these foods until age 5 or beyond. If your child has not yet mastered a "mature rotary chew," only offer these foods with strict, attentive supervision (or not at all).

|

When your child is able to move foods from side-to-side with her tongue, it is time to introduce finely chopped foods. Use foods from the family meal that you chop very small. It's best to begin with foods that are easy to chew, such as chopped pasta, cooked vegetables, cooked potatoes (without the skin), or canned or very ripe fruits. Let her watch you remove her food from serving dishes so she sees it is the same as what the rest of the family is eating. This usually makes these new foods particularly interesting to experiment with and eventually eat. As she becomes comfortable with finely chopped foods, gradually increase the size of her foods to bite-sized pieces.

During this time, your child will slowly work toward a mature rotary chew, which uses the tongue to move food from side-to-side in the mouth along with a coordinated movement of the jaw in vertical, lateral (side-to-side) and diagonal movements. A mature rotary chew looks like a smooth, circular motion while the jaw opens and closes to chew. For many children, with and without Down syndrome, this is easy to observe because it is difficult to do with their lips together, eliciting the familiar comment, "chew with your mouth closed!"

For children with Down syndrome, it is quite helpful to understand what your child is learning to do as you introduce new food textures. Rather than using age to decide when to introduce a new texture, watch your child eat and look for the skills she needs to progress.

It takes children with Down syndrome longer to chew their food, which continues for many years or may be life long. This could be because of low oral motor tone, motor planning (coordinating the movements to do the chewing), or from general fatigue from the work of eating. Regardless of the reason, it is something to keep in mind at meal times, particularly as you help her learn to eat. It may also be something to consider at day care, preschool, and as your child enters school; she may need more time to eat her lunch and snacks.

Learning to eat foods and progress through textures is more than developing chewing and swallowing skills. Though these skills are necessary to successfully eat regular table foods, there are many things that must be considered beyond chewing for your child to be able to eat well, including what goes on during the family meal. As with most things, there will be times of frustration along with joy in accomplishments. Sometimes, in the middle of the frustrations we feel from day-to-day living, it is hard to remain positive. When you are feeling frustrated, here are some things to remember that may be helpful:

There are times when despite your best effort, or because of medical complications, your child with Down syndrome may not be moving from baby cereal to table foods in the way you expected. Early Intervention Team members are available for you to ask questions about feeding your child. Each team usually has a speech pathologist, and an occupational therapist, and some will have dietitians who all are familiar with feeding concerns. In some cases, it may be necessary to consult a group of professionals who specialize in feeding concerns. If you are unsure if you need to consult a feeding team, ask your pediatrician or call a hospital that specializes in treating children. Ask to speak to a pediatric dietitian or the feeding team.

Learning to eat is a delightful time for parents and children. It's a time full of new experiences and creative ways to explore foods, utensils, and the reactions of others. Understanding when and why to introduce new foods to children with Down syndrome makes it possible to move forward while you relax and enjoy the messes together.

Thanks to Jane Grosfield, M.A., CCC-SLP and Julia Borgreen, M.A., CCC-SLP of the Scottish Rites Center in Great Falls, MT, for review- ing the manuscript.